Bryophytes

A beautiful spring day saw a record turnout for a visit to Brantwood, the home of John Ruskin from 1871 to 1900. The Brantwood Estate covers nearly 90 hectares with a range of different habitats present from lakeshore and garden to oak woodland, gills, mires and upland heath. The general objective of the day was to visit each of these habitats if possible, and generate a decent list of species.

After a general introduction in the orchard, nine bryologists and five enthusiastic estate staff headed into the gardens, leaving the lichenologists examining the apple trees. The short walk from the car park to the Moss Garden produced 38 species, mostly common garden bryophytes but with some good woodland species too such as Dicranum majus and Nowellia curvifolia, plus indicators of base-rich rock and soil, such as Ctenidium molluscum, Neckera complanata and Tortella tortuosa. In the Moss Garden a lush carpet of mostly Rhytidiadelphus loreus under wide spaced oaks produced a stunning visual effect, despite (or perhaps because of) the dominance of one species. Closer inspection revealed several other species here including Tetraphis pellucida on a dead tree stump.

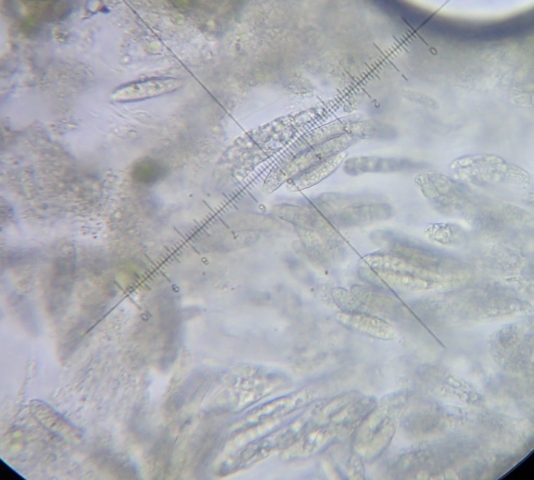

The group then moved swiftly on to Beck Leven, the watercourse which marks the southern boundary of the estate. Oceanic species such as Jubula hutchinsae, Hyocomium armoricum, Plagiochila spinulosa, Platyhypnidium riparoides, and Saccogyna viticulosa were all readily found, together with other more widespread but distinctive mosses of wet places such as Hookeria lucens, Thamnobryum alopecurum and Dichodontium pellucidum. A nice patch of Jamesoniella autumnalis was found on a nearby oak. After lunch, we followed the beck up onto Crag Head, a large intake which includes the highest point on the estate (230m). Fantastic views across Coniston Water to the Old Man and Wetherlam were a temporary distraction until we found the first of a series of mires which produced several sphagna (Sphagnum subnitens, S. capillifolium and S. papillosum) together with Aulocomium palustre and Breutelia chrysocoma. A larger mire with bog pools proved to be more base-rich with Sphagnum contortum, Scorpidium revolvens and S cossonii, and Campylium stellatum. Thuidium delicatulum and Dicranum bonjeanii were also found here.

Descending back through the woods, a small overhanging rockface produced one of the best records for the day, a single patch of Bartramia halleriana with capsules. Our last habitat to visit was the lakeshore. Fontinalis antipyretica was found to be abundant just below the waterline, whilst Cinclidotus fontinalis was frequent on rocks. A small rocky headland gave a last minute boost to the species list with Frullania fragilifolia, Pterogonium gracile, and Trichostomum brachydontium.

At the end of the day, a small group of bryologists and lichenologists reconvened at Brantwood’s Terrace cafe for a much needed cup of tea. A total of 119 bryophytes were recorded on the estate. Many thanks to Brantwood for hosting the visit, and to their staff for their enthusiasm and for making us so welcome.

Kerry Milligan – photos from Kerry Milligan and Clare Shaw

Lichens

A large group including nine lichenologists gathered at Brantwood, 19th century home of John Ruskin, on the east shore of Coniston on a fine spring day. We were joined for a while by estate staff who were keen to find out what lichens and bryophytes they have. There have been no lichen records for Brantwood since 1965 when 42 species were recorded. First stop was the apple orchard, with a dozen small fruit trees grey with bushy lichens and a simple wooden fence equally covered with thalli. Pete gave the group a brief introduction to lichens and found plenty of examples to illustrate the main growth forms. We then recorded as many species as we could, a total of 29 lichens on trees and fence.

What happened next was a new experience for the group – a visit to the cafe for coffee and cake – followed by the more familiar episode of getting absorbed by car park lichens on stone retaining walls including Scytinium teretiusculum. Eventually we tore ourselves away and headed uphill, through the gardens, to the oak woods on the slopes above. Pete was nursing an injured knee so stayed on level ground, talking to the staff and visiting the lake shore where he found Candelaria concolor on ash, along with other lichens.

The oaks above the house looked even-aged as if planted 100-200 years ago, with an understory of hazel, holly and an occasional ash and hawthorn. Most trees had acidic bark, based on the lichen flora we saw, but there was plenty to admire including Parmelia ernstiae, Micarea alabastrites, Arthonia spadicea, Anisomeridium ranunculosporum and a good range of acidic habitat species. The beginners in the group were keen to look at the tiny features on many of the lichens, such as the coarse and fine soredia on Hypotrachyna afrorevoluta and H revoluta.

The boundary wall between wood and field had a good range of crustose lichens including Trapelia coarctata and Opegrapha gyrocarpa, while that on the opposite side of the field had Coenogonium luteum on moss, Baeomyces rufus, Diploschistes scruposus and Psilolechia lucida, amongst others. A birch in the field gave us Graphis elegans and Fuscidea lightfootii and a hazel inside the next strip of woodland was heaving with Normandina pulchella and Thelotrema lepadinum. We looked at crustose aquatic lichens in the beck for a while and kept an eye open for Dermatocarpon luridum having heard a rumour from the bryologists, who’d been there earlier, that itwas spotted but we didn’t see that.

Before heading back towards the car park we visited an oak obviously larger and older than the others – just as well as it had several small patches of Parmeliella triptophylla on the north side of the trunk illustrating the point that oaks can become less acid-barked with age.

Some of the group were lured back to the cafe for a second time before leaving which sets a worrying precedent for future trips…..

Footnote: Pete’s specimens from the lakeshore included one which later turned out to be Normandina acroglypta. So far the total of species seen in all locations stands at about 90 with a few more possible once specimens are examined.

Caz Walker with photos from Judith Allinson, Pete Martin and Chris Cant