Bryophyte report below.

Sub-zero licheneering at Glenamara Park, Patterdale

It was well below zero at the carpark with a thin layer of unmelted snow from a previous day on the frozen ground and a thick coating of frost crystals covering everything– surely it wouldn’t be possible to find anything and, more to the point, could we survive the cold? We set off uphill, fat with many layers of clothing, and warmed up slowly. This strategy of a short walk between trees followed by standing around looking at lichens seemed to work and we stayed out until dusk at 4pm.

Glenamara was originally a deer park, dating from the 16th – 17th centuries and covering about 70 hectares of a north-facing upland valley by Ullswater. The National Trust acquired the site in 2002 and shortly afterwards replaced sheep with a small number of hardy cattle as sheep grazing was completely suppressing tree regeneration. Today there are scattered old birch, alder, oak and ash with some hazel, hawthorn and interesting “wild” apple/crab apple trees (Malus sylvestris), but we saw no sign as yet of new trees coming through.

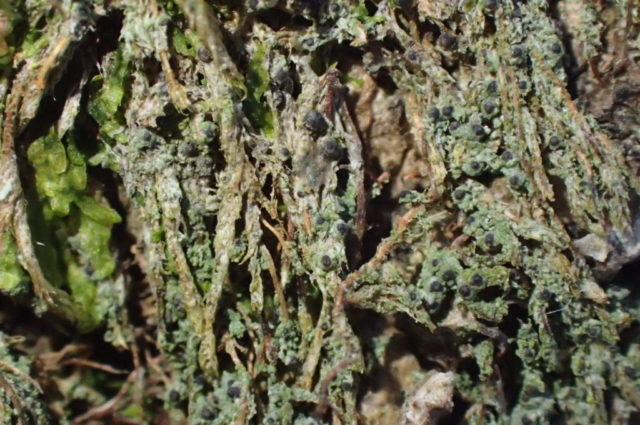

Neil Sanderson surveyed the site for the NT in 2016. He described it as upland pasture woodland and concluded that the only lichen habitat well-represented is that of acid bark communities (Parmelion laevigatae), “due to the past impact of acidifying pollution”, ie acid rain, as well as natural high rainfall acidification (higher than at other sites around Ullswater). He identified only relict base-rich bark (Lobarion pulmonariae) and smooth-bark (Graphidetum scriptae) communities with few species present, as well as small numbers of dry lignum specialists (Calicietum abietinae) – dead wood is well represented at the site.

