Continuing my theme of upland lichens, Caz Walker and I visited Little Dun Fell in the Pennines on 7/6/21 hoping to acquaint ourselves with the arctic-alpine species that have been found there, as well as to see how they are doing. We approached from a friends’ house in Eden valley fellside, so quite a trek with 11 miles total and 600m of ascent! We saw a ring-tail hen harrier on the way up, along with a couple of curlews and golden plover, though perhaps there should have been more. There weren’t very many flowers but a red admiral butterfly perched on the rocks at the summit of Little Dun Fell (which is just inside the Moor House NNR). The boulders also hid several bits of flotsam including two fluorescent rucksack waterproof covers and that not so rare species Plastic pepsicola.

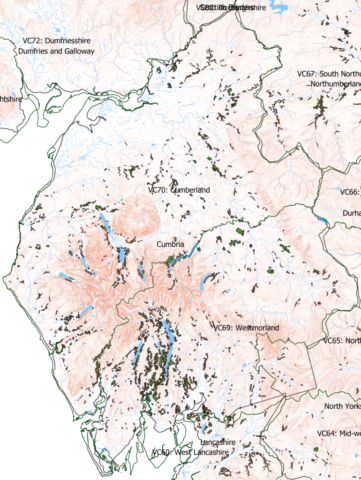

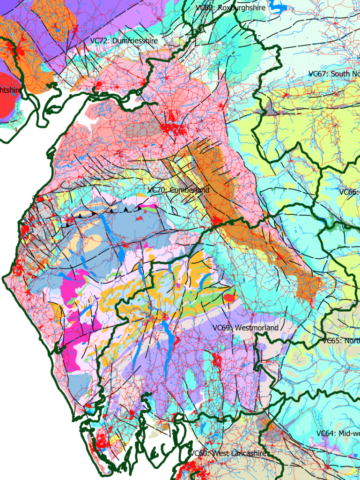

Little Dun Fell, Great Dun Fell and Cross Fell are on the Pennine Way in Cumbria with tops at over 840m: a layer of hard acidic gritstone, interbedded with other sedimentary rocks, showing as outcrops on the sides of Cross Fell and a boulder field just to the north of the summit of Little Dun Fell. Great Dun Fell sports a “golf ball” radar station – a landmark visible from afar on the west, and looks like a modern art installation close up.

The altitude and geology of these windswept tops provides a suitable home for various arctic-alpine lichen species that are more usually found on the tops of Scottish hills. Most of the lichen records are from some time ago, though Allan Pentecost visited Cross Fell summit in 2016. The last lichen records for Little Dun Fell in the British Lichen Society database are from 1979 at a BLS field trip which spent a week in the Penrith area (1). Some notable records have a 6 figure grid reference while others just have a hectad reference.

Caz had seen a few of the target species on trips in Scotland with the BLS montane group. We should also recognise other montane specialists that we’ve seen in the Lake District fells. We made a good list of species, re-finding some of the rarities and adding one more. However, Umbilicaria proboscidea was missing, having been described as locally frequent at Little Dun Fell in 1979. We also didn’t see Arctoparmelia incurva which had been present then, but we could have missed it this time.

