Francis Rose visited Lowther Park in the early 1970s as part of his Cumbrian research. He describes “the park as a whole” being “quite one of the most interesting lichenologically in northern England, probably the richest so far discovered. This is due probably to its great age and the consequent presence of old trees which may well be directly derived from relics of former ancient woodland…”. In particular, he found Lobaria pulmonaria and Lobaria (now Ricasolia) amplissima on several trees.

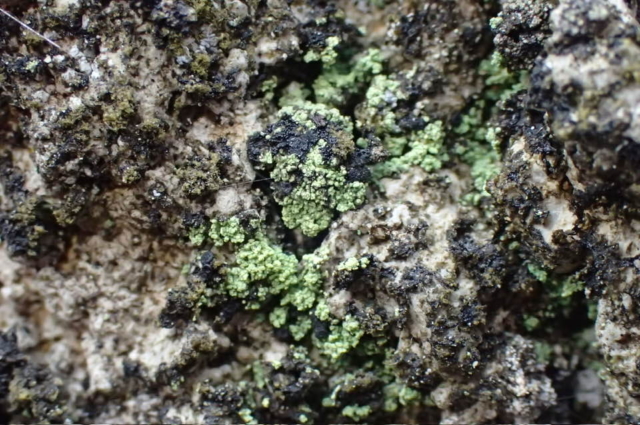

In 1980, one of those trees had to be felled for safety reasons, and Oliver Gilbert translocated a number of thalli of R. amplissima. He described this, and subsequent follow ups, in a series of articles in the Lichenologist: several of the translocations were doing well until at least 2000. Recent attempts to find them, however, have proved unsuccessful.

The Lowther Estate is currently moving towards less-intensive agriculture; it is part of a number of conservation/ rewilding initiatives. Together with Caz Walker and the estate ecologist Elizabeth Ogilvie I recently spent a day visiting the grid references for the Lobarion and other lichens of interest described by Francis Rose and Oliver Gilbert. What would we find? To be honest, my expectations were low. Previous visits had led me to expect a lichen flora heavily influenced by nitrogen pollution.

