On the day before the trip date, the weather was appalling, with strong winds and relentless heavy rain, and the weather forecast was not amazing, so we set off for the day with some trepidation to see how the weather would evolve. There was a lot of standing water on the roads, with quite long stretches of the Burton road submerged, but two of us arrived safely at the meeting point on the A5084, near the small road to Stable Harvey (SD 28934 91049). There was a surprisingly good turnout, with eight people in the bryophyte group.

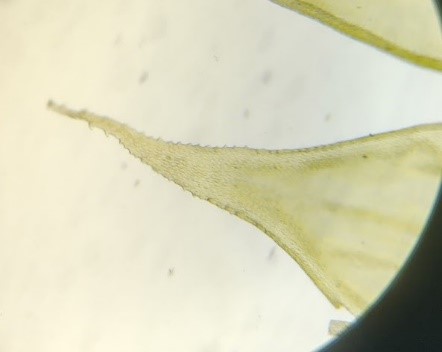

With the benefit of local knowledge from Rob, we decided to have a quick look at the quarry where some of us were parked. It was indeed a good site and the bare quarry floor was almost entirely carpeted in bryophytes, including Philonotis fontana, small amounts of Dichodontium palustre, Didymodon insulanis, Campylium stellatum, Cratoneuron filicinum, Calliergonella cuspidata and quite a surprising amount of Palustriella commutata (not as regularly pinnate as you would normally expect, but showing all the other features – plentiful rhizoids and paraphylla, curved leaves etc.). We had two beginner bryologists joining the group for the first time, so this was a good opportunity for teaching / revising some common species. The walls of the quarry also had quite a good variety of species: large quantities of Kindbergia praelonga in one corner, also Schistidium crassipilum and some small cushions of fruiting Ptychomitrium polyphyllum. At the far entrance there was further evidence of base-rich substrate, with Tortella tortuosa and Ctenidium molluscum. It was nice to see a good cushion of the tufa moss Gymnostomum aeruginosum, as well as Ptilidium ciliare and a small patch of Scapania compacta.