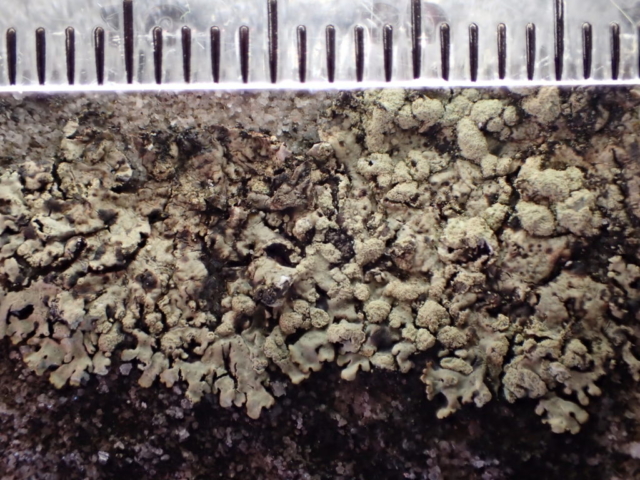

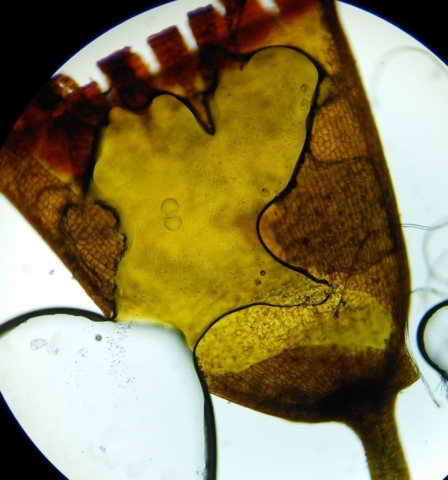

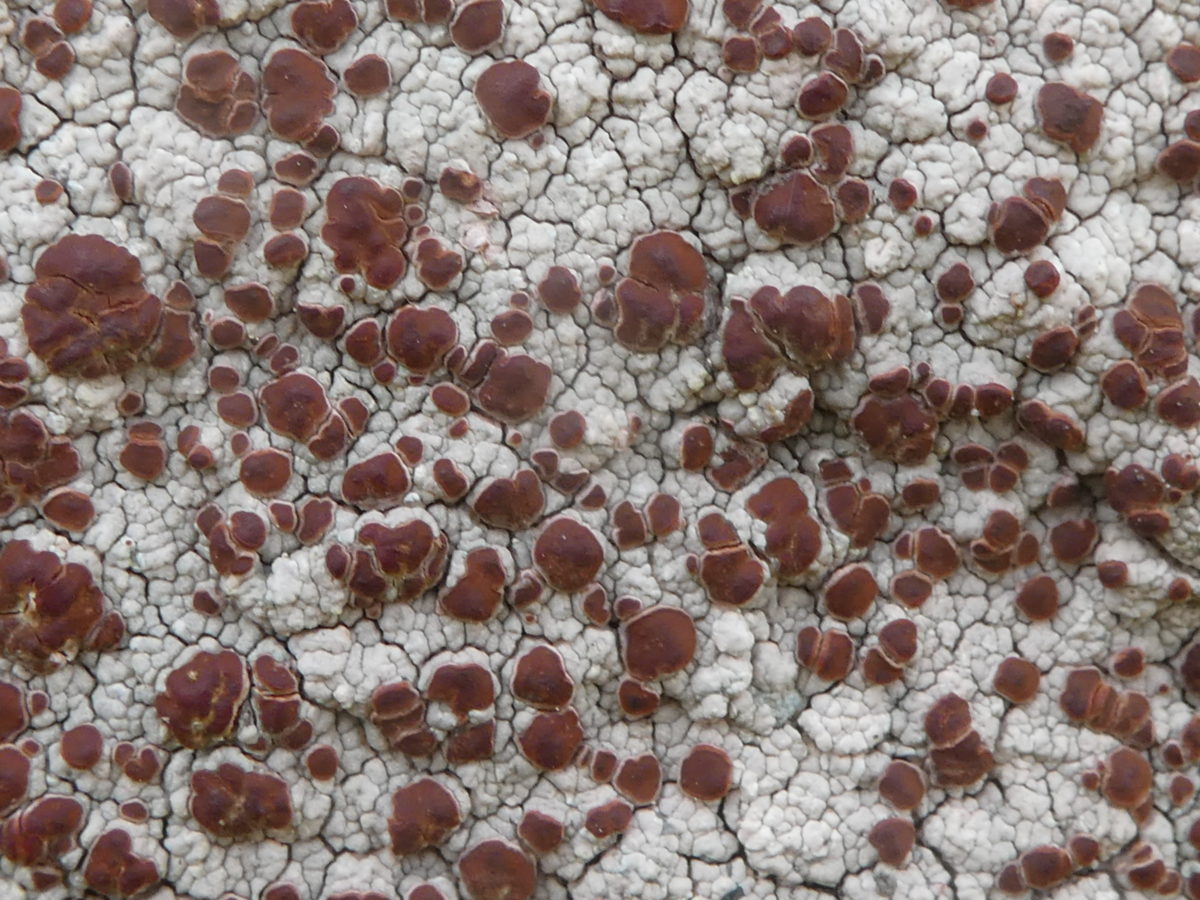

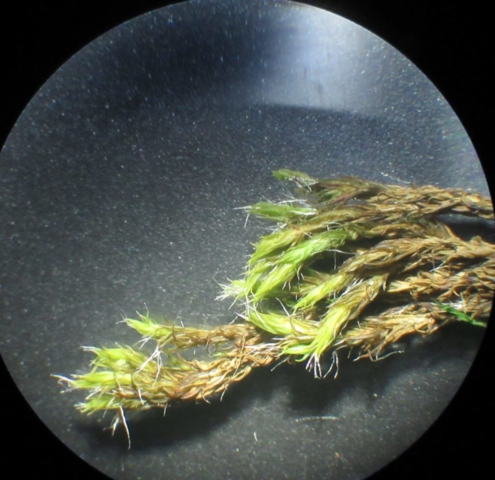

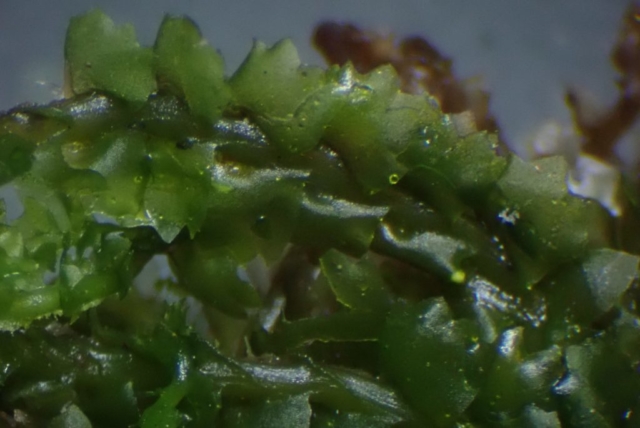

We re-found nationally scarce Allantoparmelia alpicola on quite a few boulders – tiny contorted and convex lobes. In addition we found two small appressed species that look a bit like Cetrarias. Cetrariella commixta was there previously, but Melanelia hepatizon is new for this top, though found west of Cross Fell in 1990 by Simon Davey. The M. hepatizon had pseudocyphellae on the lobe margins and the surface of the thallus; not present on the upper cortex of the C. commixta. More definitively, in M. hepatizon the white medulla is K+ yellow while in C. commixta it is K-. Note that the algal layer will turn greeny yellow during the test.

We also found Parmeliopsis ambigua on a boulder. This is mainly on acid barked trees, but it was found here in 1979 and there are a few other saxicolous records for Cumbria, with some of these on headstones in graveyards. It is yellow grey with globose soralia testing yellow with K. We wanted this to be Arctoparmelia incurva but that is KC+ pink and has different shaped lobes.