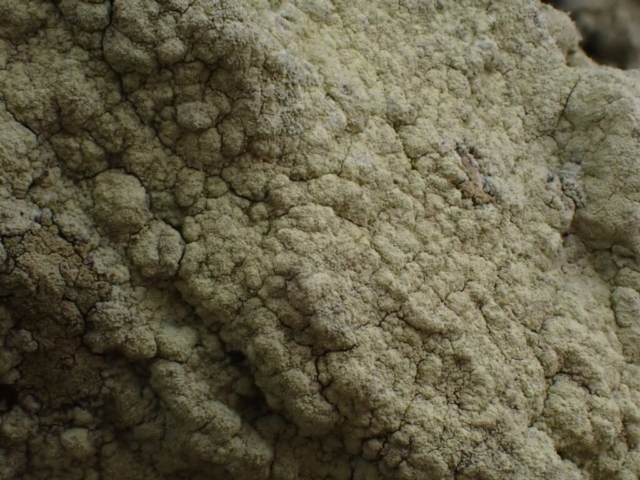

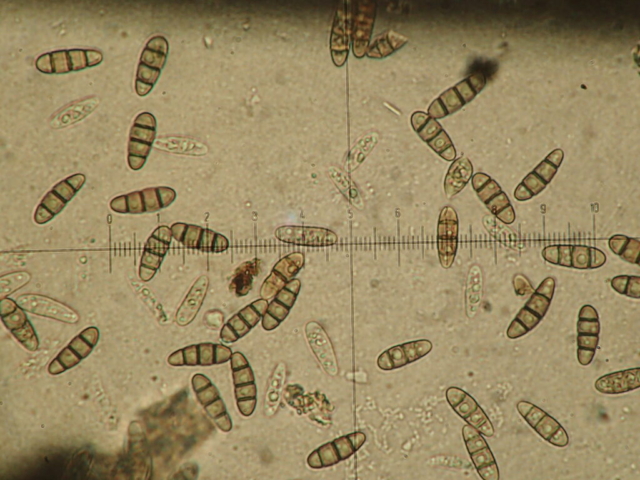

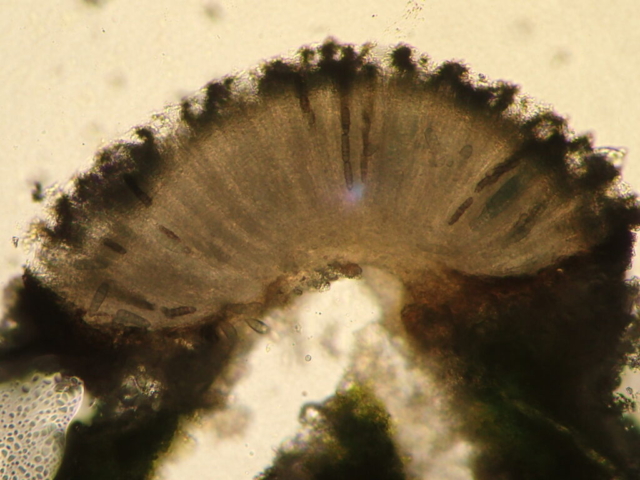

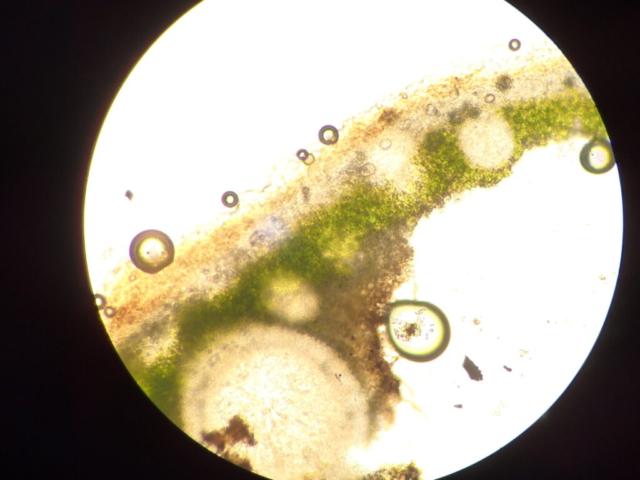

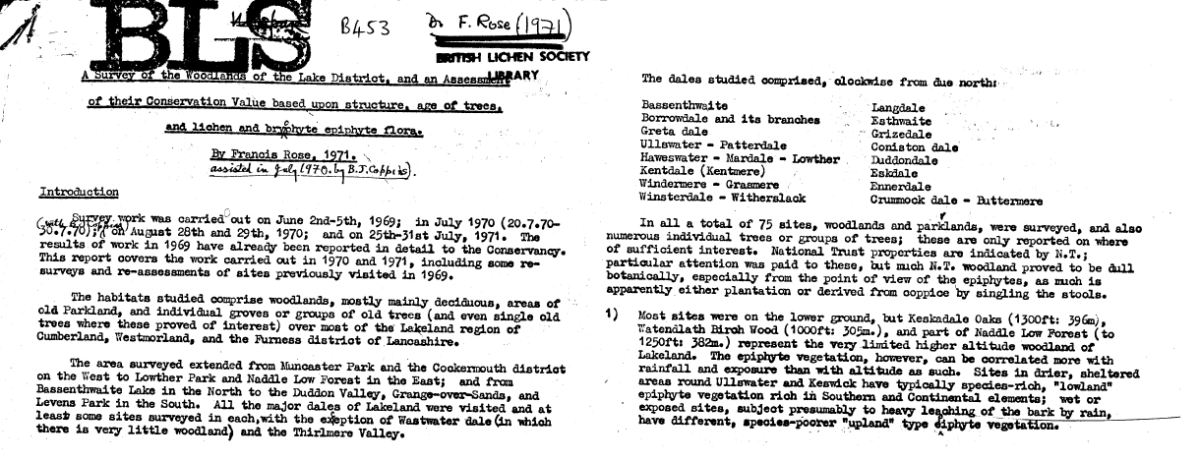

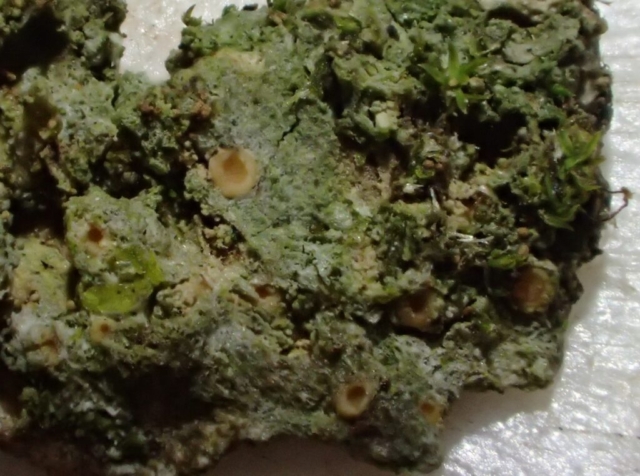

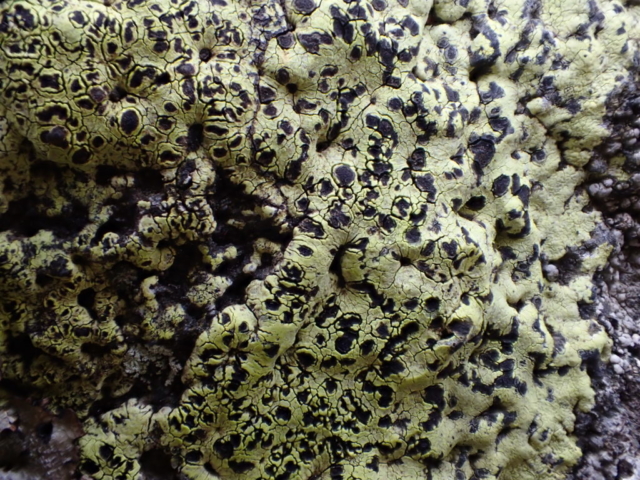

The first thing to say is that there are a lot of very nice trees at Lowther; many old oaks and others; some very old. And the second thing to say is that those trees often have a lot of lichens on them: the light, climate, longevity of habitat (and presumably air quality) has led to strong epiphytic lichen growth in the park. Many species are prolifically fertile/ sorediate/ isidiate.

However, we failed to find any evidence of Oliver Gilbert’s translocations surviving. Of the three trees on which translocations remained in 2000, one has been felled, one is now overgrown with ivy and the other, originally described as a mossy oak has become a very mossy oak, to the exclusion of almost all lichens. We also failed to find any non- translocated Lobaria pulmonaria or R. amplissima. We couldn’t find the six trees (at four sites) in the park: stumps suggested they had been felled. The trees in the wooded gorge area seemed suitably old for Lobaria pulmonaria (which in the 1970s was described as being “in plenty”). They have, however, become overgrown with ivy and further shaded by encroaching beech and conifer regeneration. Rhododendron is rampant; there has been little control until recently.

