It was an eventful early morning as we had late notification that the Borrowdale road from Keswick was closed. I made an extra-early start from home and took the narrow and very winding route via Buttermere. Reaching Newlands Hause, I found the first few metres of the descent into Buttermere valley was very icy, with what looked like a covering of snow on the road, but beyond that it was fine and I made the descent safely. Arriving at the Seatoller National Trust car park I found that the road was not in fact closed, and most people had arrived via Borrowdale, which was probably just as well. We walked a short distance down the Seathwaite road, crossing the bridge and immediately taking a gate into the woodland. As the woods have been quite extensively surveyed, we decided not to do a full species list, but just check the species noted in Ben Averis’s report, and any additional species of interest. As there were a couple of beginners or near beginners in the group, we started by looking at some common species and explaining some of the basics of bryophyte identification. Andy McLay soon joined us, having been notified that the road closure was a false alarm.

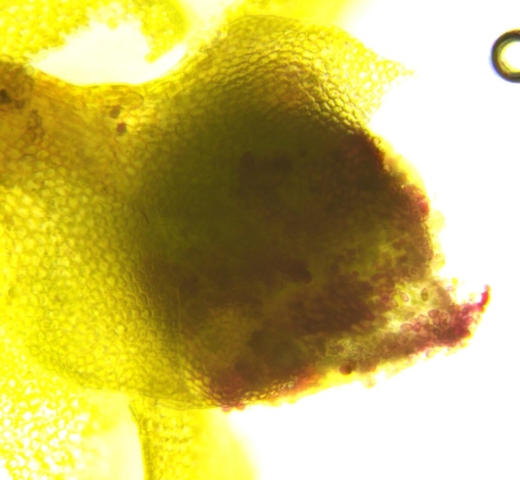

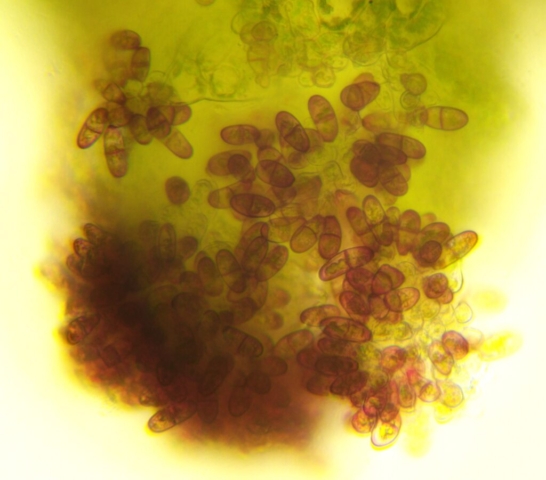

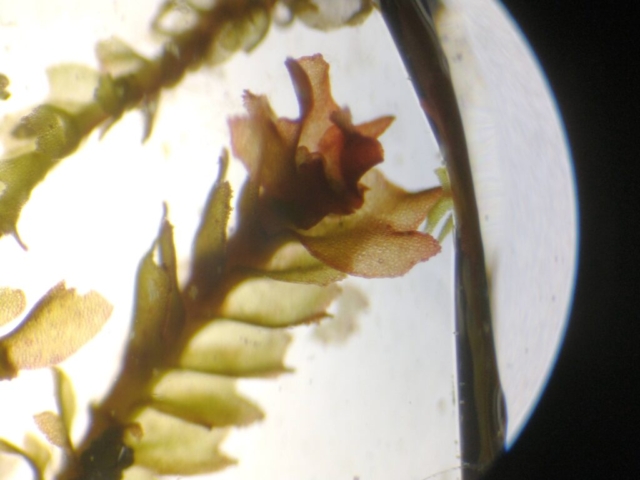

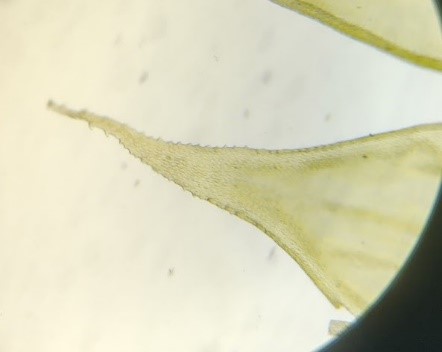

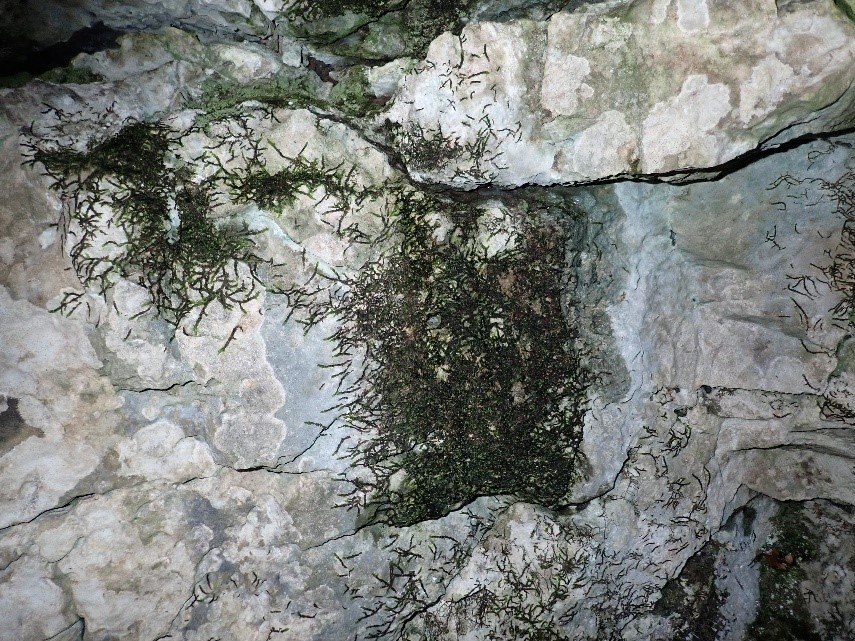

We started by looking at some rock faces near the north edge of the woodland. There was plenty of Saccogyna viticulosa, and a few cushions of Rhabdoweisia crenulata, the teeth at the tip of the leaf just about visible through a hand lens. Lower down the north-facing side of the outcrop there was some Plagiochila spinulosa. Sloping rocks had plenty of Hageniella micans, sometimes more green than the typical golden colour, and this species would prove to be abundant across the north end of the site, despite being nationally quite scarce. We soon found some small patches of Harpanthus scutatus, standing out with its vivid green colour. Bazzania trilobata started to appear on small boulders. One such boulder had some nice Orthocaulis attenuatus, the pale tips of its shoots (with immature pale green gemmae) visible through a mat of Dicranella heteromalla, while nearby there were shoots with more mature red gemmae.

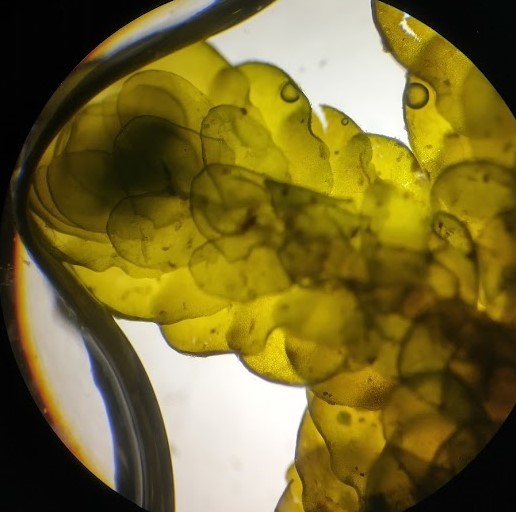

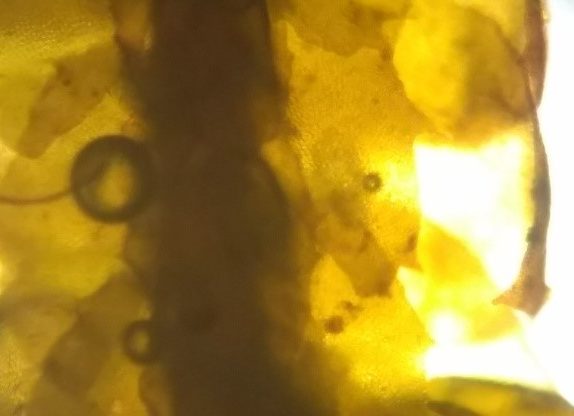

At NY244137 was a large rotting log which proved an excellent habitat for some interesting species, including Dicranodontium denudatum, Scapania umbrosa, Lophozia incisa, Cephalozia curvifolia, and a couple of small patches of Harpanthus scutatus. Andy took a small sample of Cephalozia, which he thought might be C. catenulata (found here by Ben Averis in 2010). Unfortunately he found no fertile material and was unable to confirm this species. We thought we could see tiny red shoot tips through the Cephalozia, and hoped this might be Anastrophyllum hellerianum, but this was perhaps wishful thinking.

