As part of the North Pennine ore fields, the geology of the western slopes of Dufton Fell is interesting – mineral-rich veins intruded into sedimentary layers (limestone, sandstone, shale, coal), all exposed in an upland valley. The Whin Sill (quartz-dolerite) is nearby and a few boulders of that were seen. Mining for lead started in the 1700s but turned to baryte production in the 1890s. Some exploratory work was carried out during WWI and in recent times the spoil heaps were reworked in the 1970s and 1980s, ie not much disturbance from mining in the last few decades so some of the spoil heaps are slowly vegetating over with low-growing plants and moss. However there were signs of digging, probably to use the spoil as gravel for track surfacing etc.

The site is part of the Appleby Fells SSSI which covers most of the north Pennines. It is designated mainly for habitat, eg limestone grassland, and associated plants and birds, although the geology too gets a mention. Specialist mine spoil habitats are not included.

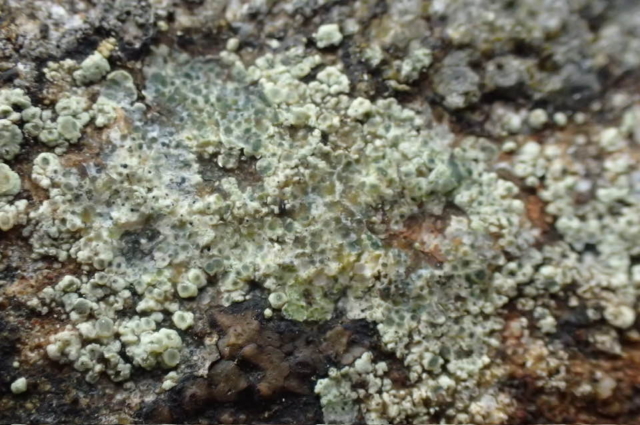

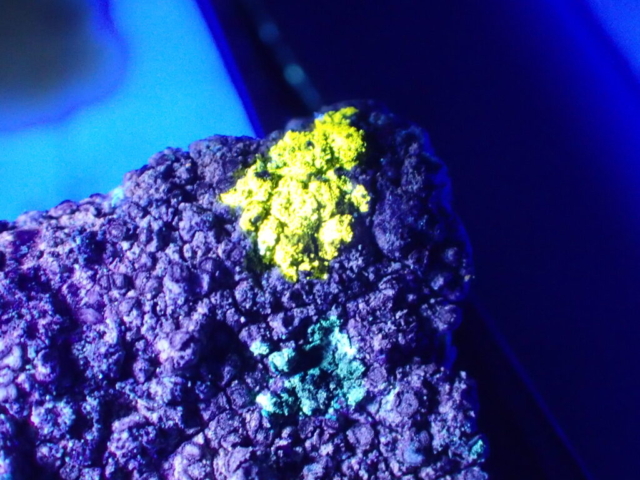

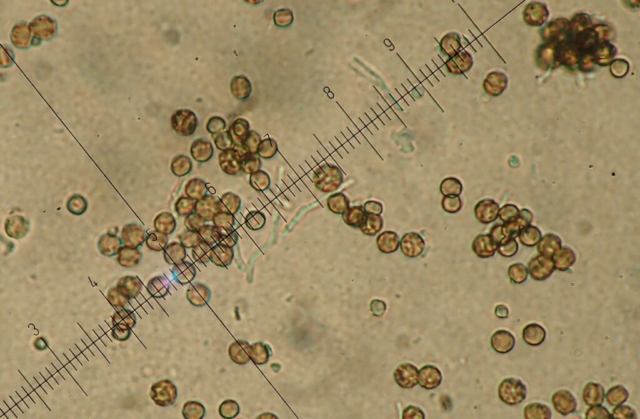

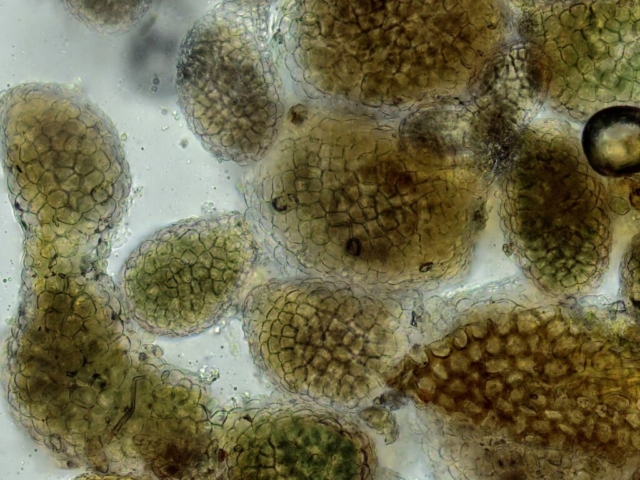

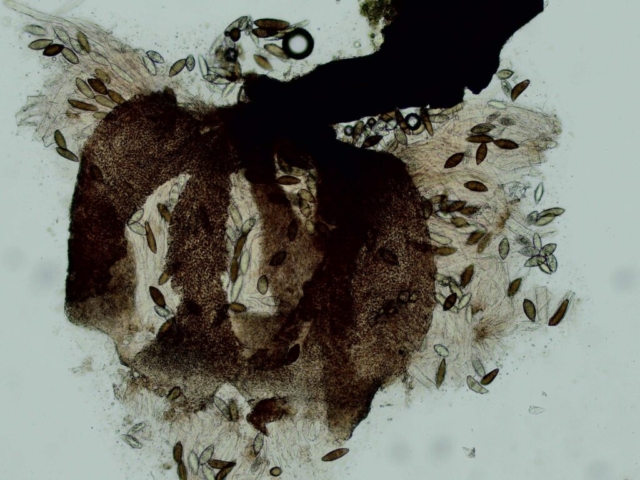

We were aiming to reach the upper mined area, at about 550m, in monad NY7127. It’s over 4km (2.5miles) up hill from Dufton to this point on a good track all the way. Once into the monad there’s a good range of limestone and gritstone boulders and outcrops above Great Rundale Beck, as well as lots of mixed mine spoil. We stopped here near a lime kiln for a while and saw most of the species found on our earlier recce – assorted jelly lichens such as Lathagrium cristatum and L auriforme, Solorina saccata and Secoliga jenensis. Also here was Trapelia coarctata on a tiny slate pebble plus a new find: Nationally Rare Sagiolechia protuberans on limestone, showing a few black apothecia with exploded star-shaped margins.

