I’ve recently been browsing a set of reports that Francis Rose wrote for the Nature Conservancy Council in the early 1970s. Mainly, but not exclusively, about lichens, they contain a wealth of information about the visits he (with others including Brian Coppins and our own Russell Gomm) made to Cumbria’s woodlands in search of epiphytes. They are fascinating reads, in oh-so-many ways.

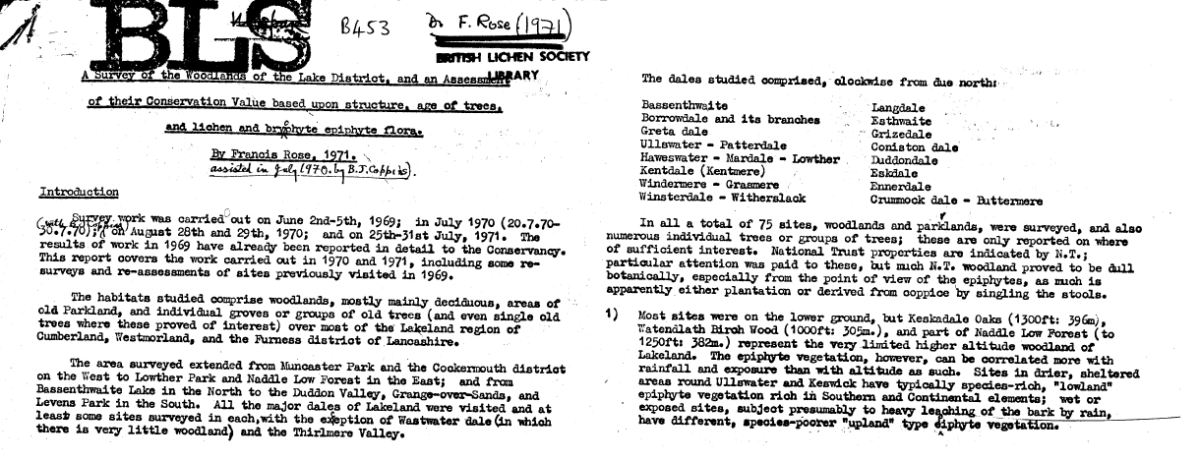

Firstly, there’s the human stuff: there was a lot of searching and lichen bothering going on, in fair weather and foul. The main (1971) report covers 24 days during which he visited 75 sites plus additional trees, not to mention the areas that were looked at but didn’t make the cut. Many of the woods that he identified as being the best in Lakeland are still regarded as such: Seathwaite, Yew Crag, Scales Wood, Naddle. Some that are now recognised as being very important, like Rydal, didn’t get the attention they maybe deserved.

The reports give a marvellous sense of an understanding being developed. The factors influencing which woodlands are good for which lichens in Cumbria are being observed and weighed: the indices of ecological continuity are on their way to being sorted. Sites in drier, sheltered areas (with basic barked trees) tend to have a different (and possibly more species-rich) lichen flora than more upland, wetter woodlands where the nutrients have presumably been leached from the bark. These days, the differences are recognised in the Southern Oceanic Woodland Index and the Upland Rainforest Index.

But woodland history and management override other factors: young/ coppiced woodlands have more limited epiphyte populations. And then there’s air pollution: the effects of coal burning and sulphur dioxide production were much more obvious then. The northern and eastern Lakes, more sheltered from the effects of industrial pollution, had retained better lichen floras. There’s also the soil: not only do more basic soils allow ash and elm to grow, but oaks on more basic soils tend to have richer lichen floras. And as soon as one starts to climb through a wood, the effects of leaching are visible: the higher parts of wood have a more “upland, acid bark loving, flora”.

All of which hold true today, but when it comes to the species, the reports can read as though they are talking about somewhere completely different. Obviously, many of the species names have changed; many more lichens are now recognised and described. But Parmotrema perlatum was only found at one site in the Windermere/ Coniston/Ambleside area (these days it is prolific) and Normandina pulchella is noteworthy as an indicator of relict Lobarion: how some things have bounced back! Maybe, to look on the bright side, there are more lichens now in many places.

Another example of how things have changed is the description of Physcia aipolia as “interesting”. It is, these days, prolific on my soft fruit bushes. The Xanthorion is held to be an interesting community: the prolific growths of nitrophilous lichens that we see today are far from being an issue. Lowther Park is described as being “probably the richest so far discovered” in Northern England. My explorations there suggest a lot of nitrogen enrichment, and the loss of all the interesting lichens. One report gives details of individual trees: it will be worth revisiting these to see what exactly is there today.

Overall, it is probably the losses that stand out more than the gains: Great Wood, Borrowdale, was described as having the three Lobaria species in an “abundance unparalleled in Northern England”. Whilst some (of all three) remains, the elms are gone and the decline in Lobarion well known. Across Lakeland, these excursions came across large old trees that retained lichens from pre-industrial times; wayside oaks with Sticta limbata, Lobaria virens and Nephroma. Fifty years on and they aren’t on the roadsides, though some of the old ash pollards have them just about hanging on.

On the other hand, some things remain the same: the “abundance” of Bryoria fuscescens in Holme Wood, Loweswater, that struck Francis Rose is my main memory from our 2020 visit. And then there’s the things that were found that need searching for again: Usnea ceratina in Pull Garth Woods; Heterodermia obscurata at Lodore. If these reports do one thing, they urge us to get outside with a hand lens. Cue the suggestions for next winter’s programme!

And finally, it is interesting to note the report’s recommendations: that many of the sites in Borrowdale should be “given National Nature Reserve status within an envelope”, and other sites given protection too. Fifty-plus years on, it may be that the former is being considered. Was that the sound of a stable door I just heard?

Text and photos: Pete Martin