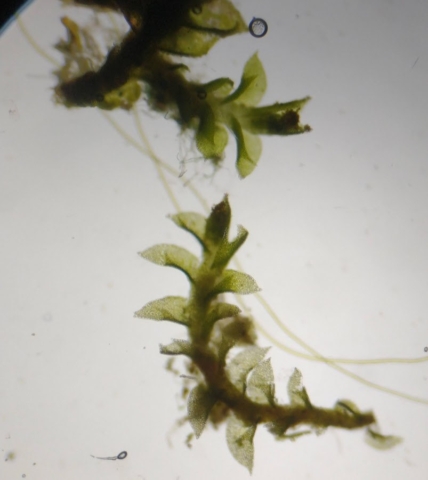

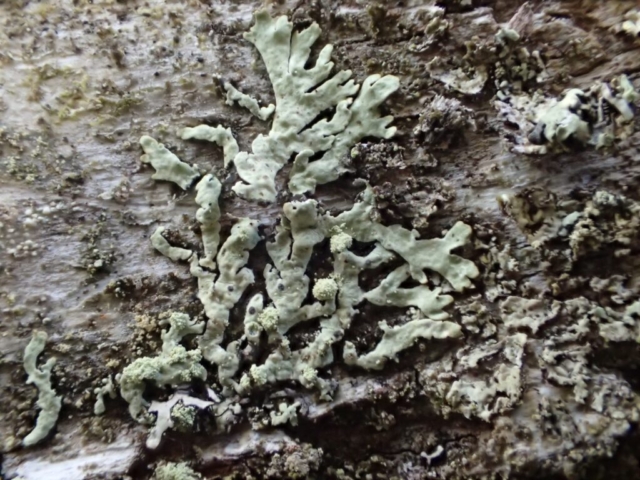

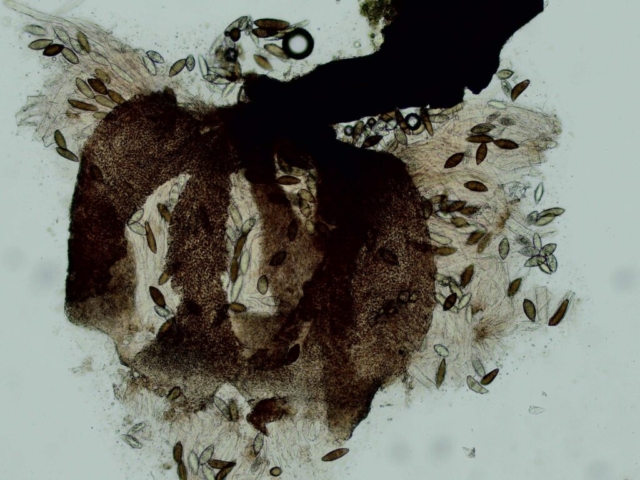

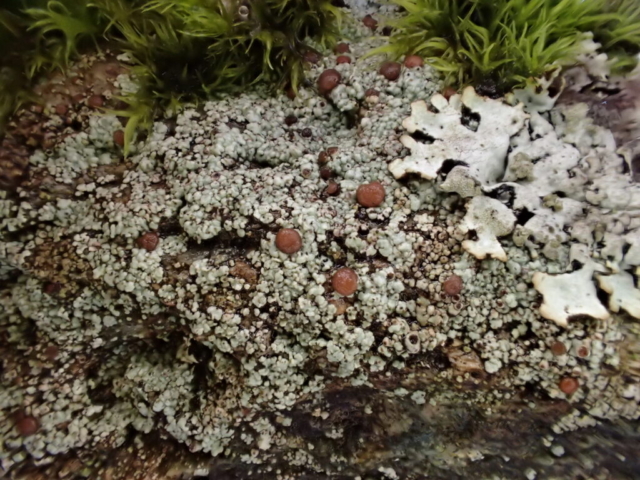

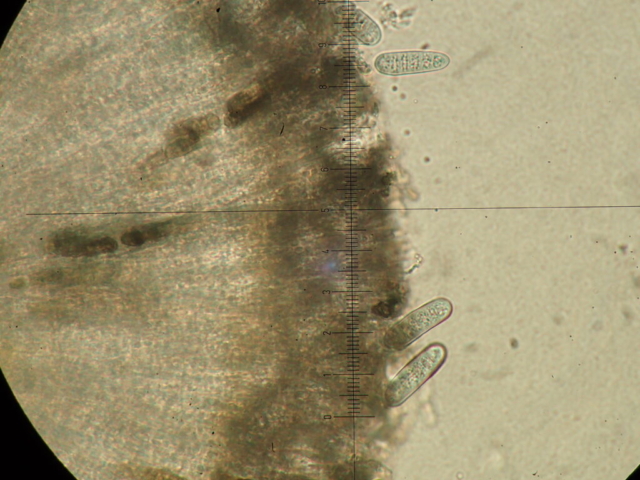

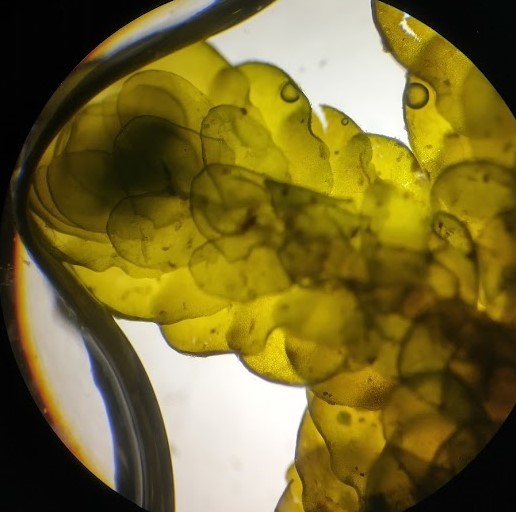

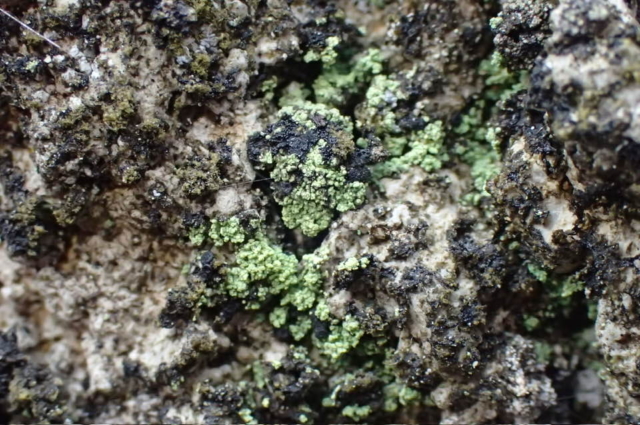

After a good explore of this area we thought it was time to head for the mires on Blawith common. We splashed up the Stable Harvey road, stopping to admire some lovely patches of the lichen Pannaria conoplea on an old ash (see lichen report!). The lower stretches of the road pass through open woodland with birch and some old ash and oak. Spotting a waterfall just off the road, we headed off to explore. The waterfall had Chionoloma tenuirostre, Metzgeria conjugata and a few nice cushions of Amphidium mougeotii (another tufa moss), but sadly no Jubula hutchinsiae, which has however been recorded in this tetrad. A veteran oak overhanging a rock face had a big cushion of prolifically fruiting Leucobryum at its foot – the capsules (with a white calyptra and distinctive but small bump at the base) pointed to L. glaucum as L. juniperoideum is more rarely seen fruiting and the capsules are slightly different. A sample was examined in case it was L. albidum, but it was confirmed by Tom Blockeel as L. glaucum. Hanging off the rock face, on a mat of decaying vegetative matter, was a small amount of Lophozia incisa. There was also some nice, gemmiferous Lophozia ventricosa