The May meeting took place at Side Wood, on the southern shores of Ennerdale Water. Side Wood was previously part of the adjacent Ennerdale Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) but now lies within the Pillar and Ennerdale Fells SSSI. The SSSI citation states that the site exhibits one of the best examples of altitudinal succession in England. From upland birch-oak woodland at 120m on the shores of the lake, the vegetation changes through sub-montane heaths and grasslands to montane heaths along the summit ridge at an altitude of 890m.

Side Wood is one of the best examples of upland birch-oak woodland (National Vegetation Classification (NVC) community W11 Quercus petraea-Betula pubescens-Oxalis acetosella woodland) in west Cumbria. The citation describes lichen communities within the woodland as being of regional importance “with rare Ochrolechia inversa occurring abundantly on birch”. This species has been re-named Lecanora alboflavida since the citation was written.

We met up at Bowness Knott Car Park and then car-shared and travelled along a gated track to another parking area, closer to Side Wood. After crossing a few open fields, which held little to distract us, we arrived at the edge of the wood and our first tree; a not very healthy-looking hawthorn, with many of the common species such as Evernia prunastri, Hypotrachyna afrorevoluta and Ramalina farinacea present. It was at this point that a passerby stopped and asked us if we were looking at lichens by any chance. He had recently listened to a very interesting and informative podcast by somebody called Pete Martin! Pete was duly pointed out and delivered an impromptu short introduction to lichen thallus types.

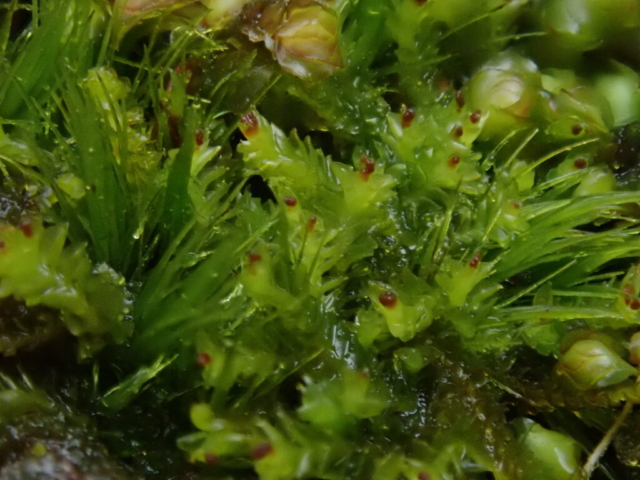

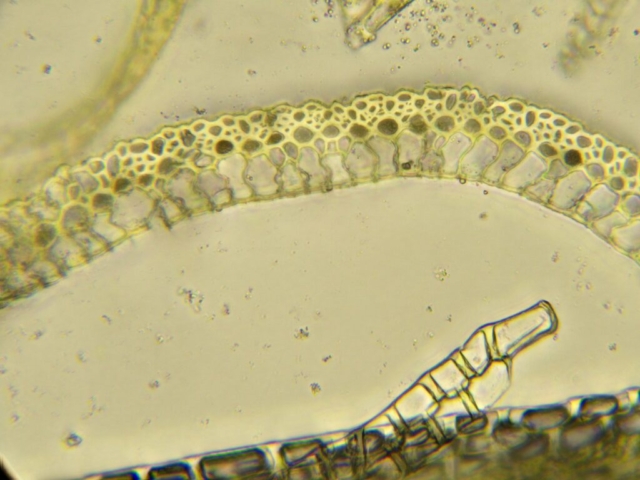

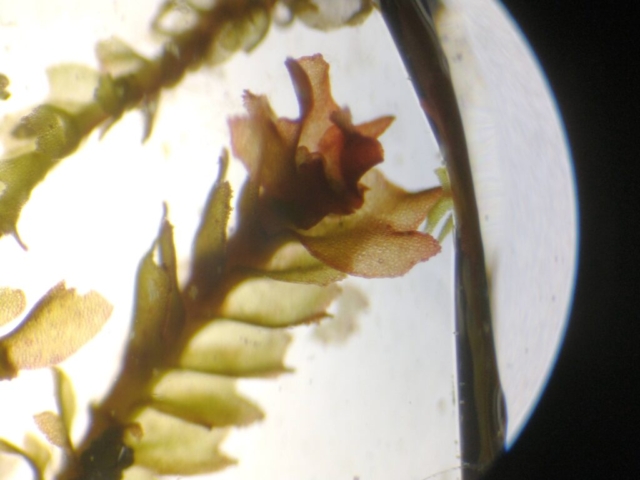

Venturing further into the wood it could be seen that the best trees for lichen were the mature birch. The mature oak trees were mostly covered in dense mats of mosses and liverworts, as were the majority of rocks on the woodland floor. It was good to see some extensive patches of Wilson’s filmy-fern Hymenophyllum wilsonii though, a species mostly frequently occurring in western Scotland, Cumbria, Wales and Devon/Cornwall.

