A large group met at High Wallowbarrow Farm in the Duddon Valley on a sunny autumn day. There are few lichen records here, monad SD2296 having 34 mainly from 1970 (Brian Coppins and Francis Rose). We started by looking in the next square to the west which was unrecorded. This is a formerly coppiced wooded slope where alder, birch, hazel and oak grow amongst huge mossy boulders and outcrops.

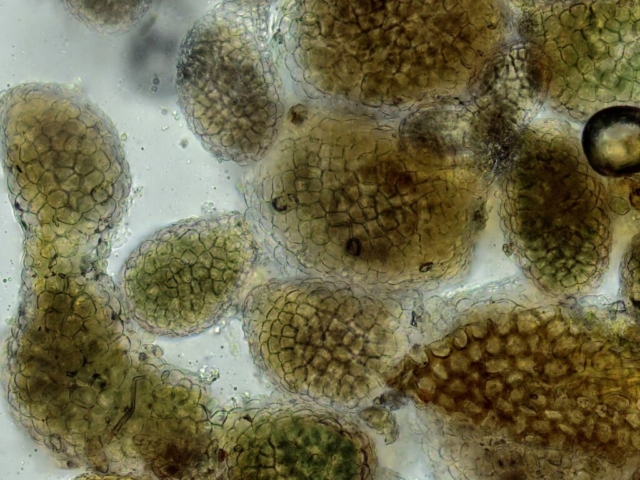

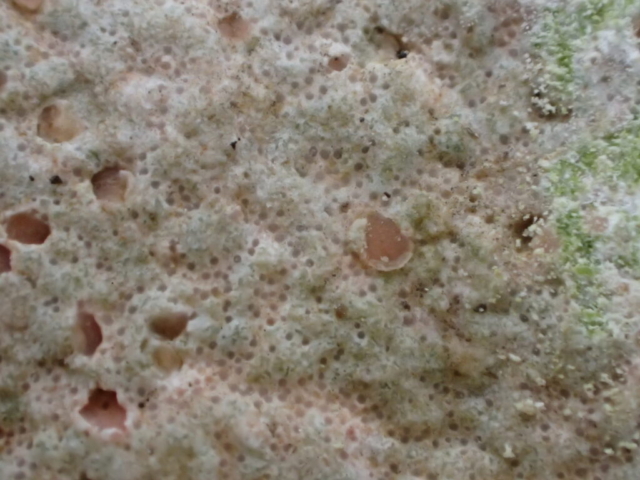

It was slow going as every tree and rock needed examination, with lots of lichen chat. Many participants were complete beginners while others had come on trips earlier in the year and remembered enough to have a go at identification – and could help those who knew less. Normandina pulchella on several hazel trees proved popular, as well as discussions around various Cladonia species. A large boulder had a granular yellow-green and orange patch of Trapeliopsis pseudogranulosa as well as some crustose Pertusaria species to which chemicals were applied in order to confirm the identification with a colour change.

