For our return visit to Kirkstone Pass, visiting expert Neil did say that some dampness would be nice and we were able to oblige with an hour or two of rain late morning after a cool start, with some late sunshine to start to dry us off. Standing in the beck to keep wet while looking at aquatic lichens was beyond the call of duty though.

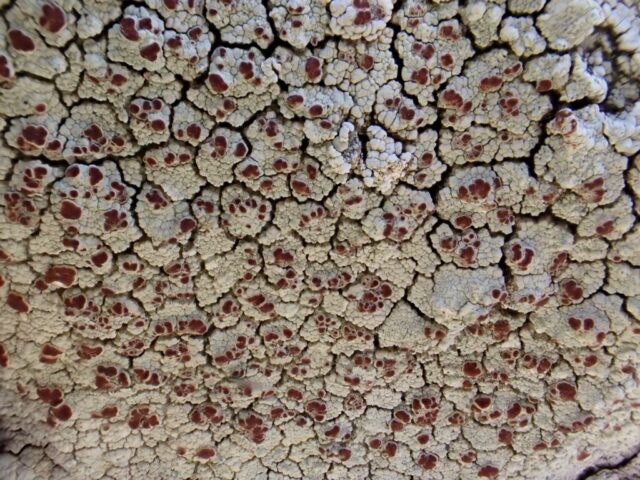

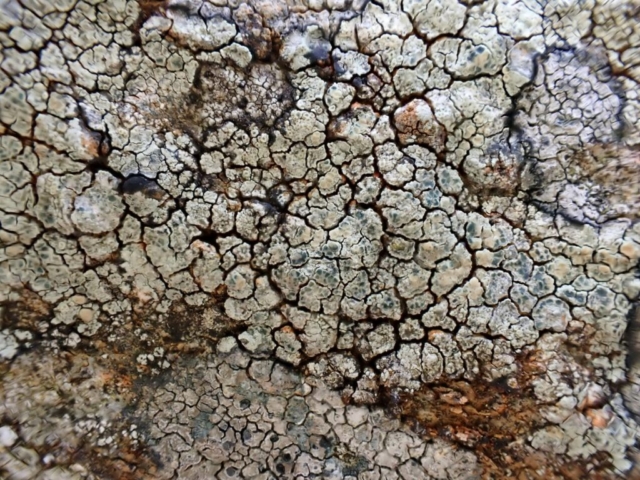

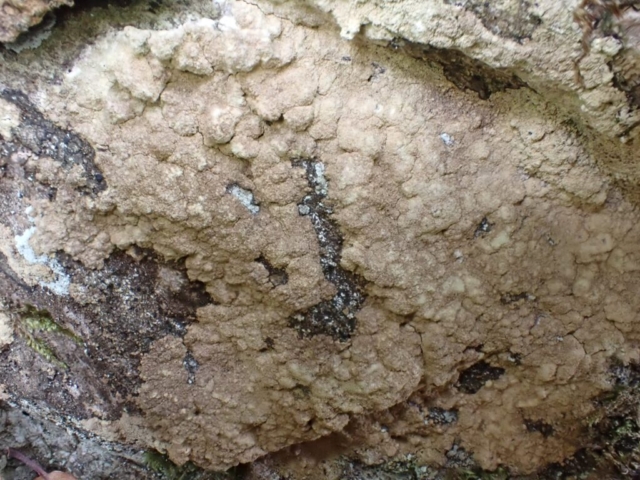

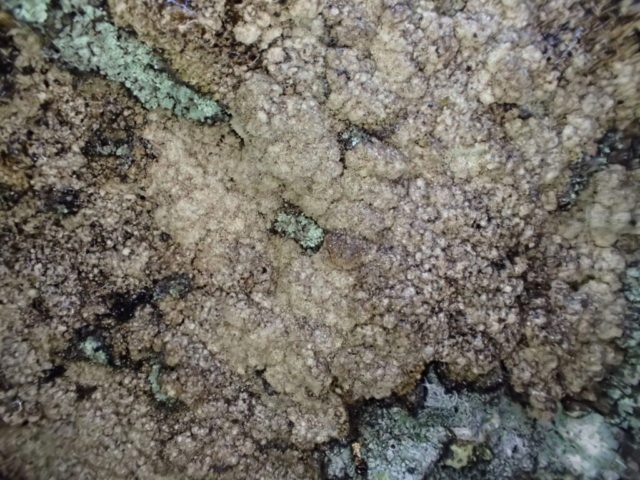

We were able to show Neil various saxicolous crusts while he helped us diagnose some trickier Cladonia species, with some exciting finds amidst the similar-looking basal squamules.

Kirkstone Pass is at roughly 450m above sea level. A recce to the east had not been very notable on steep ground so we headed west as we’d done on previous visits, trending left to the headwaters of Stock Ghyll above the Broad Stone and up to the base of Raven Crag at 579m. Every boulder was covered in crusts and the mossy outcrops featured Cladonia species. Neil astutely noticed another example of something we’d just seen – but it was placed there a few seconds before by Chris.

