We seem to be making a habit of exploring borderlands, this time again at the Cumbria-Yorkshire boundary in the uplands to the south east of Kirkby Stephen: Lamps Moss, south of Nine Standards Rigg. It’s an interesting spot with both acidic peat hag habitat and gritstone rock adjacent to limestone pavement and sinkholes. As a result we saw a good selection of lichens which prefer these different niches. The site is part of the Mallerstang-Swaledale SSSI.

At over 500m this is an exposed site so the trip was nearly cancelled due to ongoing stormy weather. However a window of dryness after a later than usual start time meant we avoided the rain.

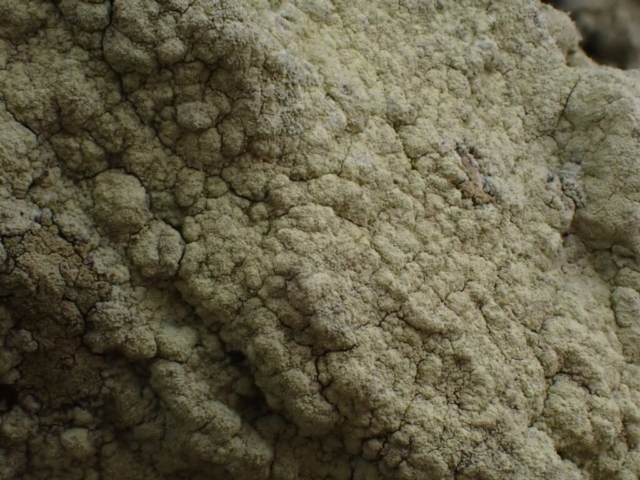

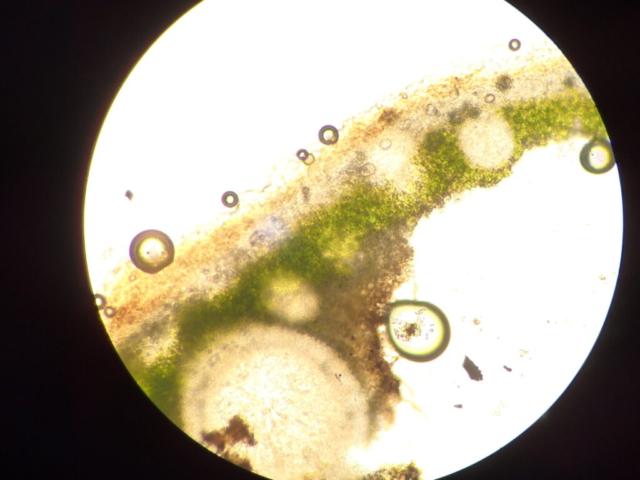

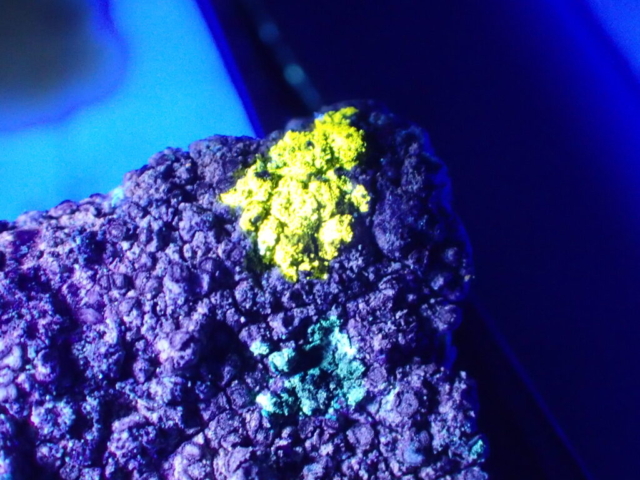

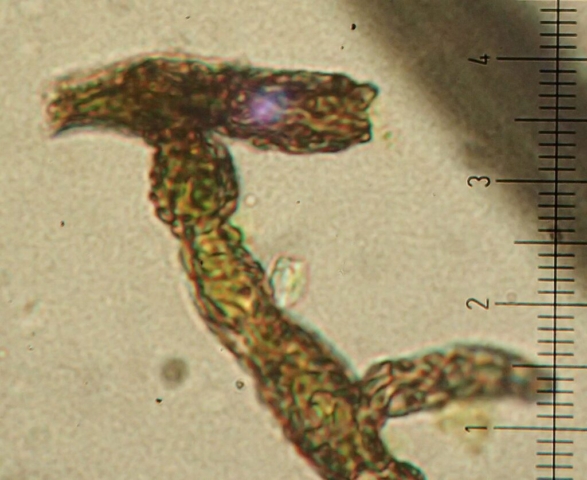

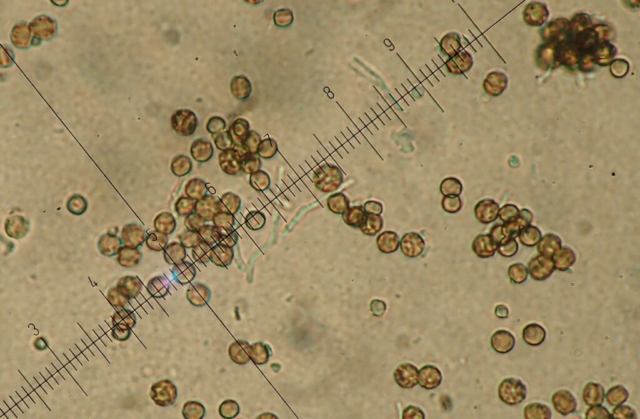

First we looked at the peat hags north of the road, commenting about the lack of lichens in the sward – not even much Cladonia portentosa was to be had. Dwarf shrubs such as heather, bilberry, crowberry and cranberry were there, however, so past management might be the explanation. However, on low exposed peat banks there was a range of Cladonia species – red-fruited C bellidiflora and C diversa, brown-fruited C ramulosa and spiky C furcata. The basal squamules of Lichenomphalia hudsoniana and the gelatinous green thalline bobbles of L umbellifera (now L ericetorum) were here too. A fuzz of yellow-brown granules on horizontal peat seemed a candidate for Placynthiella dasaea and a specimen was taken to torture once it had dried out – applying chemicals to sodden lichens doesn’t work. It turned out to be C+red with green algae of the right size, hopefully confirming it as P dasaea.

There have been attempts to restore some of the areas of bare peat by blocking channels and spreading cut heather on unvegetated ground – this may help mosses but will kill any lichens growing here and indeed very little was seen at these spots.

A long-discarded crisp bag deep in the Sphagnum turned out to be a sexton beetle graveyard where maybe 30 of them had been attracted to their deaths by the strong smell of earlier rotting beetles.

We went back to the carpark for lunch and to meet further participants. This allowed for the examination of several concrete posts which had a good covering of crustose and a few foliose lichens, including unusually fertile Physcia caesia.