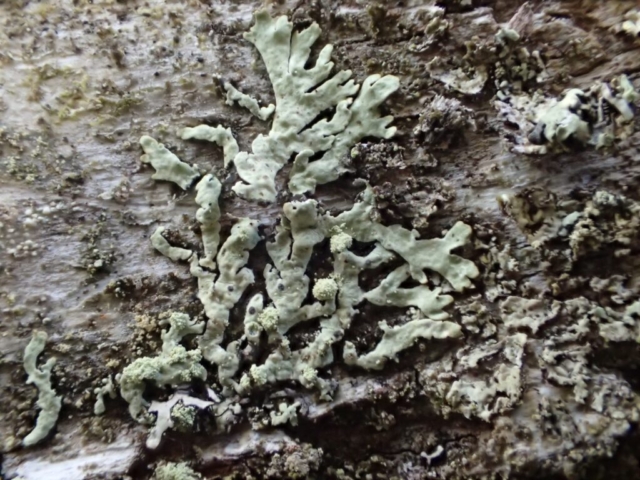

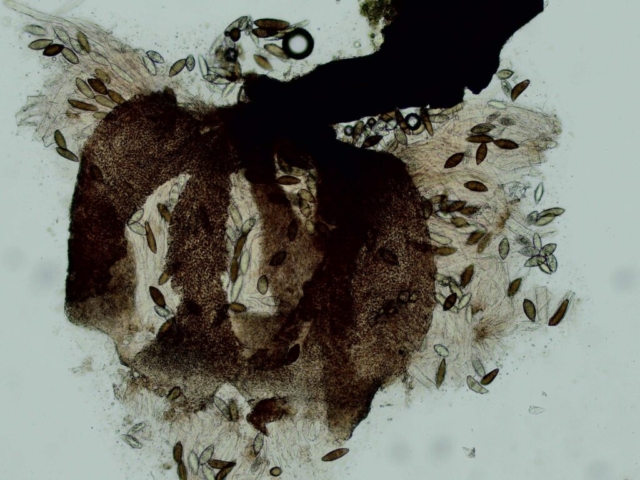

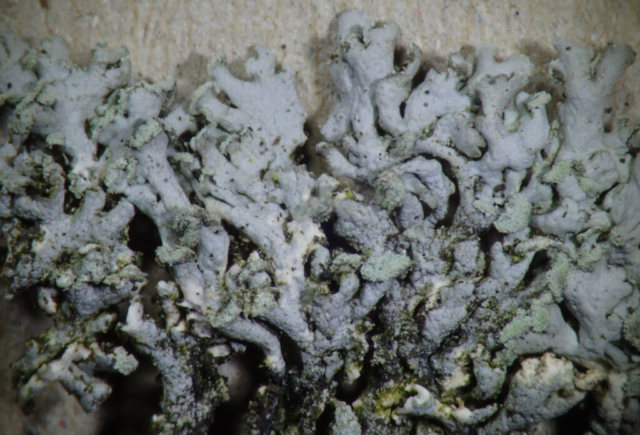

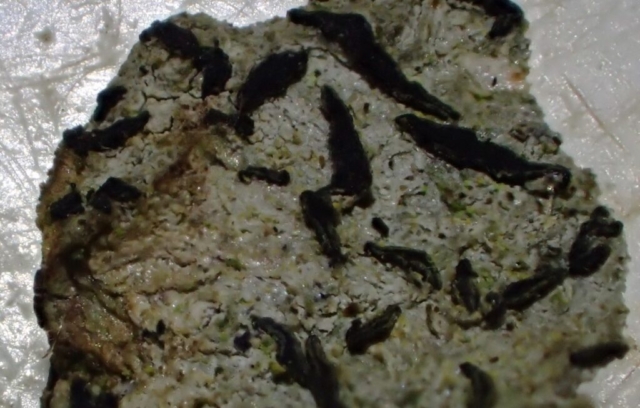

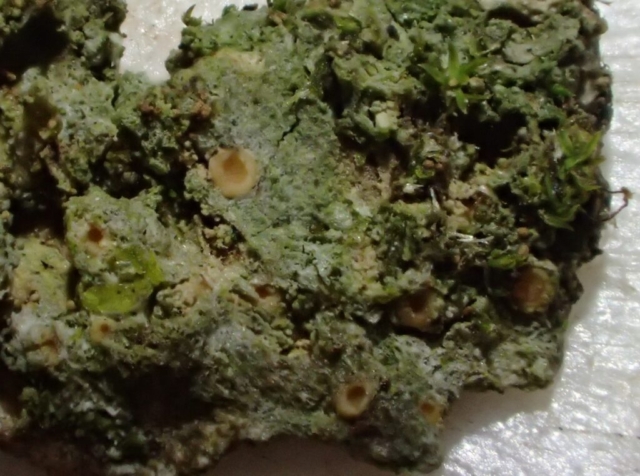

John Douglass, a lichenologist based in Scotland, was with us and helped point things out to everyone, including Micarea alabastrites with flat, white apothecia on a mossy alder and crustose species, such as Rhizocarpon infernulum f. sylvaticum, Porina lectissima on a mossy boulder high in the wood and both Trapelia glebulosa and T involuta growing side by side on a massive boulder beside the path near the farm. The latter is a distinct species but has been confused with T glebulosa in the past. Also here were Arthrorhaphis citrinella, easily identifiable with a bright yellow-green granular thallus and, in this case, fertile with black apothecia, as well as Placopsis lambii, a crustose lichen which has the appearance of lobes around the edge as well as flat patches of grey soredia, making it very recognisable. Nearby a birch had tiny neat pale yellowish rosettes of Parmeliopsis ambigua, with soredia arranged in globose soralia on the narrow lobes. Furrowed lirellae of Graphis elegans were on the same tree.

