We started the field meeting at a small lay-by in Legburthwaite with a good turnout of around 10 bryologists. A last-minute illness meant our group lead was unfortunately unable to attend, but we still set off up the trail to High Rigg with a hopeful outlook on a drizzly but mild November day.

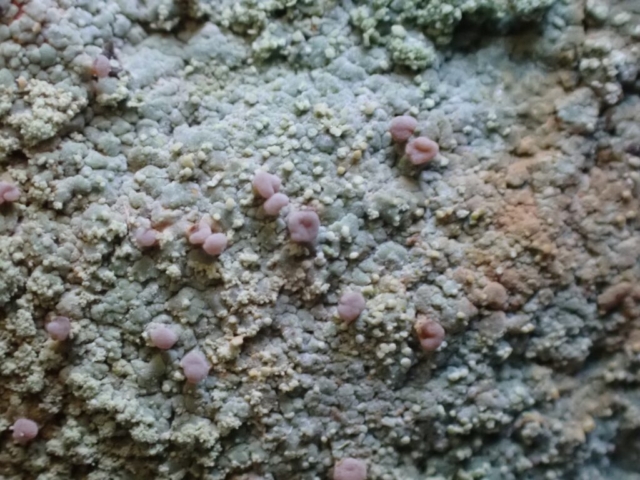

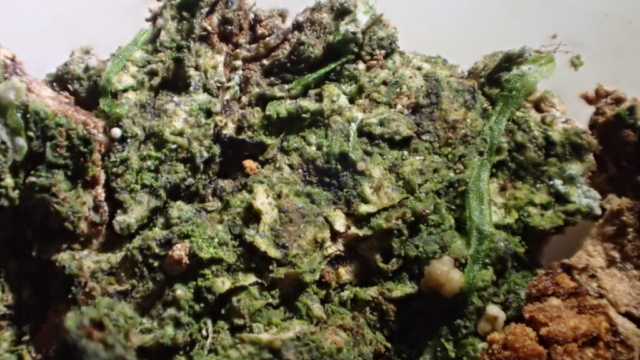

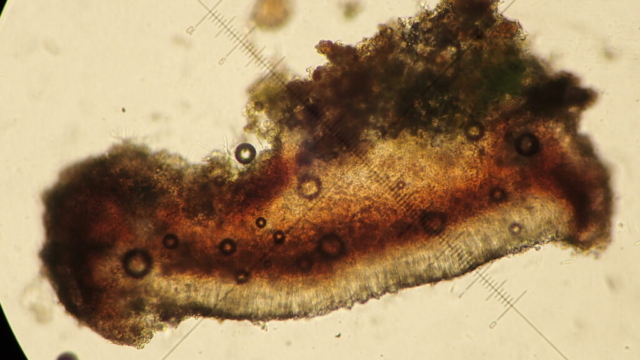

A brief hike up the path to Wren Crag brought us into monad NY3120 where we started our species recording on a rocky slope, finding many common upland species including Polytrichum alpinum, Orthocaulis floerkei, and Pogonatum urnigerum. There were signs of oceanic climate indicators in the rocky outcrops and sheltered crevices, particularly the liverworts Scapania gracilis and the more restricted Orthocaulis atlantica, distinguished from the aforementioned O. floerkei by the presence of red gemmae. Other liverworts here included both Lophozia excisa (with red gemmae and abundant perianths) and Lophozia sudetica (with many brownish gemmae and eroded leaves on gemmiferous shoots). The moss Leptodontium flexifolium caused some confusion. It looked rather like a Pohlia and was only identified under the microscope from its very papillose cells and large marginal teeth. It occurred in two forms in two different locations on the site: one small, looking rather like a Barbula species, and the other with more drawn-out shoots and deciduous bulbiform branchlets looking rather like Pohlia bulbils. It is fairly common in such acid habitats as this but we may be tending to overlook it as a Barbula.

After an ambling climb uphill, we decided to pick up the pace and push further into the centre of the monad towards some promising mires and pools surrounding the High Rigg trail. While many distracting crags were found along the way, the wet heaths provided some great common acid indicator species such as Pleurozium schreberi and Hylocomium splendens. As we headed down into the mire, the species composition suggested a base enrichment entering via the springs and flushes in the area, and the Sphagnum species composition highlighted this variance nicely. The group quickly totalled up thirteen species of sphagnum, including Sphagnum russowii, S. girgensohnii, and S. auriculatum in good numbers in the base-enriched areas. The base influence was also supported by further discoveries of Calliergon giganteum around a pool and Hypnum cupressiforme var. lacunosum appearing on the surrounding slopes and scree.

After a quick stop for lunch the group decided to head back down the path to enter the monad from a lower location via a riverside path. Here a few of our members parted ways and a smaller group headed out to explore the lightly wooded scree slopes on the east-facing side of Wren Crag.

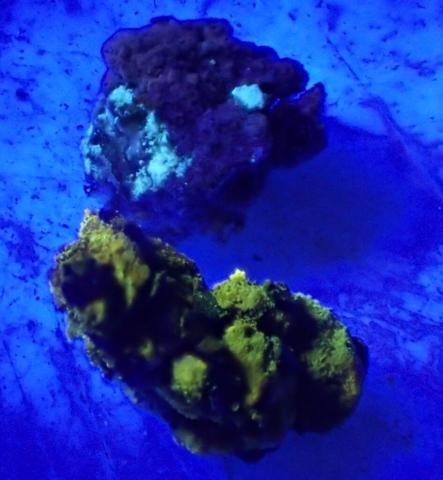

The find of the day was Ptilium crista-castrensis which appeared in surprisingly large numbers across the slope, with several well-established patches discovered during the afternoon. Spirits were further raised by the discovery of the western species Frullania fragifolia, an almost-black liverwort that lives up to its name; the fragile leaves practically fall off in your hands!

Overall, we recorded 107 species of bryophyte, and the site provided a good variety of different habitats to reinforce upland species learning. With many beginners on this trip, it provided a great opportunity for knowledge sharing and conversations around how and why our species form different distributions in the uplands and in microhabitats. Thanks to everyone that attended and contributed to species recording!

Text: Josie Niemira

Photos: Josie Niemira