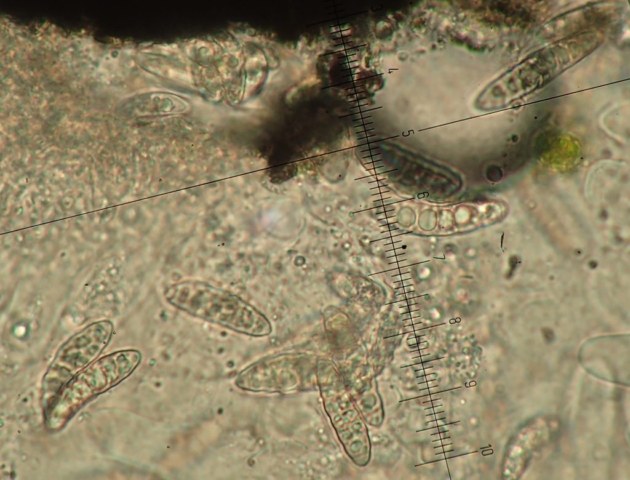

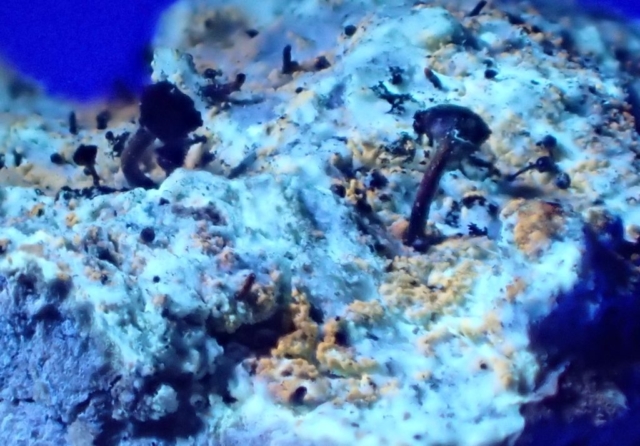

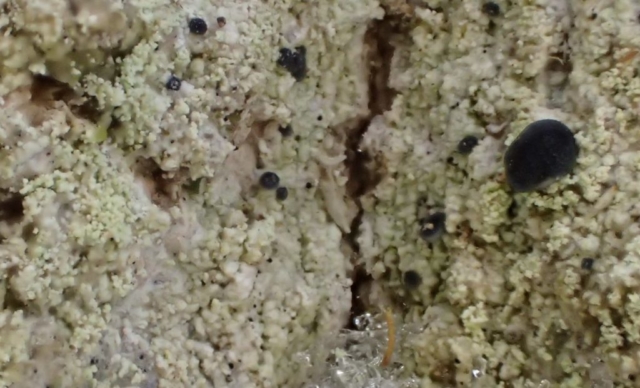

We had a few of Neil’s locations for interesting crustose species but failed to find them – or perhaps we just didn’t recognise them – so we reverted to the tried and tested method of checking out good-looking trees. Old birch had lovely common acidic bark species, like Ochrolechia tartarea and Mycoblastus sanguinarius, as well as Parmeliopsis hyperopta, a tiny grey foliose species with globose clumps of soredia which isn’t often seen in Cumbria (or most of England). Scattered ash trees had Hypotrachyna taylorensis, new to the Ullswater area, as well as Normandina acroglypta and Catillaria nigroclavata. Diminutive Rinodina sophodes was seen on ash twigs and the equally small apothecia of Dimerella pineti on Malus sylvestris.

A mature oak near the boundary wall at the north edge of the site had a good population of pale Ochrolechia subviridis on the trunk, the granular isidia/soredia showing C+red but no apothecia to be seen. Allan Pentecost had showed us this species in 2019 on an oak lower down beside the playing field, fertile with lovely frosted pruinose discs with isidiate margins. Today’s tree also had Bryobilimbia sanguineoatra, with red-brown apothecia becoming convex with age, growing over moss, as well as a streak of buff-coloured Pyrrhospora quernea.

In the end we had a list of 50-60 species, depending on how the specimens work out, but we wandered over only about a quarter of the site. A return visit as usual may be needed once there’s a thaw and the days are longer.

Text: Caz Walker. Photos: Caz Walker, Chris Cant, Belinda Lloyd, Pete Martin

Glenamara Bryophyte Report

Five hardy bryologists ventured into Glenamara’s frosty wood pasture on a beautiful crisp Sunday morning. The site lies entirely within tetrad NY31X, but straddles all four monads. Due to the conditions the group spent the entire day within monad NY3815. Surprisingly for its location, only 7 species appear to have been recorded for the tetrad in the past so there was a lot to do…

Snow obscured much of the ground so we gravitated towards Hag Beck which was still flowing, and most of the records came from here. After ticking off some commoner grassland species, we started to investigate the beck itself.