We had pinpointed a couple of sites where Adelanthus decipiens had been recorded in 2010, but were unable to refind it. Likely looking boulders were covered in Rhytidiadelphus loreus, and we wondered whether nitrogen enrichment was favouring the growth of this species to the detriment of rarer liverworts. During the lunchbreak near the northwest corner of the woodland, a patch of Anastrepta orcadensis was found on a boulder near the flush heading down to the wall, as well as some Mylia taylorii. Heading south and uphill we followed the wall through some large boulders. Here there was much more Mylia taylorii, forming lovely fat cushions, and quite good-sized, healthy looking patches of Bazzania tricrenata. Reaching the top of the ridge, which was rather dry, we headed south, away from the bend in the wall, down into a bit of a boulder field. Adelanthus decipiens had been recorded on the north face of an outcrop, so we scoured all the outcrops we could find, to no avail. Reaching a flush and beck at around NY243135, we did however find abundant Radula voluta in healthy mats on stones in and around the water. There was also a patch of Pseudohygrohypnum which turned out to be the rarer species, P. subeugyrium (confirmed by Tom Blockeel).

Further up the slope, Paul found a nice patch of Odontoschisma denudatum, with its pale gemmiferous tips.

Heading back up the slope towards the west wall, we reached an area of very large boulders and outcrops. Near here Richard found the first patch of Ptilium crista-castrensis, while Paul found a very distinctive patch of Lepidozia Pearsonii, its thin, threadlike shoots looking distinctly different to the commoner Lepidozia reptans. The outcrops had good cushions of Mylia taylorii and more Rhabdoweisia crenulata, as well as several cushions of Plagiochila punctata, but no Adelanthus decipiens and no Herbertus hutchinsiae. We wondered whether the fairly dry conditions, which left many liverworts looking a bit crisped, was making it hard to spot things.

The light was starting to fade as we headed back downhill, and we decided to call it a day as visibility was becoming so poor. We returned towards the northern gate, following the contours below the steeper, rockier sections of the hillside. We passed a lovely, larger patch of Ptilium crista castrensis but didn’t see any new species on the return journey.

It had been a productive day and we’d seen lots of lovely species, some in surprising abundance. We were a little concerned about the species we had failed to re-find, and felt that it would be good to have a return visit to explore the lower section of Low Stile Wood, and perhaps High Stile Wood or the woodland south of Low Stile wood.

Text: Clare Shaw

Photos: Paul Ross