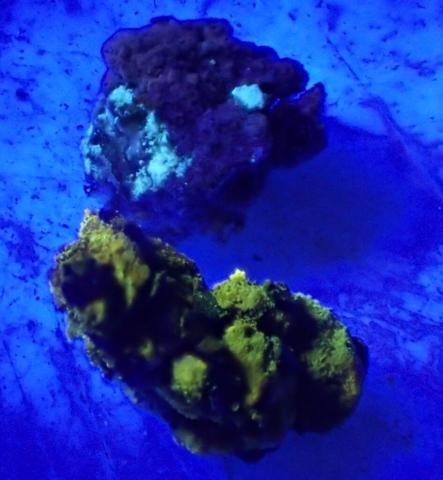

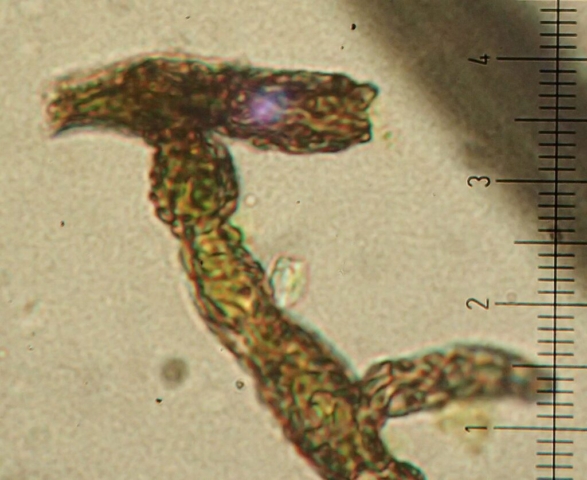

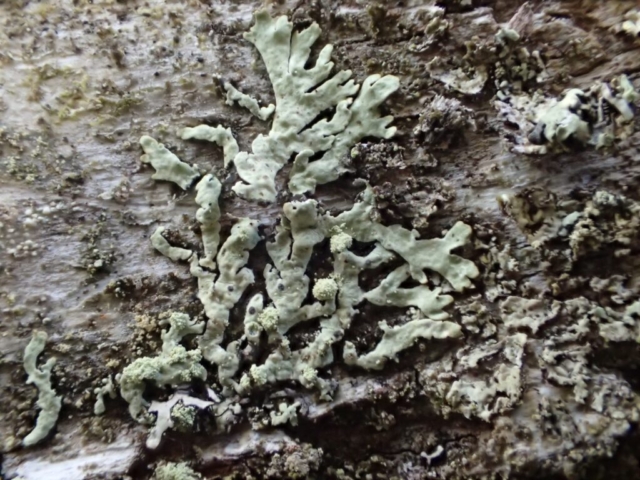

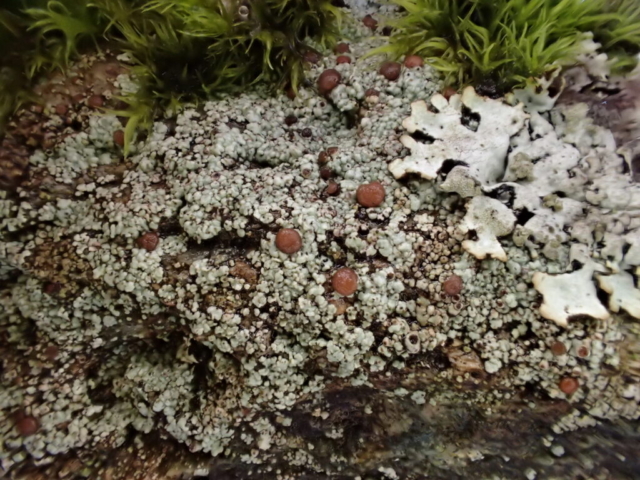

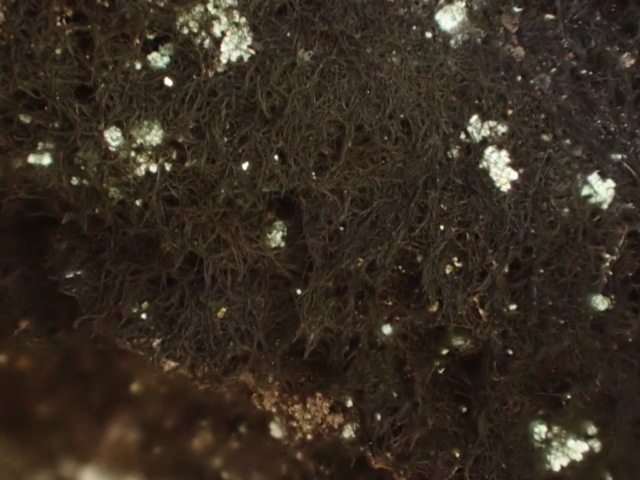

We carried on up the track to an area of gentler slopes of gravelly spoil where the rare lichen Peltigera venosa was found back in January. It was still there though many of the tiny thalli were blackened and dying – was this to do with the drought a month or two back? As we carried on uphill it was seen in several further spots so still enough of it around. On the higher spoil heaps were mounds of terricolous species looking much more exuberant than usual – Cetraria islandica, C aculeata, Dibaeis baeomyces and Cladonia rangiformis, amongst others. Was their size and abundance due to the lack of competition, access to minerals plus hydration where the ground was boggier ?

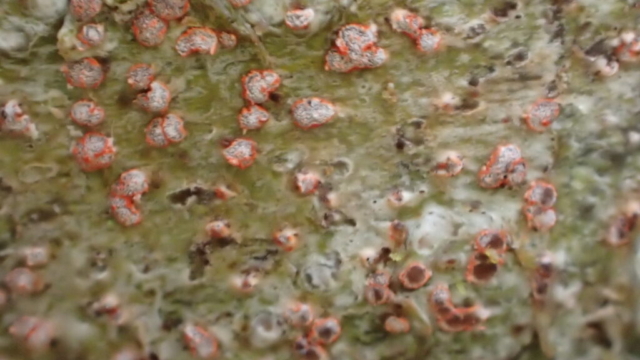

