Lichens at Ashness Wood and Moss Mire, by Watendlath Beck

There was a good turn out – 10 people looking at lichens – despite the weather forecast for a wet morning. After a few heavy showers we had a dry afternoon which allowed for some good licheneering.

This is a National Trust site, part of the Lodore-Troutdale Woods SSSI which is designated for its upland acidic oak-birch woodland and forms part of the internationally important Borrowdale Woods complex.

Most of the participants were new to the group and, in some cases, new to lichens so we took a while to get out of the Surprise View car park where the trees had lovely displays of acidic bark species, showing a range of growth forms and other features. Once everyone had had a go with x10 hand lenses and got their eye in for the tiny structures we need to look at in order to start the ID process, we set off, pausing to examine oak and birch trees along the way.

At Moss Mire, beside Watendlath Beck, we stopped for lunch and spent a few hours looking closely at trees (corticolous lichens), riverine rocks, shaded upland rock outcrops (saxicolous species) and terricolous habitats (lichens growing on the ground). This was in the southern part of monad NY2618; we ventured briefly into NY2617 as there seemed to be no records for that square and wrote a short list. All our records will be submitted to the British Lichen Society.

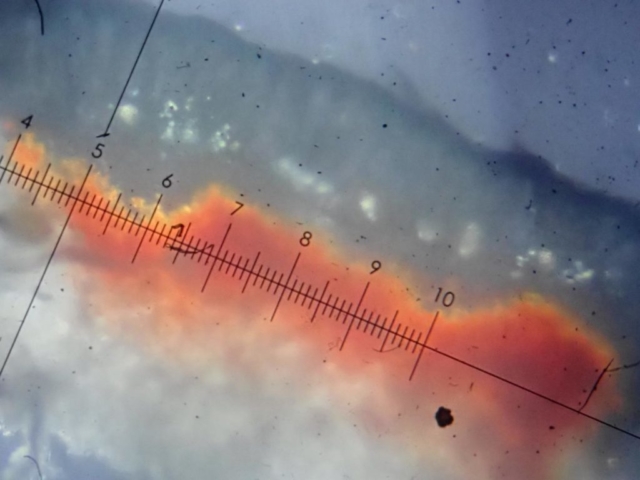

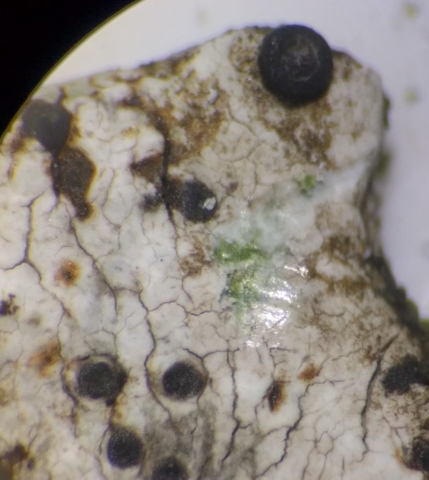

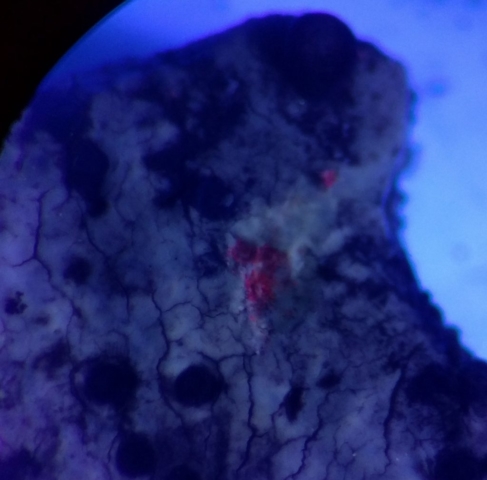

Mostly the species we saw were from the acidic bark lichen communities including Bryoria fuscescens, Sphaerophorus globosus, Ochrolechia tartarea, Ochrolechia androgyna, Dimerella pineti and Micarea stipitata. The Ochrolechia species allowed a demonstration of a useful chemical colour change where a drop of C (bleach) goes red. Mycoblastus sanguinarius was also common with red pigment visible beneath black apothecia. However some of this may turn out to be Mycoblastus sanguinarioides, only recently found in Britain, and distinguished by internal crystals which show up in polarised light under a compound microscope. It needs to be confirmed, but well done to Pete for taking a specimen and investigating.

