Eight bryologists convened at the Bowder Stone car park, Borrowdale, on a cold mid-January day for the first meeting of 2026. A short walk warmed us up and brought us to the head of Troutdale, a small side valley with dramatic cliffs and densely wooded slopes. Whilst in 2023 CLBG visited Ashness Wood and Moss Mire (NY2618) just to the north, there appeared to be just 16 species previously recorded in NY2617 which covers most of Troutdale, so this is where we concentrated our efforts.

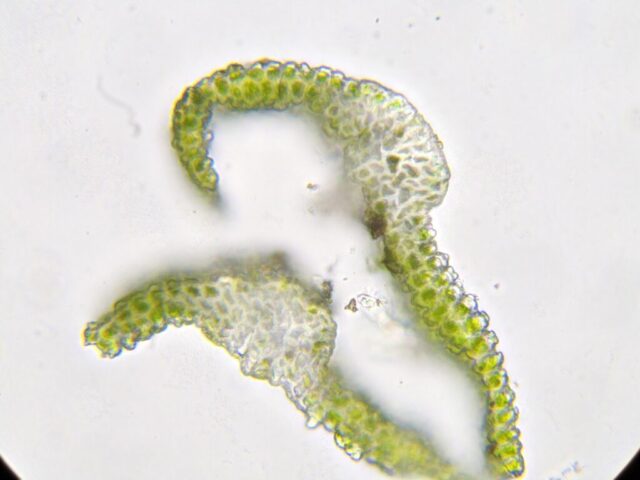

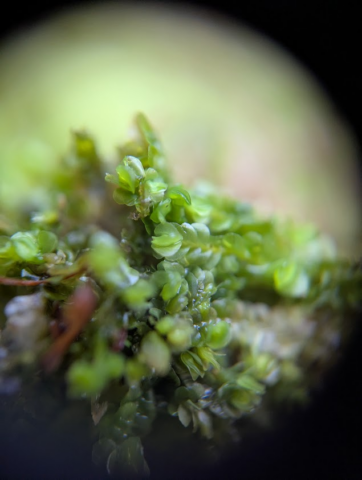

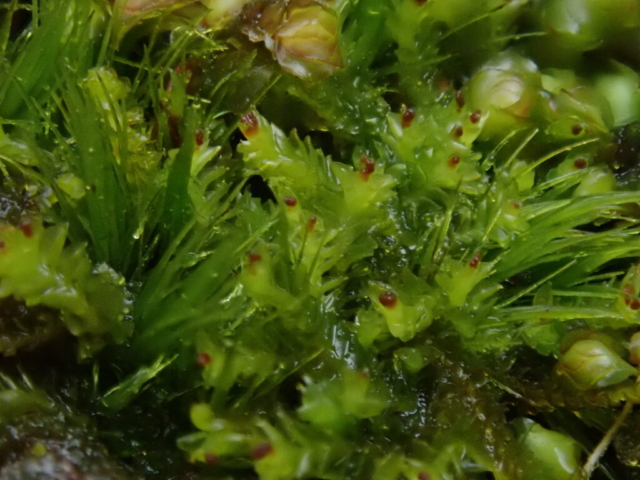

Before we got into the woodland, an open area of mires and flushes produced the first records for the day, a range of sphagna including S. palustre, S. papillosum, S. subnitens, S. rubellum, S. tenellum and S.contortum. Breutelia chrysocoma, Scorpidium scorpioides and Aneura pinguis were also found in this area. From here we spread out into the woodland edges investigating trees and small crags, quickly recording the commoner species. Patches of Bazzania trilobata and Ptilium crista-castrensis here were just the first of many we found during the day. Scapania scandica and Tritomaria exsetiformis were present on trees here and a nice fruiting Rhabdoweisia crispata was found in a rock crevice. Inevitably we gravitated towards the beck, passing rock faces with Amphidium mougeotii, Heterocladium heteropterum and Racomitrium aquaticium. In the beck itself there was plenty of Thamnobryum alopecurum, Hyocomium armoricum, Pseudohygrohypnum eugyrium and several Lejeunea species (L. cavifolium, L. patens and L. lamacerina). At this point, it was decided to focus on the gill and its environs, rather than try to cover the whole monad. After a brief lunch stop, where Neckera crispa and Porella arboris-vitae were found on a base-rich crag, we followed the gill upstream where more Neckera and Ctenidium molluscum were frequent on the rocks. Wilson’s Filmy-fern Hymenophyllum wilsonii was also abundant in places. Excitingly, small amounts of Plagiochila exigua, with its distinctive tiny two-pronged leaves, were also to be found on rocks in the gill, whilst Bazzania tricrenata was discovered at the base of a tree on the gill margin. A curly Dicranum growing on a dead branch with abundant young capsules proved to be D. fuscesens. Lovely brackets of Plagiochila punctata were found on several mature oaks above the gill, and Syzigiella autumnalis was also discovered here. On the woodland floor, Hylocomiastrum umbratum and Loeskeobryum brevirostre were surprisingly common. The steep slopes had a good amount of dead wood with Cephalozia lunulifolia and plentiful Cephalozia curvifolia, and a small patch of Schistochilopsis incisa. An unusual Cephalozia found by Clare was later confirmed as C. leucantha, which was last recorded in Cumbria in 1971 by Jean Paton. One dead stump had a sheet of Odontoschisma denudatum at the base.

Part of the group then continued uphill where a boulderfield was completely covered in bryophytes and large patches of Wilson’s Filmy-fern. Bazzania tricrenata and Mylia taylorii were now abundant, and a small amount of Anastrepta orcadensis was also found. With the light starting to fade, we reluctantly headed back to the car park, stopping off to visit a recently discovered location for Lepidozia cupressina. With 130 species recorded, NY2617 proved to be a very interesting monad, especially as we only visited a small corner of it. Hopefully these records will help Troutdale become part of the Borrowdale Rainforest National Nature Reserve in due course. Thanks to the National Trust for access and allowing us to use Bowder Stone car park.

Report by Kerry Milligan and Clare Shaw

Photos by Kerry Milligan, Clare Shaw, Josie Niemira and Paul Ross