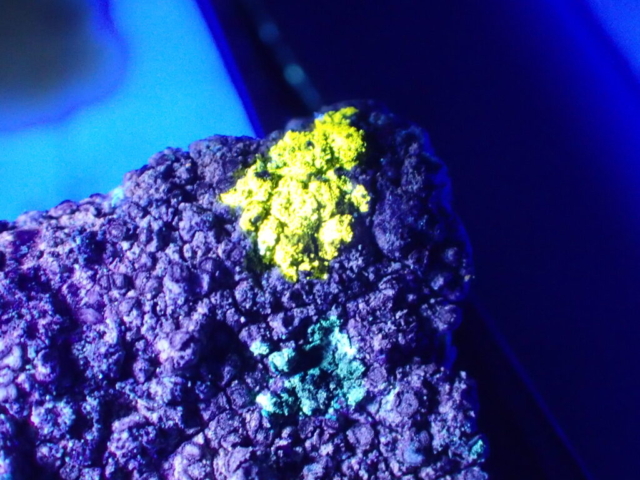

One of the first notable lichens found was Lecanora alboflavida, on birch. It was quite non-descript with a yellowish sorediate crust, with a C+ orange reaction but was easy to distinguish from surrounding lichens by the very bright UV+orange reaction. It seemed to be frequent on birch throughout the woodland. Other frequent species throughout the woodland included Thelotrema lepadinum and Hypotrachyna laevigata.

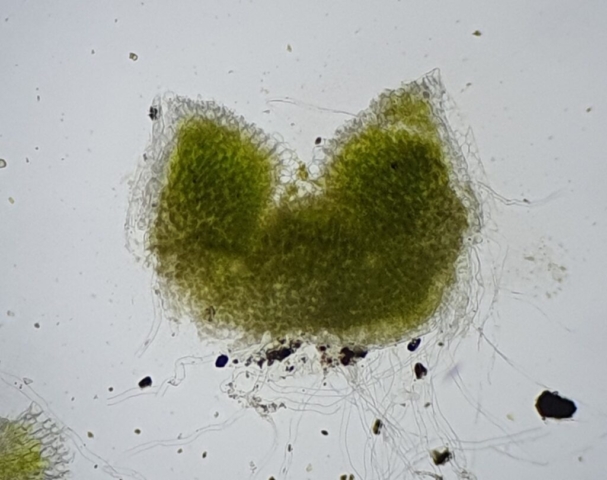

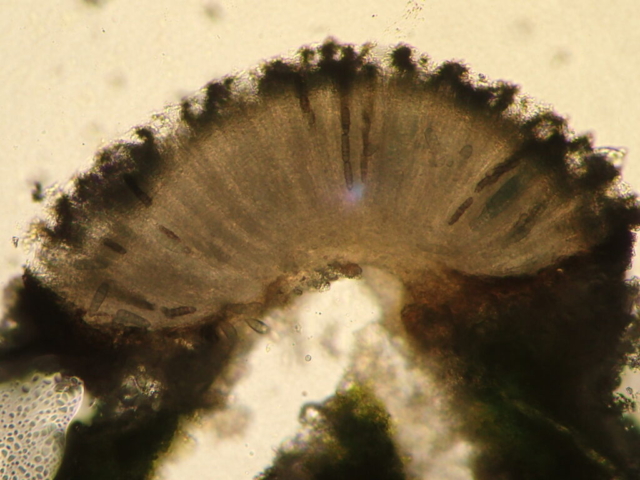

As we climbed further up the hillside the number of midges also increased, encouraged by the warm weather and still conditions. Despite this distraction though, lots more interesting species were recorded. The highlight for me (being a relative beginner) was the fertile Bunodophoron melanocarpum, with its large black spore-covered apothecia, growing on damp rock, high up in the woodland. We also found large amounts of non-fertile Bunodophoron growing on rocks and trees and the closely related Sphaerophorus globosus growing on birch trunks. The damp rocks were also the location of another very attractive species; Icmadophila ericetorum, which Pete said is often referred to by the slightly less attractive name of “fairy vomit”; a very good description though! Close-by to the fairy chunks was a small patch of Lichenomphalia umbellifera thallus, consisting of small clustered green granules. I have previously seen the toadstool-like fruiting body but not the granular thallus. An impressive patch of abundantly fertile Ochrolechia tartarea was also present on exposed rock.