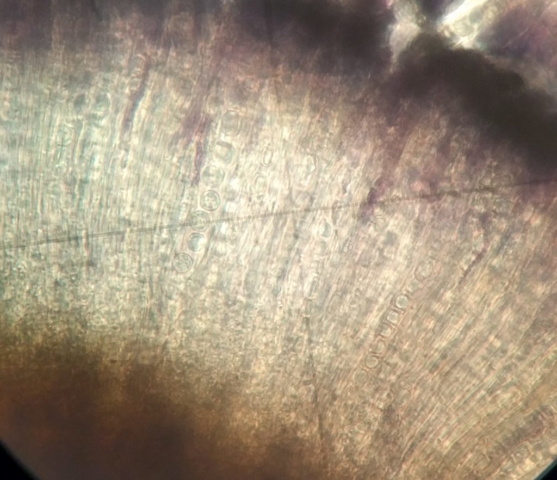

Schaereria cinereorufa was also present, with the uniseriate globose spores confirming it later.

In the turf, slightly surprisingly, was good old Bilimbia sabuletorum which we wouldn’t expect in an acid environment. However there is basic rock in the area.

Fifty metres closer to the actual summit there are two fenced exclosures, erected in 1954. The 1979 BLS trip report says that these had taller vegetation inside, with Cetraria islandica and Cladonia arbuscula having increased their cover to form large cushions. The exclosures are still there with intact fences, but we saw neither of those species in a quick look, though we did see Cladonia ciliata. The inside vegetation is indeed slightly taller, but not a lot, so the extremes of weather do stop dominant species even with no grazing or trampling. I don’t think the two lost species were present outside of the exclosures in 1979, presumably due to grazing or historic burning. But any chance of recolonisation now seems to have gone. Update: We did see Cetraria islandica on a later visit to nearby Great Dun Fell and Cross Fell.

