Eleven months on, we returned to Tilberthwaite. Last time we visited the old mine workings, this time the woods were our destination.

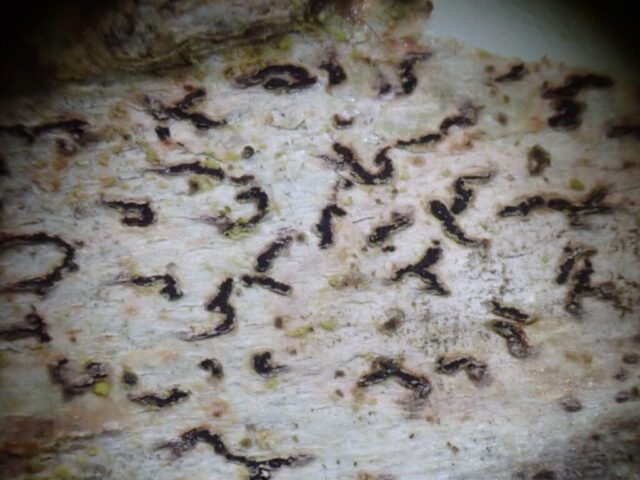

We made short work of the journey from the car park; the riverside had fewer Cladonia and Peltigera species than we were hoping for and didn’t detain us long. Immediately inside the gate of Low Coppice Wood was an Ash tree with some tiny Normandina pulchella squamules; Hazels had some Graphis species and Pertusaria leioplaca.

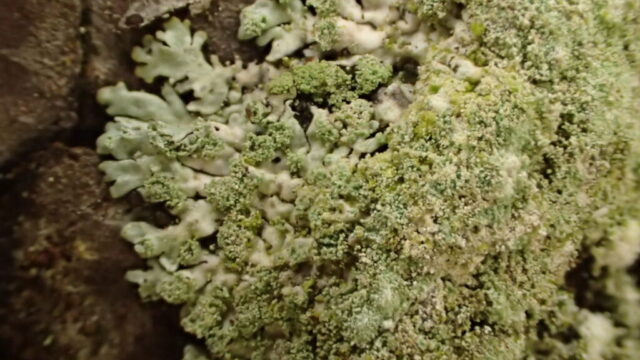

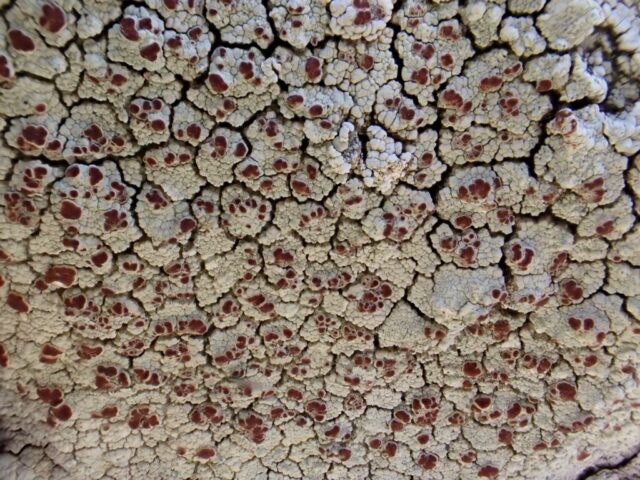

Then it was onto a steep slope, to look at Birches and Oaks. The trunks had Parmelia saxatilis, in varying sizes, and some Cladonia species. But little else until we were quite a way up the slope- or for some of us up and down and up the slope again: blame falling bags and a liking for shallow gradients. Once up on the low ridge, things became easier, and the lichens more interesting. There was Flavoparmelia caperata, apple-green and easily recognised, and Sphaerophorous globosus, a coral lichen with the distinctive growth form of a large, often brownish, central stem. Ochrolechia androgyna, a white crust with greenish soredia, formed large patches on trunks. There was also Hypotrachyna laevigata, an indicator of good wet acid-barked trees, with its beautiful smooth lobes, blob-on-the-lobe-ends soredia and little tree-like rhizines.