Pete pointed-out Mycoblastus sanguinarius on birch which was very distinctive where apothecia had fallen out, revealing bright red spots formed by the medulla below. Another first for me was Coenogonium luteum, famous for being on the cover of the seventh edition of Dobson, but under the previous name of Dimerella lutea. The Coenogonium was growing on moss (Hypnum cupressiforme), attached to an oak tree, in a similar fashion to the way Normandina pulchella was growing on mossy trees.

Towards the end of the day me, Pete, Caz and Chris headed down towards the path which ran along the lake, to head back towards the cars. There was a bit of a breeze by the lake and fortunately the midges gave up following us around. It was here that Caz spotted another scarce species, Cetrelia olivetorum, growing at the base of an oak right next to the water. There was also a large patch of what could possibly have been some more Cetrelia, higher up on the trunk and out of reach. Luckily there was another large patch of what turned out to be Cetrelia on the base of a die-back ash on the opposite side of the lakeside footpath. The same ash also supported a small amount of Hypotrachyna sinuosa, another scarce species in Cumbria. After this we all headed back to the cars after what was a very enjoyable day. Apologies if I have missed out any important records as many of the lichens are still new to me.

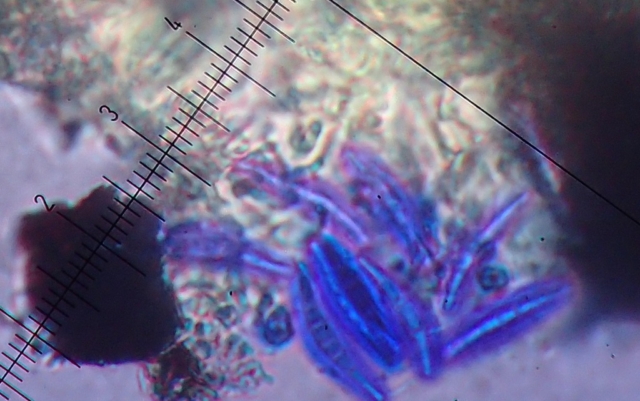

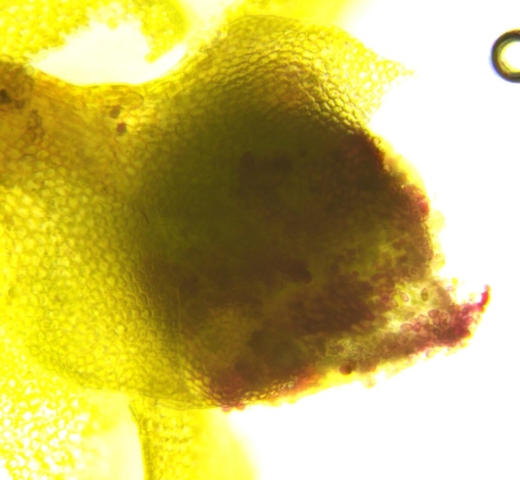

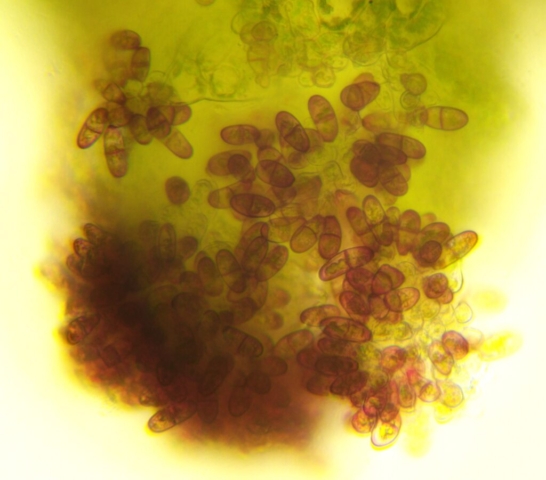

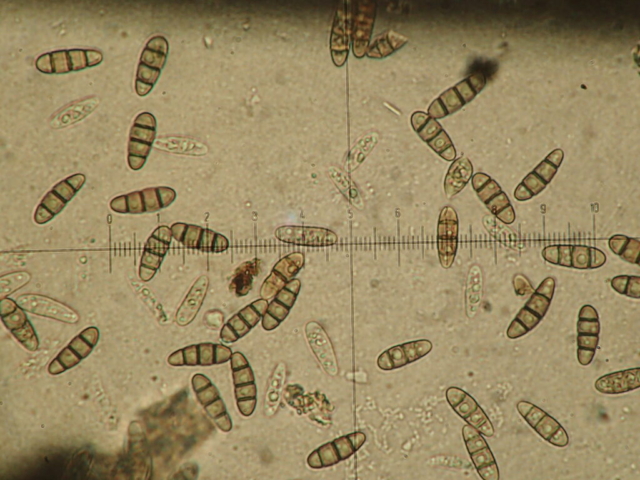

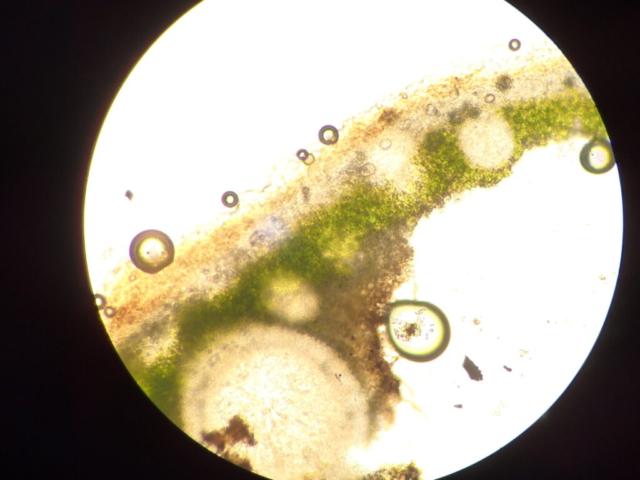

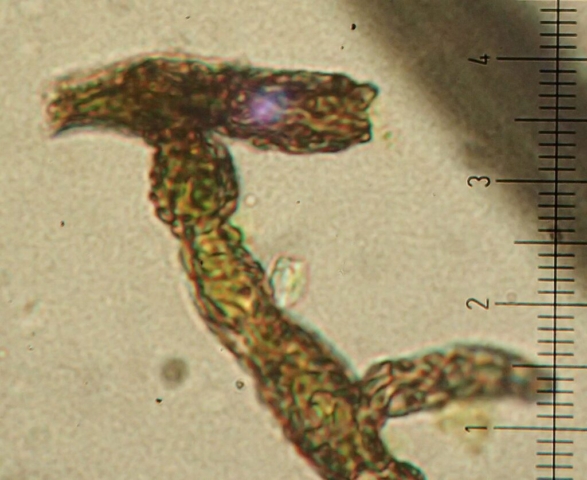