John Douglass spent most of the time looking for Rhizocarpon species for an ongoing project, but took the time to point out a candidate for Cladonia borealis, a rare member of the red-fruited Cladonia coccifera group. It has a bare corticated podetium and shallow cup containing flattened granules.

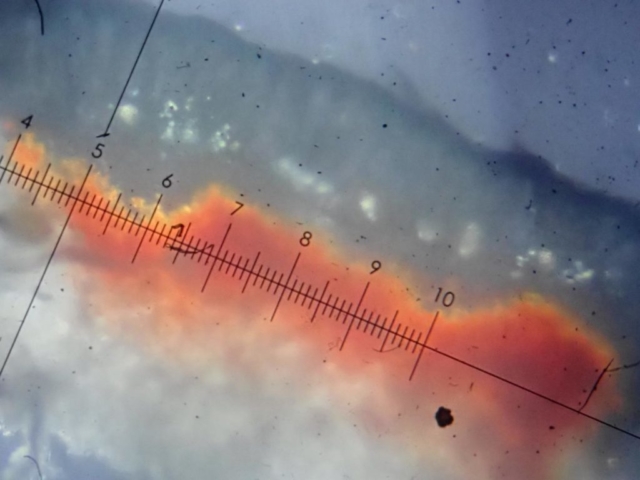

Other finds included Baeomyces placophyllus, another terricolous species associated with metal-rich sites, and Trapelia placodioides on an outcrop which showed a vivid C+red reaction.

The limestone influence even in the spoil heaps was very obvious with calcareous flora around – thyme and mossy saxifrage were flowering and several tiny moonwort ferns became apparent because we had our faces pressed to the ground. Chris also found a nice horn stalk-ball fungus growing on the keratin of a sheep skull.

Before our visits this year there were no lichen records so it’s been rewarding to fill in some blanks on the map for this interesting upland site. There’s plenty more ground to look at too, so as usual we may have to go back…

Text: Caz Walker

Photos: Chris Cant, Caz Walker