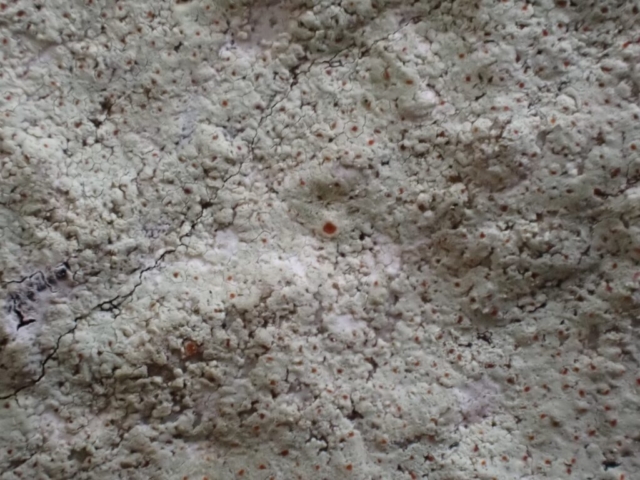

Neil’s star find was rare Cladonia pulvinata, Pd+ yellow, but he was also pleased to find Cladonia firma in several places, Pd+ orange.

There were several instances of Cladonia cyathomorpha whose large basal squamules have off-white-veined undersides, Pd+ red. Also present was Cladonia cryptochlorophaea, one of a difficult group of upland Cladonia, no doubt under recorded, KC+ fleetingly purple.

Neil found Cladonia crispata var. cetrariiformis, UV+ white, Pd-, which we may have mistaken for Cladonia furcata which is UV- and Pd+ red. The C. crispata has a hole in the (final) branch of the podetia giving a star-like effect looking down.

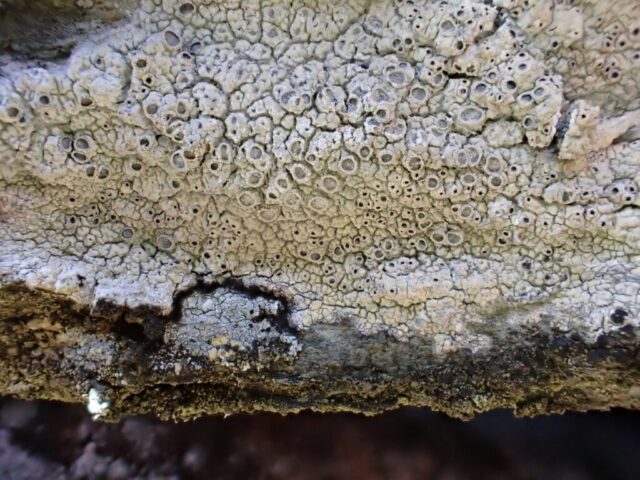

At the ghyll we refound several instances of Collema flaccidum and Dermatocarpon luridum, indicating a basic influence. Some small green squamules on a damp vertical rock face were Normandina acroglypta. On a frequently inundated rock in the beck was Staurothele fissa with projecting perithecia partially covered by thallus giving a bulging look. Another lichen on this rock turned out to be Catillaria chalybeia var. chalybeia, with a brown thallus when dry but green when wet. The thallus was thicker than normal, almost granular/squamulose, but the spores were right, the paraphyses had a brown cap, the lower hymenium was green and exciple solid black.

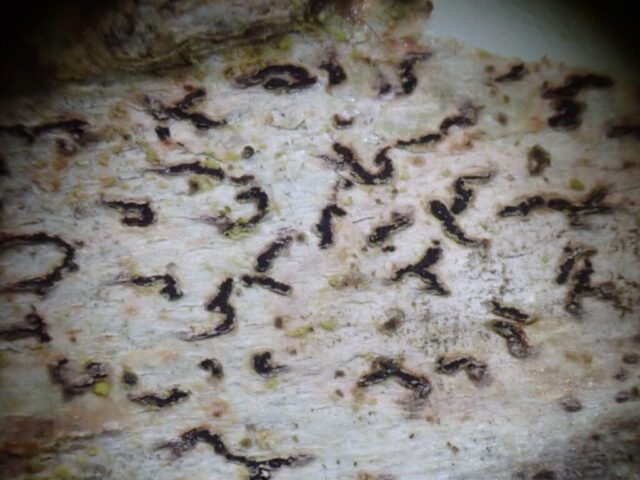

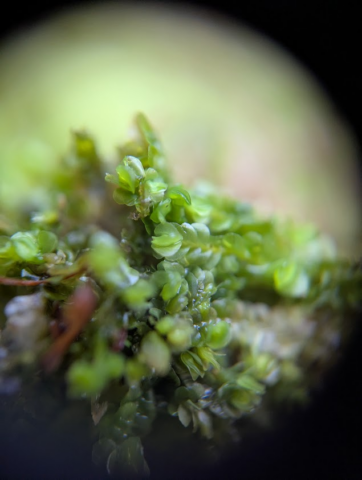

Heading up towards Raven Crag we found filamentous lichen Polychidium muscicola (with a few apothecia) contrasting nicely beside the more common Ephebe lanata. E lanata has dark green combed filaments made of Stigonema alongside hyphae and no cortex of fungal cells. This is compared to the darker cushions of P. muscicola with a cortex surrounding Nostoc and hyphae in the medulla. There was another patch of filaments which didn’t match a lichen so must be a cyanobacteria.

We would welcome any other peripatetic experts to drop in and share their wisdom, come rain or shine.

Text: Chris Cant

Photos: Chris Cant, Caz Walker, Neil Sanderson