After lunch John headed to the river to search for aquatic lichens (his specialism) on damp rocks beside the river, finding Porina rivalis, new to VC70, as well as commoner species like Massalongia carnosa, Ephebe lanata and Ionaspis lacustris. The rest of us moved slowly along a dry stone wall, finding lots of lichen interest. Geoffrey enjoyed exploring the species there with Carole and Paul, taking the time to look closely at some tiny features. These walls can be very good for lichens and this was no exception – many little habitat niches supported plenty of common species as well as Stereocaulon pileatum and some good Cladonia species, such as the red-fruited C diversa and C bellidiflora. Mature oak and ash in the pasture had a range of foliose lichens and a hazel at the woodland entrance had the typical smooth bark species Pertusaria leioplaca and Arthonia radiata.

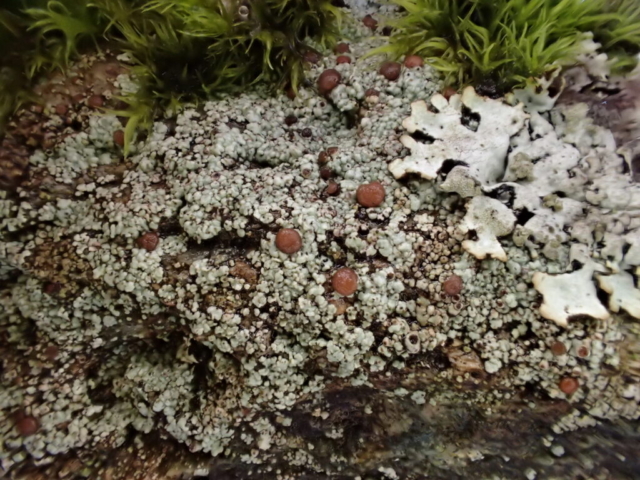

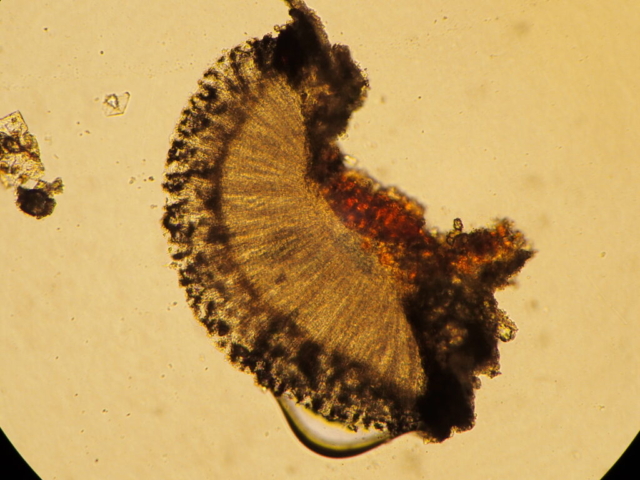

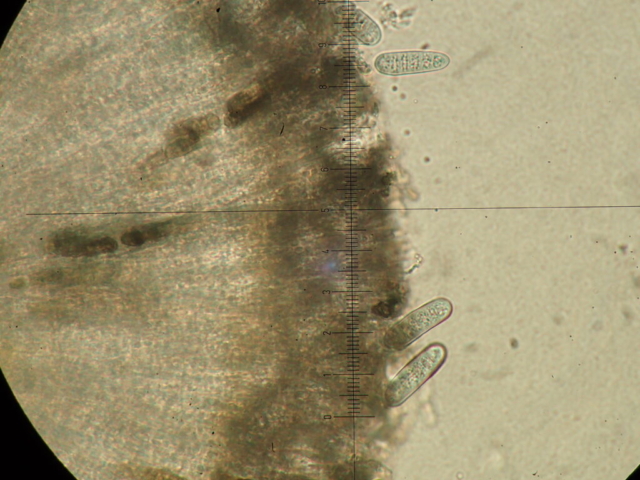

A final mossy boulder had good Cladonia which deserved close inspection, Cladonia caespiticia being the most obvious as it was fertile with tiny pink mushroom-like structures and minute dark pycnidia on the squamules. Also here was Cladonia squamosa showing pink brown apothecia – it’s not often seen fertile.

Overall there was something for everyone here but the feeling was that quite a lot was missing – there wasn’t the range of lichens or bryophytes we might expect at a good site. Kerry pointed out that the area had been intensively exploited in the past – heavily grazed, coppiced, trees felled for firewood etc – not to mention over 100 years of pollution from the industrial SW Cumbrian coast, all of which explains what we see, or don’t see, today. The recovery of the biodiversity may take many years.

Text: Caz Walker: Photos: Caz Walker, Chris Cant, Geoffrey Haigh, John Douglass