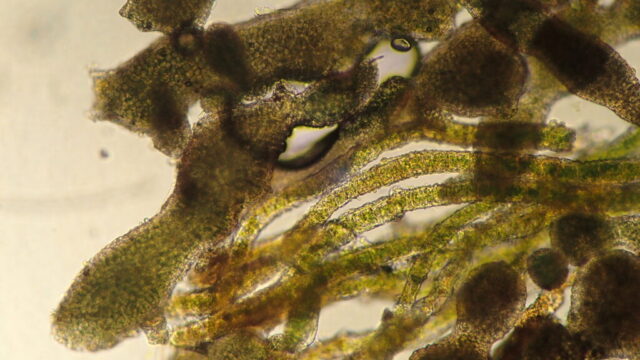

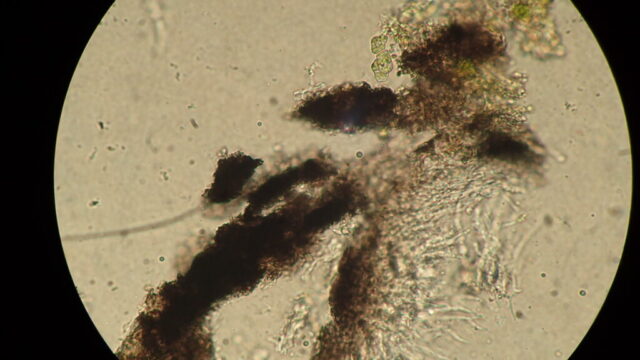

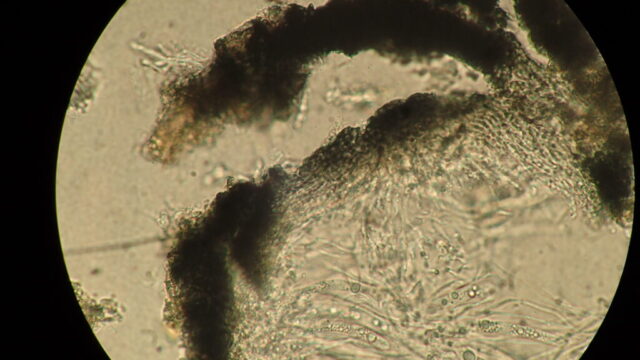

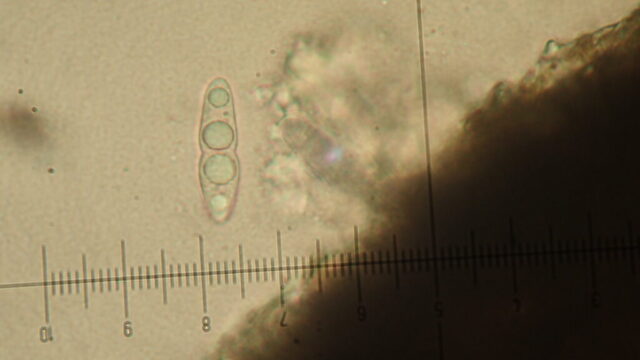

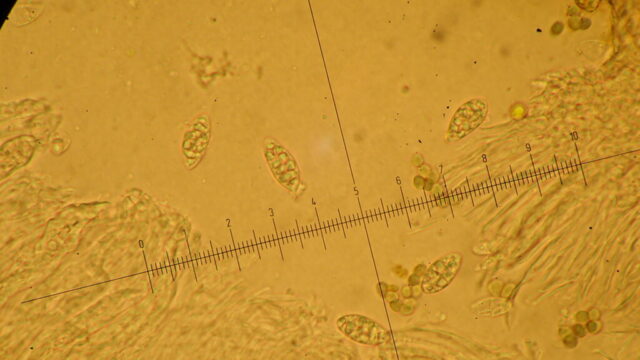

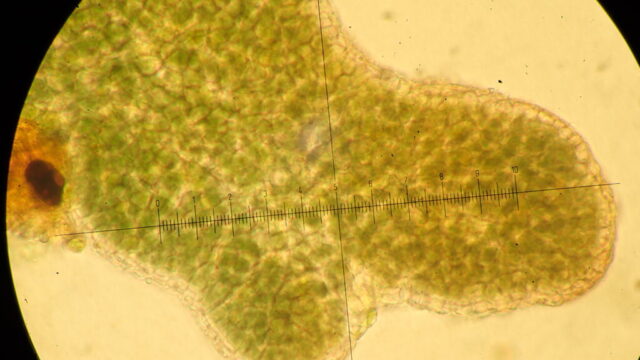

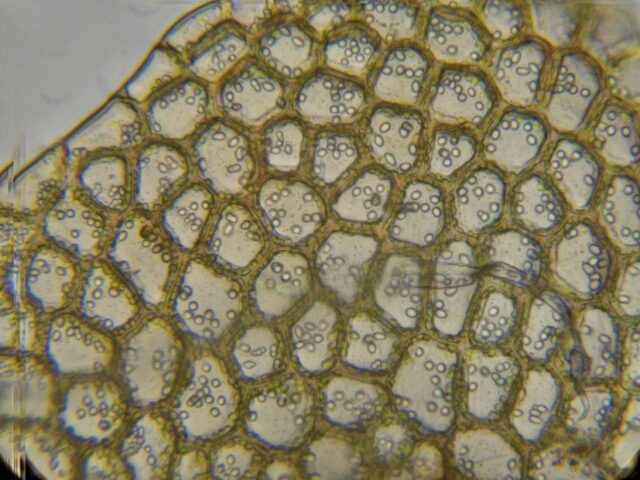

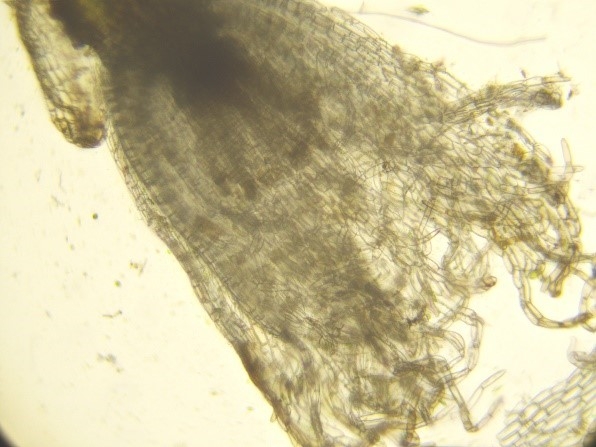

The first black apothecia I found were from Micarea lignaria: globose on a grey crust. But the next ones caused some discussion: they were on a greeny thallus overgrowing moss and were, at times definitely disc-like with a concolorous margin. Lopadium disciforme was thought to be unlikely; the margins weren’t right for Megalaria pulverea. Once home, the microscope soon showed what I was looking at: how could I have forgotten Bryobilimbia sanguineoatra? The apothecial sections have a lovely reddy-brown colour, with particles that go greeny in K.

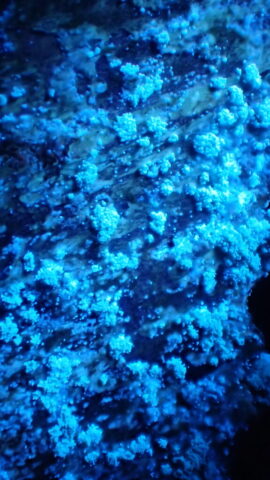

Next up was Cetrelia olivetorum s.lat, a big leafy lichen with white pseudocyphellae (specks) and soredia. Another indicator of old woodland, this was a bit of a scrappy example, but added to the feeling that this was a good wood. The ultraviolet torch gave a distinct blue fluorescence on the flecks and the soredia, indicating that this was C. cetrarioides, by far the most common species in the aggregate. Coming down the other side of the mound we ran into some Hazels. These had the small arthonioid apothecia of Coniocarpon cuspidans (which used to be known as Arthonia elegans) and more Graphis species.