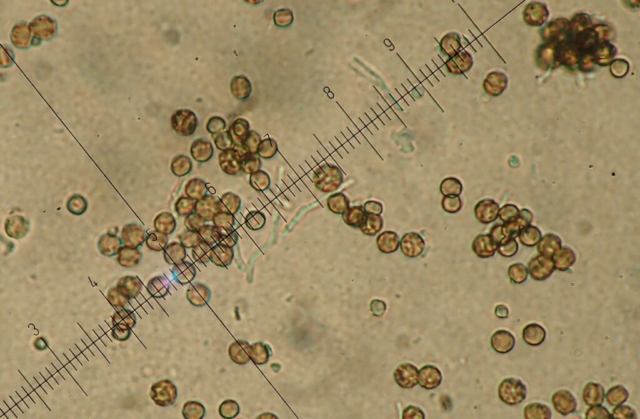

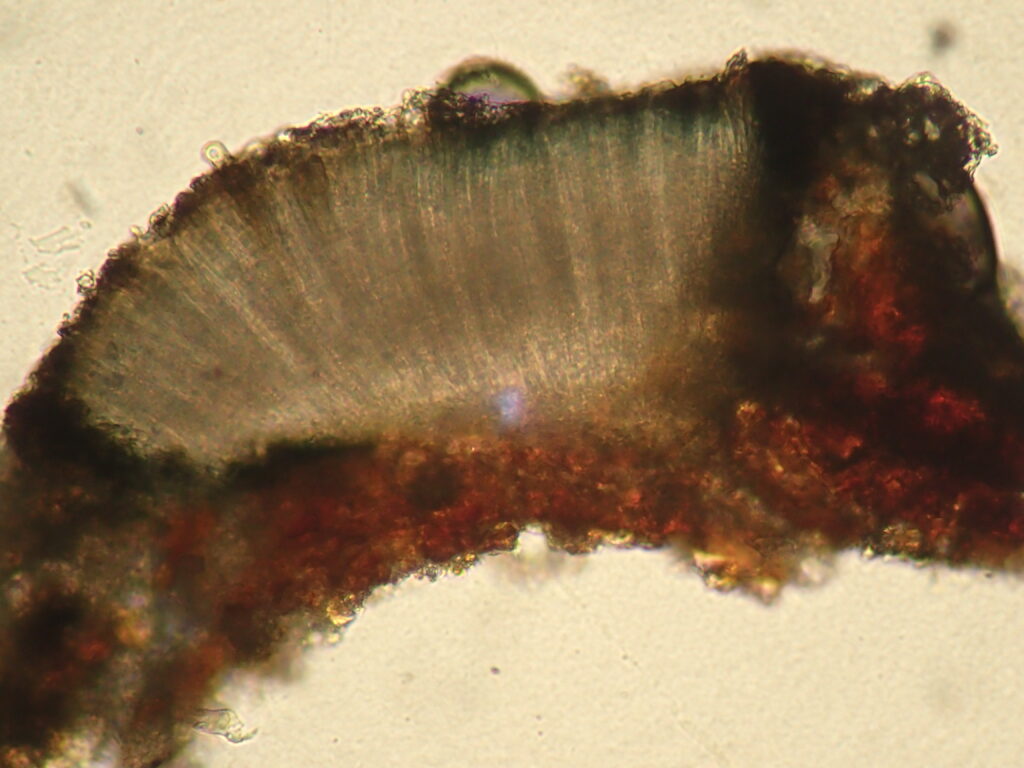

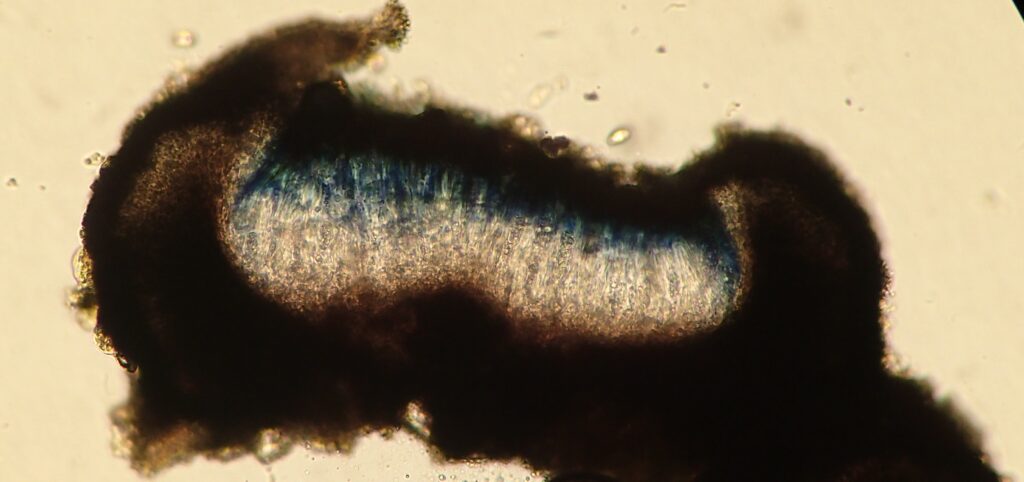

Caz and Chris had also taken a sample of a species from hazel, thought to possibly be Porina aenea, in the field, but after microscopic examination of spores and pycnidia, turned out to be Dichoporis taylorii (formerly Strigula taylorii). This was new to Chris and Caz and is only the third record for vc70 Cumberland.

Text: Paul Hanson

Photos: Paul Hanson, Chris Cant and Pete Martin

Note: the records list currently includes 11 lichen species that appear in the Upland Rainforest Index (URI). If the URI species count is 10 or more then the site should considered as eligible to an SSSI – see page 24 here. Further species may in the rest of the wood – which we didn’t visit.