Coenogonium luteum (until recently known as Dimerella lutea) is a striking and usually easily recognisable lichen when fertile. It features on the front cover of the latest edition of Dobson (2018), where it is described as having apothecia that look “like tinned apricots when wet and a poached egg when dry”. Most lichen folk will learn to recognise it early on: so records should reflect its distribution and how it is doing.

The latest maps on the CLBG website (based on BLS records up to August 2024) show 62 records for Cumbria (some will refer to multiple thalli at one location; I can’t be sure that the same lichen hasn’t been recorded on different occasions). Of these, 44 have been since 2020; 16 were between 2010 and 2019 and only two were prior to 2010 (in 2007 and 8). There has been a significant increase in lichen recording in the last few years, and a quick look at C. luteum recording rates against total number of records suggest these haven’t changed much since 2018. So has it just appeared recently? Evidence to back this up might include Francis Rose (1971) not mentioning it his reports from the 1970s, and the Cumbria Biodiversity Data Centre records having just one entry- from 2019.

It’s hard to be sure, but the BLS website maps suggest recent national expansion with far more red (post-2000) hectads than blue (1960-2000), except possibly in south east England. So I think we are OK in saying it is doing well at the moment in Cumbria, and has expanded since the first record- from Grune Point- in 2007. Either that, or it was hugely under-recorded in the past.

As to why: LGBI3 (Cannon et al 2021) says the recent spread is “probably in response to the decline in acidifying air pollution and potentially also warmer temperatures”. But maybe there’s more: Bamforth (2008), writing about the lichens of Lancashire, notes that “whilst C. luteum and its relative C. pineti score 8 and 4 respectively on the Hawksworth and Rose Zone scale meaning it must be very clean and yet both are found at Mereclough, Prestwich, quite close to the council’s refuse destructor.” I personally wonder about the increased rainfall of the last decade or so as a contributory factor.

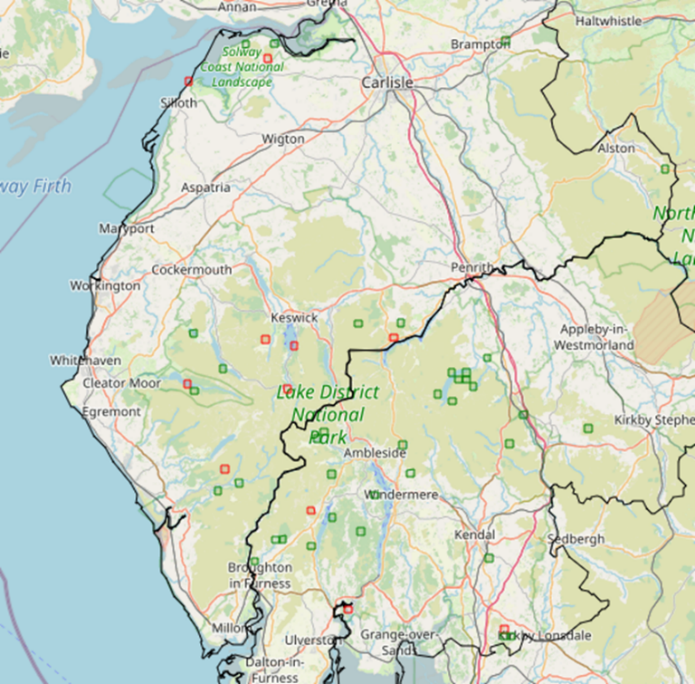

Of our 62 records, 34 are in Westmorland, 28 in Cumberland. As the map shows, much of Cumbria is covered: from Hutton Roof to Grune Point, from Nenthead to Ennerdale. The empty gaps appear to be along the west coast and in the area north of the A66. Is this because it isn’t there, or because these are the areas with least recording?

Dobson says that it is “frequent on bark and moss on deciduous trees in damp, fairly shaded areas of old woodland…where it is sometimes also found on mosses growing on the ground or on siliceous rocks.” LGBI3 says “On bark and associated bryophytes and occasionally on siliceous rocks in humid, shaded situations, and on mosses on soil; locally frequent.”

Of the 62 records, 41 are exclusively corticolous, and only 3 involve growing on stone (not all records have substrate information). Whilst it does grow directly on bark and rock, I would suggest from personal experience that many of those tree records involve it actually growing on bryophytes on the bark.

There are 47 records with a tree species indicated. Oak comes top (10 records) followed by willow (9) and hazel (8). And whilst there is maybe a tendency to grow on more basic-barked trees, there are hardly any more records of it growing on ash or elm (2 of each species) than on pine and spruce (one of each). A Latvian study (Mežaka et al 2008) found it on sycamore, small-leaved lime and birch. Maybe it likes a pH in the middle.

Which is interesting if we think about how Coenognium luteum is often listed (on the BLS spreadsheet for example, or see Woods and Coppins 2012) as an associate of the Lobarion community. In Cumbria, this is probably most often found on basic-barked trees, particularly ash. Also interestingly, there are relatively few records from the strongholds of the Cumbria Lobarion (Borrowdale, for example) and it was not recorded at Rydal Park in 2019.

It is often also mentioned as being in the woodland indices of ecological continuity. It would appear that whilst it used to be in the Revised and New Indices (for example in Coppins and Coppins 2002) it does not feature in their successor, the Southern Oceanic Woodland Index (Sanderson et al 2018). I presume this removal reflects its spread in recent years to woodlands without ecological continuity.