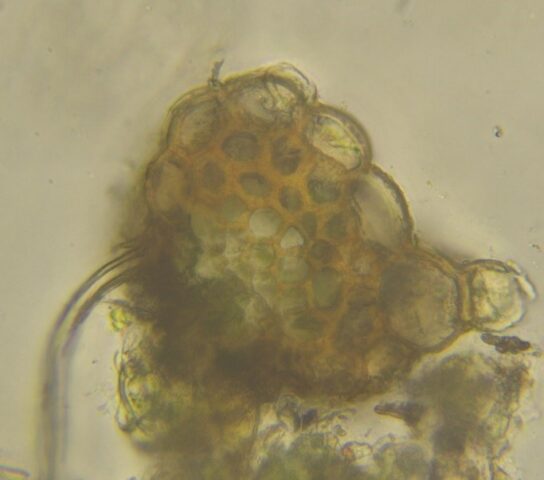

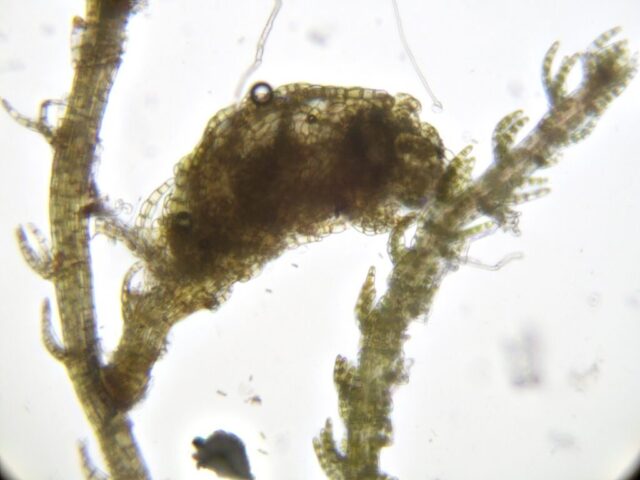

But it was time for another ascent of the slope, to visit the Bunodophoron melanocarpum colony. It has slightly flattened lobes compared to the other coral lichens and a different jointing pattern. So it can look as though little hands (or feet) are waving their fingers (or toes) at you. The fruiting bodies- and in this case it is a fertile colony- are really something special: grey horn-of-plenty trumpets with a black smudgy spore mass at the end. The colony measured getting on for 2m by 1m and is the only known one in the Windermere and Coniston catchments. Just below it, Caz found fertile Lichenomphalia ericetorum, a basidiomycete – with mushroom-like fruiting bodies just starting to grow. The same birch also had Lepraria membranacea, a powdery crust which forms lobe shapes round the edge. We descended the slope, and lunched.

After some discussion, we headed north, through an area of Larch that has so far evaded Ramorum felling. This had a different flora: lots of Hypogymnia physodes and a buff-coloured taxa we think might be Chrysothrix flavorirens. There was a little Usnea subfloridana and Bryoria fuscescens on one tree: in the South Lakes the felling of the Larches is removing the main habitat for Bryoria as a corticolous species.

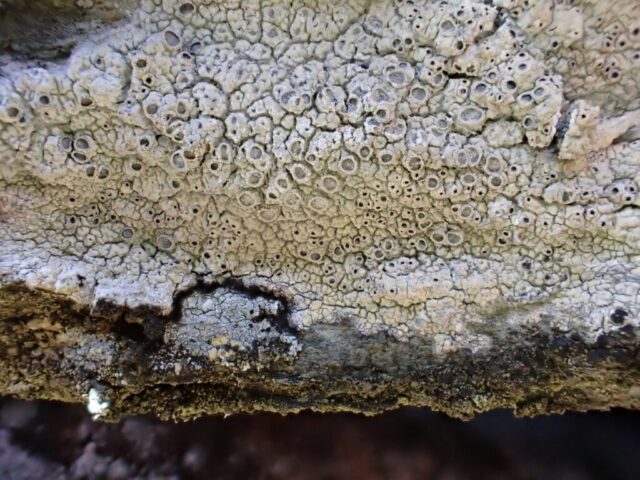

Leaving the wood by a stile, we were detained by a couple of good old Oaks. There was bitter-tasting Lepra amara, and also L. albescens; one of the trees boasted Mycoblastus sanguinarius, Ochrolechia androgyna and Sphaerophorous globosus. I thought at the time it also had Ochroclechia tartarea, but close examination of a photo suggests there may well be soredia present in small quantities, so now I’m not so sure.

We made a brief entry into a second woodland: open access land on the map but with a “Private Keep Out” sign on the gate. New species for the day included Ramalina farinacea and R. fastigiata, Melanohalea exasperata with its white-tipped papillae and Stenocybe septata on an old Holly. Huge boulders called out for investigation, but it started raining and the day was getting on. So we turned around and made our way back to the cars (via, of course, a quick up and down on the flank of the slope). The bryologists had also had a good day and found some Atlantic species, so whilst Low Coppice Wood may not be the biggest, or contain the most species indicative of wet acid-barked woodland, it’s certainly a pretty decent example for South Lakeland.

Text: Pete Martin

Photos: Pete Martin, Chris Cant, Caz Walker