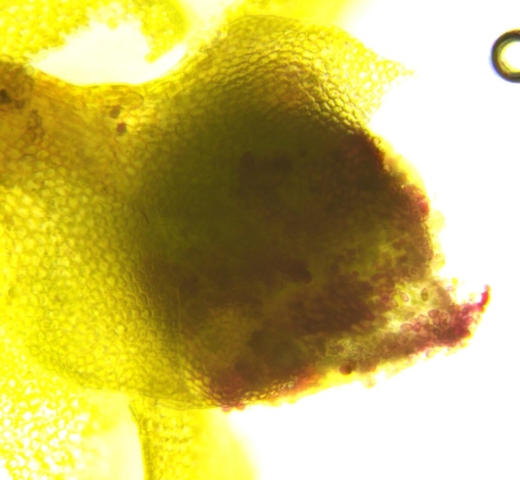

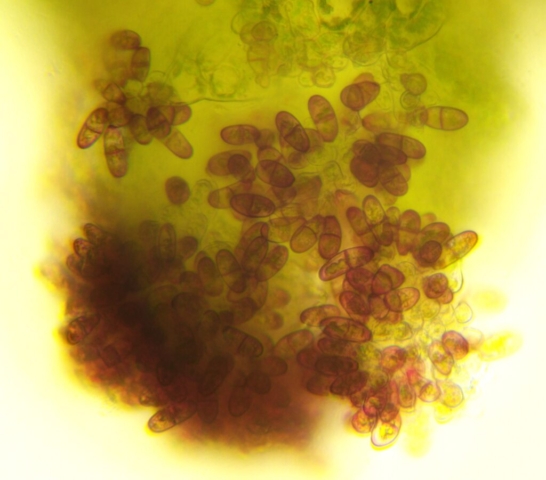

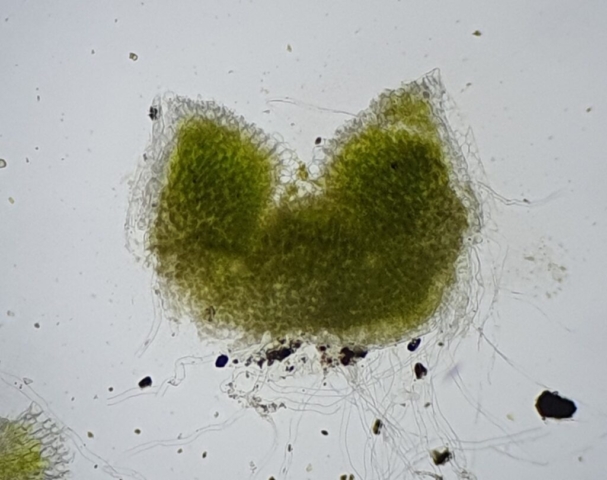

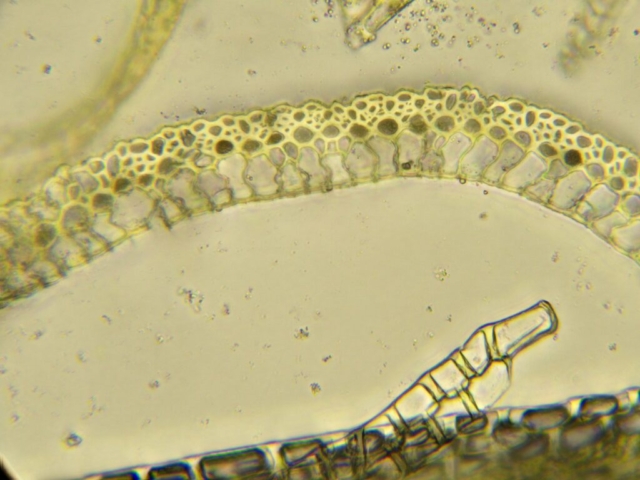

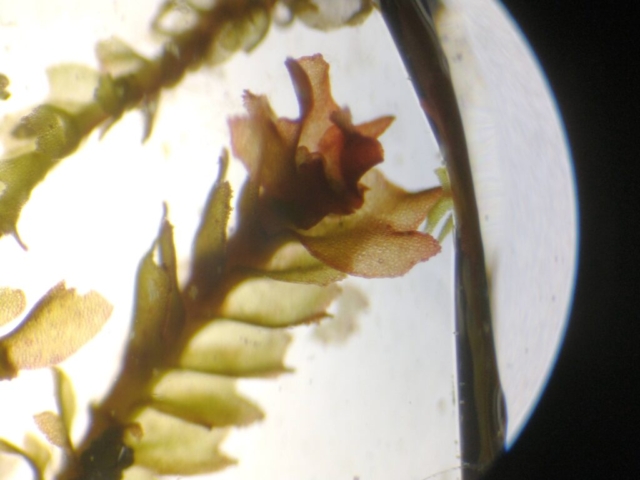

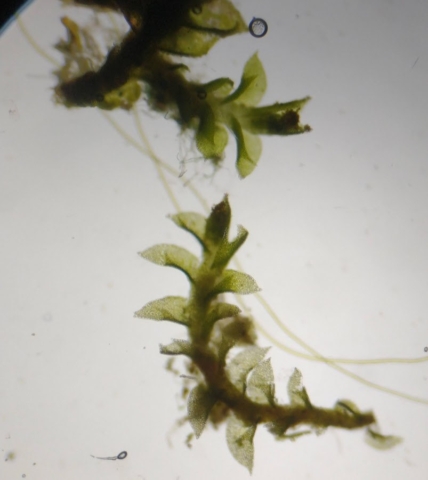

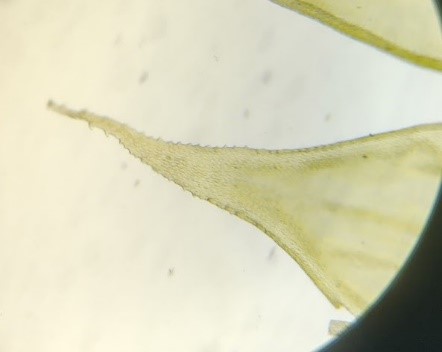

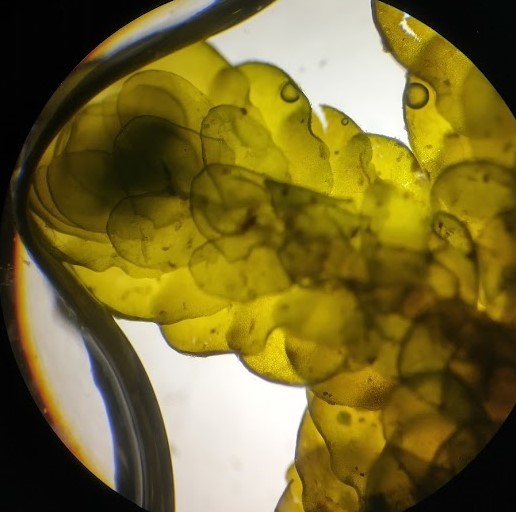

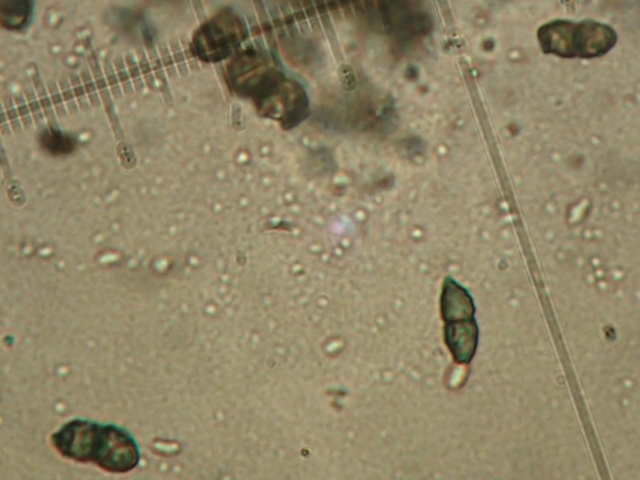

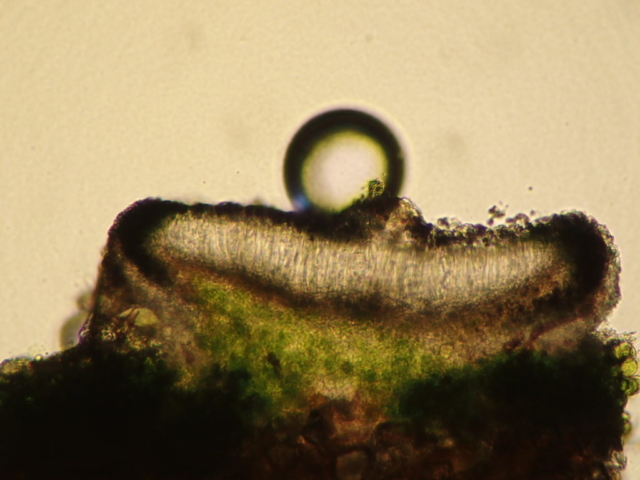

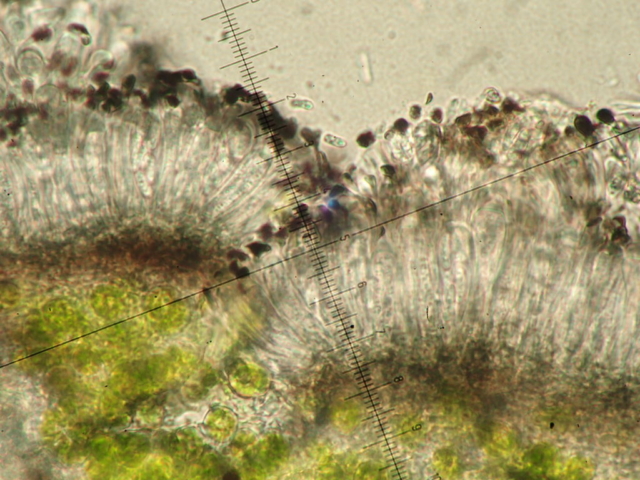

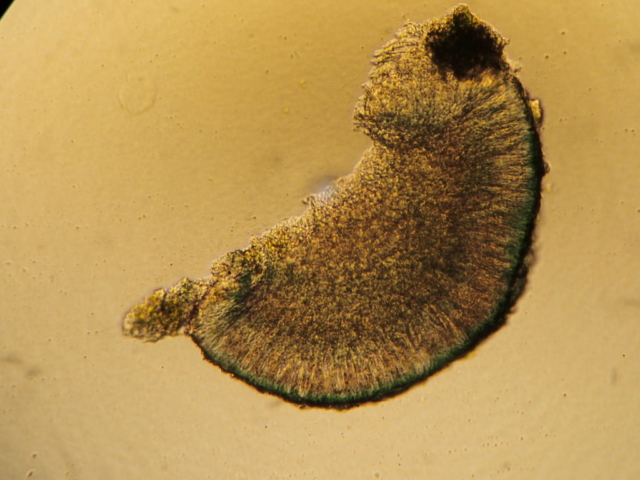

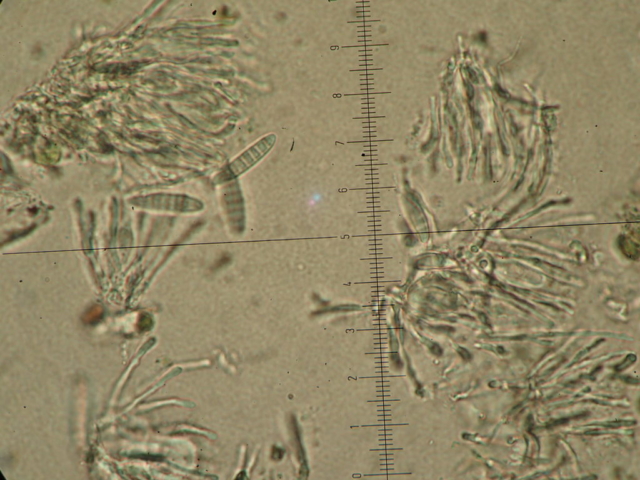

Marchantia polymorpha ssp polymorpha proved to be the most ubiquitous thallose liverwort on vertical soil banks all along the beck, with very little Pellia sp present. Plagiochila spinulosa was also found here, together with Fissidens dubius, Trichostomum tenuirostre and Scapania undulata. Platyhypnidium riparoides and Hygrohypnum luridum were common on boulders