So where does it grow? Well, in a wide variety of places, as there are a lot of damp woodlands in Cumbria. But three particular environments spring to mind, in the first two of which I am coming to almost expect it.

The first is in wet “scrubby” woods, where it can be very frequent on youngish mossy willow (and associated hazels etc). Some examples would be at the back of the Hollingworth and Vose Factory in Kentmere and near Dubbs reservoir above the Troutbeck valley. Similar colonies have been found along the Solway coast in recent years by Russell Gomm and others: here it grows regularly on gorse as well as willow. Whilst some of these woods are densely shaded, others are more open.

A second habitat where I have come to expect to find it is on higher and more isolated trees among the fells: on rowans or other species that are standing out in a heavily grazed landscape, maybe growing from cliffs or in gullies. Examples would be at Wolf Crags, in Far Easdale and on the north side of Langdale. Again, these are not always particularly shaded, though might be north-facing and so avoiding direct sunlight.

A more shaded environment is on older trees among younger planted ones: examples could be in the Dale Park and Claife areas of south Cumbria (on sycamore and oak among conifers), or near Broughton in Furness (oak among planted broad leaves).

Obviously, there are other niches that this lichen is able to thrive in; these three habitats are not exclusive and can blend into one another. But it is perhaps worth thinking about them as we are out lichen hunting. With the increased woodland on the fells due to planting and reduced grazing pressure it may be that these environments will become more common. Will Coenogonium luteum become more common too? Is that what is already happening?

It is perhaps worth mentioning here that I have rarely found it “frequent”; present on more than few trees at a site. It is often a species found once in a wood. Neil Sanderson (2010) described it as being “widespread but never frequent” in the New Forest, and that sounds like a good description to me. But that lack of frequency begs the question why?

At the current rate of recording, we will soon be reaching 100 records for C. luteum in Cumbria. It is moving from being a more notable to a more commonplace species. It is obviously doing well. I would be interested in hearing others’ opinions on it and any other habitats people have noticed it thriving in. Further questions might relate to some of the references I’ve some across. To it being a “mobile species” (how long do thalli last?); to the apothecia being only numerous in winter and spring; to it being “almost always associated to Frullania” ( Lichens Marins). I wonder if these are the case for the species in Cumbria?

Update: It has been pointed out that there are also four records shown on the BLS website interactive maps at a hectad (10km square) level that probably date from before the 2007 find at Grune Point. It is not clear where or when they were recorded.

References

Bamforth ( 2008) Lichens in South Lancashire, https://northwesternnaturalistsunion.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/news-vol11-no1.pdf accessed 18.11.24

British Lichen Society ( 2024) https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/resources/species-accounts/coenogonium-luteum accessed 18.11.24

Cannon, P., Malíček, J., Sanderson, N., Benfield, B., Coppins, B. & Simkin, J. (2021). Ostropales: Coenogoniaceae, including the genus Coenogonium. Revisions of British and Irish Lichens 3: 1-4. Available at: https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/Coenogoniaceae_0.pdf

Coppins, A. & Coppins, B.J. (2002) Indices of Ecological Continuity for woodland epiphytic lichen habitats in the British Isles. British Lichen Society. Available at https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/about-lichens-downloads/indices-ecological-continuity-woodland-epiphytic-lichens.pdf

CLBG (2024) https://cumbrialichensbryophytes.org.uk/lichen-species-maps/#Coenogonium_luteum accessed 18.11.24

Dobson, F.S. ( 2018) Lichens: An illustrated Guide to the British and Irish Species, 7th edition Richmond Publishing

Lichens Marins ( 2024) https://www.lichensmaritimes.org/?task=fiche&lichen=365&lang=en accessed 18.11.24

Mežaka, A. Brūmelis, G. & Alfons Piterāns, A. 2008. The distribution of epiphytic bryophyte and lichen species in relation to phorophyte characters in Latvian natural old-growth broad leaved forests, Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 44: 89–99 (2008) Available at: https://www.academia.edu/75091205/The_distribution_of_epiphytic_bryophyte_and_lichen_species_in_relation_to_phorophyte_characters_in_Latvian_natural_old_growth_broad_leaved_forests

Rose, F, 1971. A survey of the Woodlands of the Lake District and an assessment of their conservation value based upon structure, age of trees and lichen and bryophyte epiphyte flora. Unpublished report to Nature Conservancy

Sanderson, N. A. (2010) Chapter 9 Lichens. In: Biodiversity in the New Forest (ed. A. C. Newton) 84-111. Newbury, Berkshire; Pisces Publications

Sanderson, N.A., Wilkins, T.C., Bosanquet, S.D.S. & Genney, D.R. 2018. Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs. Part 2: Detailed Guidelines for Habitats and Species Groups. Chapter 13 Lichens and associated microfungi. JNCC, Peterborough. Available at: https://hub.jncc.gov.uk/assets/330efebf-9504-4074-b94c-97e9bbdbe746

Woods, R.G. & Coppins, B. J. 2012. A Conservation Evaluation of British Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi. Species Status 13. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. Available at : https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/39f3126a-5558-41e7-8b71-994c27a49541/SpeciesStatus-13-Lichen-LichenicolousFungi-WEB-2012.pdf

Thanks are due to Caz Walker and Chris Cant for their helpful comments and statistical pointers on a first version of this document.

Pete Martin thorncottage@hotmail.com

V2 23.11.24