on a tree root, Gymocolea inflata on a rock and a potential Rhytidiadelphus subpinnatus. We had lunch near the waterfall, then headed back to the road under a grey sky and light drizzle. Some flat rocks near the road had Polytrichum pilliferum, Racomitrium lanuginosum and Pogonatum urnigerum with Bryum alpinum and Breutelia chrysocoma in seepages. By the road edge there was some gold-tinted Sphagnum inundatum.

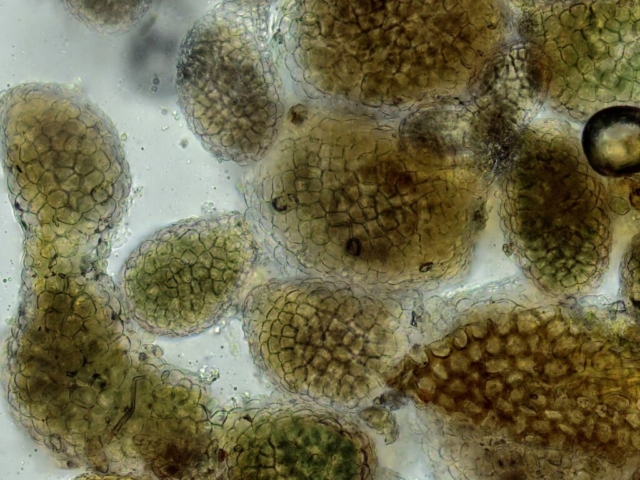

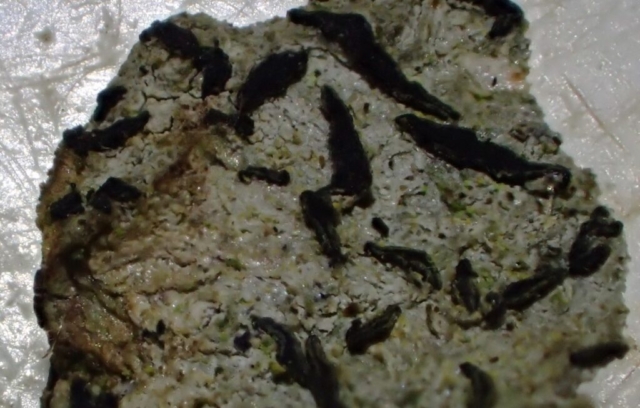

A little way up the road, we finally reached the mire, which at first was rather poor, mainly Molinia and Myrica gale with only small amounts of Sphagnum beneath. We collected a couple of Sphagnum species, then headed across the road to a better site, where there were cushions of Polytrichum strictum and Aulocomium palustre, as well as several Sphagnums: S. capillifolium subsp. capillifolium, S. auriculatum, S. fallax, S. inundatum, S. palustre, S. papillosum and S. russowii. There were patches of Odontoschisma Sphagni and one patch of Mylia anomala, with only a few shoots showing clusters of gemmae after the heavy rain. Straminergon stramineum was poking its head out of some of the mounds. A small escarpment of rocks above the mire had Andreaea rothii and Ptilidium ciliare.

A cold wind was starting to blow, so we decided to beat a retreat. It was an enjoyable day, and undoubtedly far better than any of us had been expecting.

Text and photos: Clare Shaw