in the beck itself, together with Thamnobryum alopecuroides, and small bright green patches of Lejeunea patens. Vertical rock above the water-line had cushions of Amphidium mougeotii. Following the beck upstream we found small base-rich areas with Ctenidium molluscum and Tortella tortuosa. Unfortunately, the flushes here were mostly covered with snow, however Sphagnum rusowii and Leiocolea bantriensis were found suggesting that these areas would merit another look. Lunch was necessarily brief due to the penetrating cold, however it did allow us to time to appreciate the stunning views down Ullswater. Two very confiding robins also came to investigate us and hoover up any crumbs. Further up the beck, water was still flowing in several flushes. Green cushions of Blindia acuta were found here together with Palustriella commutata, Hookeria lucens, Rhizomnium punctatum, Cratoneruon filicinum and Riccardia chamaedryfolia. Abundant dead wood was mostly snow-covered, but Riccardia palmata and Tetraphis pellucida were found. By about 2.30 fog started rolling down over Trough Head, so rather than start recording in a new monad we headed down the valley again to find the lichen group. On the way down, Frullania fragilifolia was found on a large Ash tree, its distinctive ‘pear-drops’ scent apparent even in the cold. Having seen no Bazzania trilobata all day, a small patch was located near the beck below the public footpath. As the light was fading, a tiny Lophozia with red gemmae was found on a very large oak tree on the northern boundary. This could be L. excisa or possibly L. longidens, and has been sent to a referee for determination.

Altogether just over 90 species were recorded, but this would undoubtedly have been higher without the snow. A further visit is clearly required.

Kerry Milligan