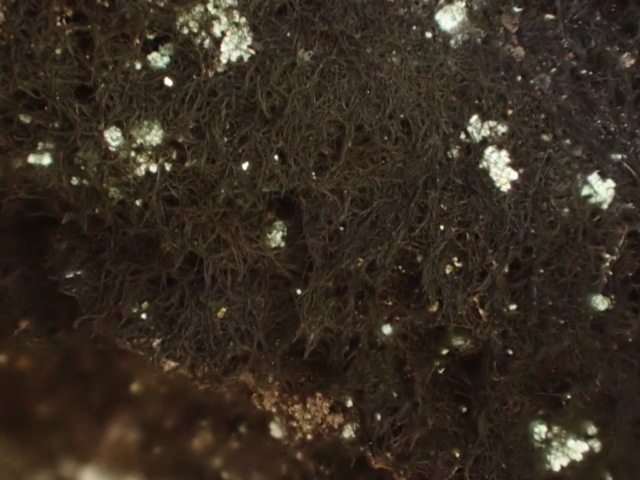

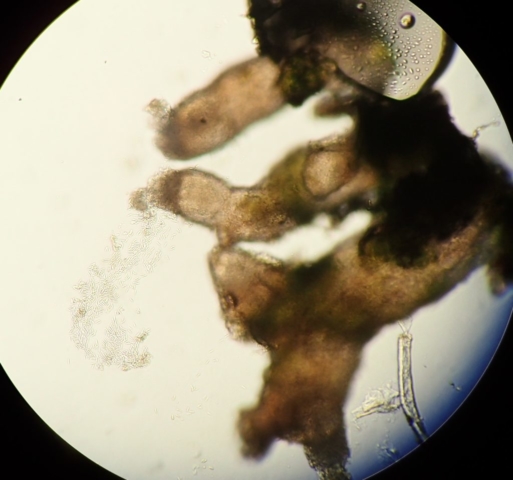

We also saw Thelotrema lepadinum, or barnacle lichen, which indicates good quality woodland, and black fuzz on mossy shaded rock which turned out to be two species, Cystocoleus ebeneus and Racodium rupestre. In a few spots twigs and small branches had blown down, allowing us to examine canopy lichens. There was a fair amount of head-scratching over assorted Cladonia species, in corticolous, saxicolous and terricolous habitats, with Pete finding cool Cladonia caespiticia showing fruiting bodies on short stalks. Other terricolous Cladonia were the richly-branching C. portentosa, C. arbuscula and C. ciliata and there were a couple of sightings of the interesting Trapeliopsis pseudogranulosa overgrowing decaying moss and vegetation with orange and yellow-green granules.

On the way back to the car park there were a few hazel trees which yielded some alkaline bark species, not seen before. Hazels were notable for their absence in the Moss Mire area, perhaps because the rock, therefore soil, is acidic. However there was very little tree regeneration there of any species, or indeed herbaceous flora, which is a sure sign of heavy grazing and, long term, leads to the death of the woodland. This is very much in the news now – how best to regenerate oceanic woodland in the UK? Deer fencing can mean no browsing at all which some lichenologists dislike as tall ground flora and eventually saplings adversely affect lichens on trunks by shading them out. Alternatively a site could be managed for light grazing which allows some natural tree regeneration – but this means major deer culling and only a small number of livestock which could be an effort to monitor etc.

This was a great day with lots of lichen chat, skill sharing, looking and learning.

Caz Walker. Photos: Chris Cant, Pete Martin, Ann Lingard