It wasn’t all bad news though. Some of the lichens mentioned by Francis Rose remain: a tree with Pertusaria flavida is highly visible from afar. Whilst we could not locate the tree he found Xanthoria ulophyllodes on, we located it on another oak a short distance away. Pertusaria coccodes, Parmelina tiliacea and Ochrolechia subviridis, all relatively uncommon in Cumbria, were found nearby.

For those of us more used to wet Lake District woodlands, it was nice to see Chrysothrix candelaris, Opegrapha vermicellifera and even Clisotomum griffithii. Pyrrhospora quernea was frequently fertile. There has obviously been a strong nitrogen influence on the lichen flora over many decades: X. ulophyllodes and P. tiliacea thrive on it. But there was less Xanthoria parietina and Physcia sp than we might have expected; less algal gunge than we had feared.

It was interesting to finally find out the fate of the transplants and Lobarion: the lichen flora of Lowther Park is now a shadow of the interest it was half a century ago. Before the visit I would have put the most important influence in that decline as being nitrogen pollution; now I would put it as loss of trees, and then allowing those trees to become shaded/ overgrown. There are lessons here for the management of parkland and the conservation of rare lichens.

There is much more of the Lowther estate to be visited; much more to be explored. It may be that there are areas of lichen interest in the more private woodlands (though Francis Rose stated that the parkland contained the greatest interest). So a further visit is not out of the question…but might not be top of the priority list.

Text and photos: Pete Martin 11.3.24