There’s a similar old exclosure at Cow Green Reservoir (also in Moor House NNR) that we visited on 29/7/20. The growth there was similarly slightly higher inside, and had bushy C. islandica along with Common twayblade and Cloudberry. So, it feels like the Little Dun Fell exclosures aren’t doing very well, even with grazers excluded. A long term study of the Moor House vegetation plots, 2015 (3), says that “during the period that Moor House has been protected as a nature reserve the vegetation quality has declined in spite of reductions in grazing pressure.” The study reports Little Dun Fell as having the highest numbers of sheep (at 5.8 per hectare average between 1954 -1998) but says that “overall, removal of sheep grazing had few positive effects and many negative ones”. It doesn’t reach any definitive conclusion as to what’s going on but speculates that “it is possible that this reflects a continuing late-twentieth century impact of atmospheric pollution”. Increased temperatures from climate change won’t help.

That report also says, “What is of particular concern are the reductions in the probability of occurrence of liverworts and lichens.” “Biotic homogenisation has now been detected in Great Britain at the countrywide-scale (Smart et al. 2006) and within alpine communities (Britton et al. 2009 (4)), and it is possible that this reflects a continuing late-twentieth century impact of atmospheric pollution”. A paper from Mitchell in 2017 (6) echoes these findings: less specialist species are invading the highest refuges for alpine species of various taxa. The combination of warming and nutrient loads in most uplands is therefore reducing biodiversity.

It would be good to check out more of these Pennine tops to get a better overview of the situation, so, as usual, a repeat visit is required, ideally with less of a walk-in. In particular it would be lovely to check the only English record of Umbilicaria hyperborea on Cross Fell, in the database for 1979 following its finding by Rod Corner in 1977 (2).

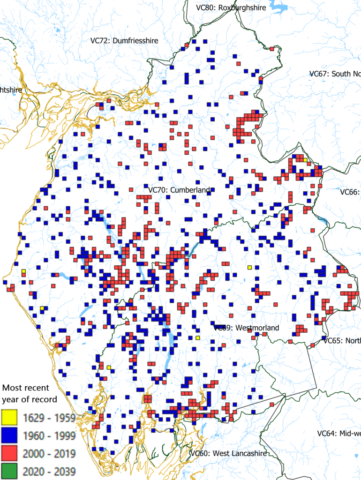

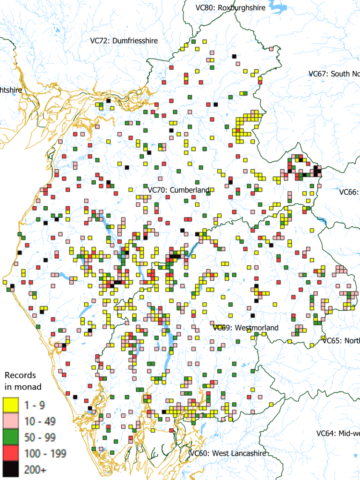

Re-finding existing records is great to build up your knowledge – and check the state of play on the ground. The distribution lichen maps for Cumbria are online here, and I can provide full records – and the BLS records officer is happy to provide database snapshots for other parts of the country. It’s also good to visit new areas – and thinking about the geology and vegetation can suggest where to look.

Chris Cant

- Coppins & Gilbert (1981). Field Meeting near Penrith. Lichenologist 13(2): p193

- Corner (1978). Umbilicaria hyperborea discovered in England. Lichenologist 10: p134

- Milligan, Rose & Marrs (2015). Winners and losers in a long-term study of vegetation change at Moor House NNR: Effects of sheep grazing and its removal on British upland vegetation.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82709587.pdf - Britton et al (2009) Biological Conservation 142/8 p1728-1739

Biodiversity gains and losses: Evidence for homogenisation of Scottish alpine vegetation

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320709001451 - Britton et al (2016)

Climate, pollution and grazing drive long-term change in moorland habitats

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/avsc.12260 - Mitchell et al (2017). Biological Conservation 212 p327-336

Forty years of change in Scottish grassland vegetation: Increased richness, decreased diversity and increased dominance

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320716310722