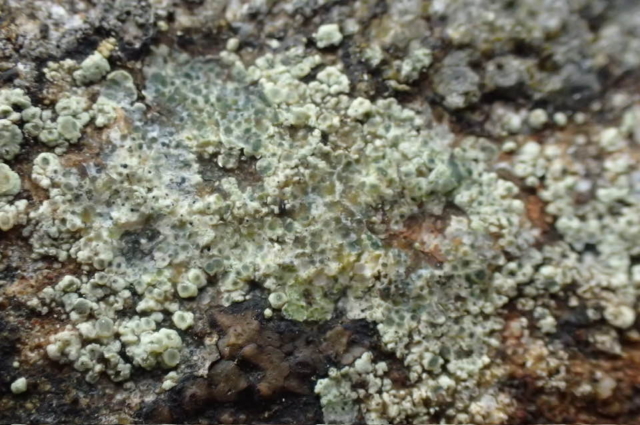

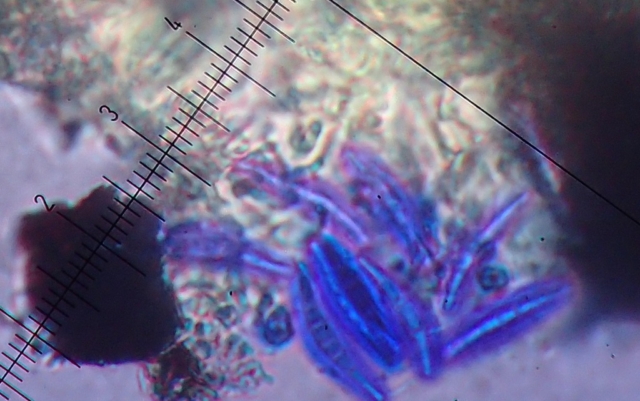

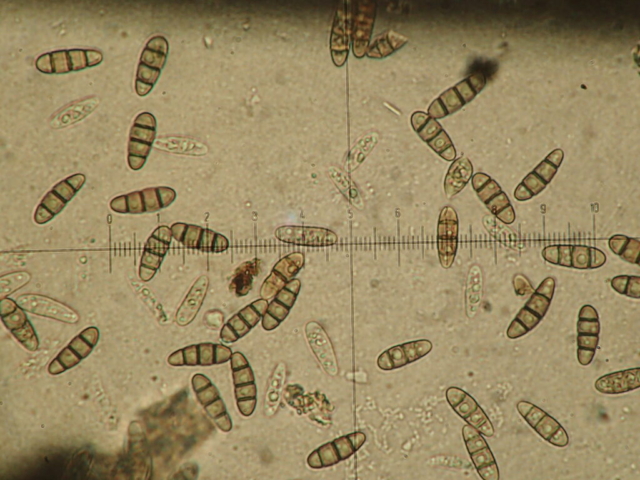

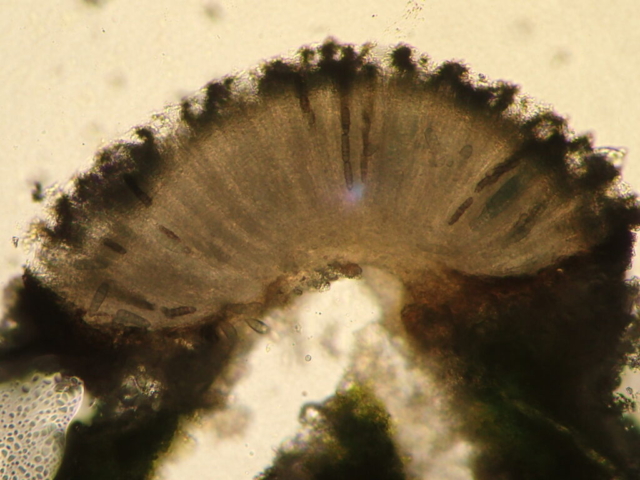

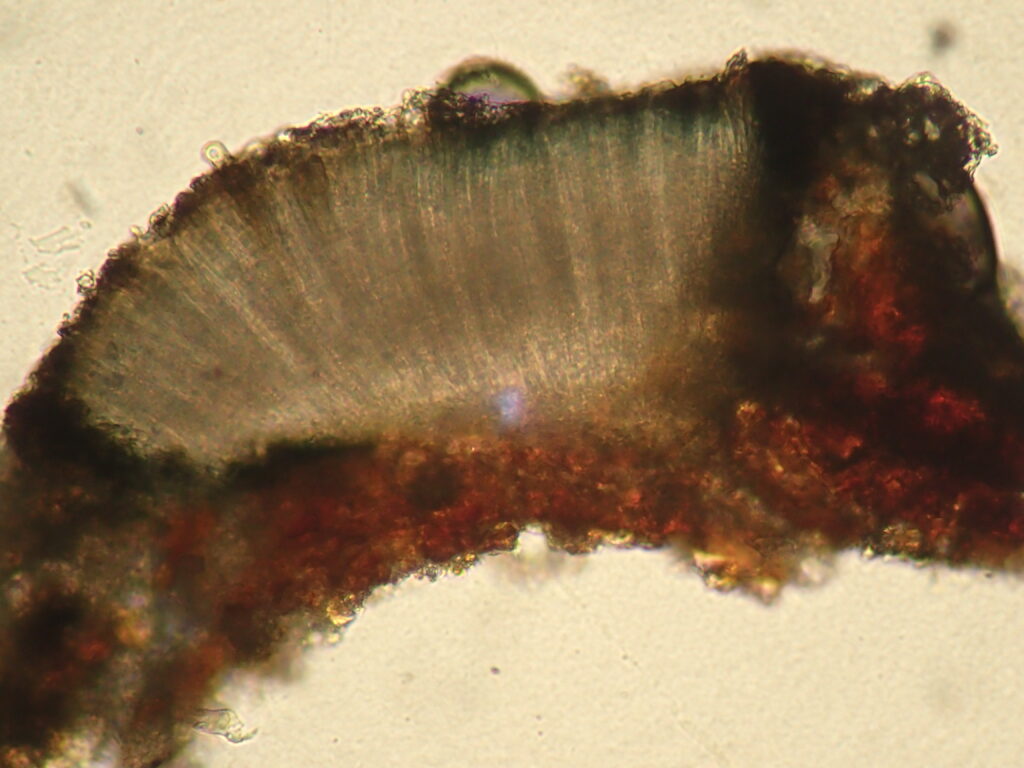

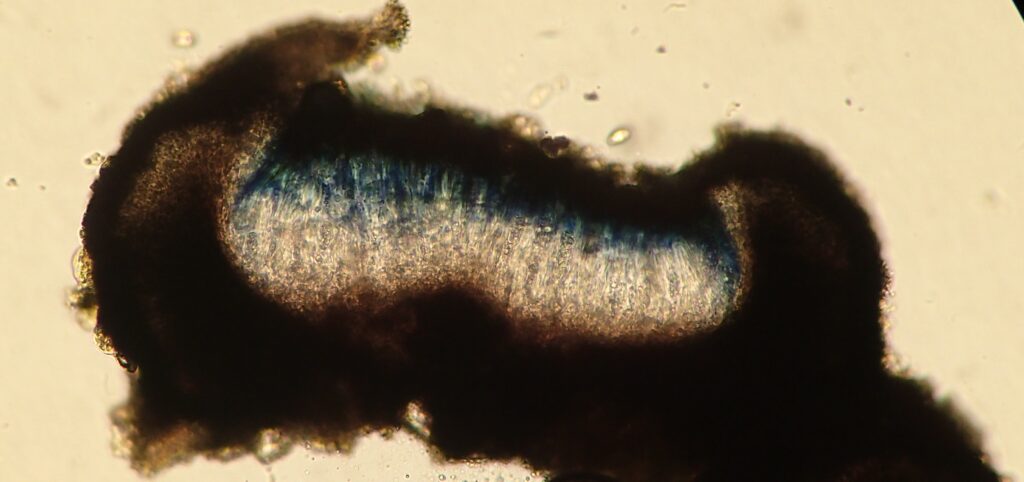

A short walk further west took us into the next monad where we looked at terricolous and saxicolous lichens on limestone. There was green Peltigera leucophlebia dotted with brown cephalodia, P polydactylon with brown veins on the underside that come to the lobe edge and P canina showing bushy, confluent rhizines beneath. The intriguing Diploschistes muscorum was consuming a Cladonia victim nearby by overgrowing it and pinching its algae. The star find on limestone was Sagiolechia protuberans, a rare species with 4 previous records in Cumbria. This had black star-shaped apothecia on a slightly orange thallus. Nearby there were the immersed pink apothecia of Hymenelia prevostii (green alga so the thallus scratches green) and further on Hymenelia epulotica (Trentepohlia as photobiont so scratches yellow/orange). Other good finds included Solorina saccata amongst moss in a sheltered sinkhole, Bryobilimbia hypnorum and Arthonia calcarea, as well as the usual suspects Gyalecta jenensis (now Secoliga jenensis), Protoblastenia rupestris and P incrustans plus assorted jelly lichens. Pete had a specimen which may turn out to be a Staurothele species – tbc.

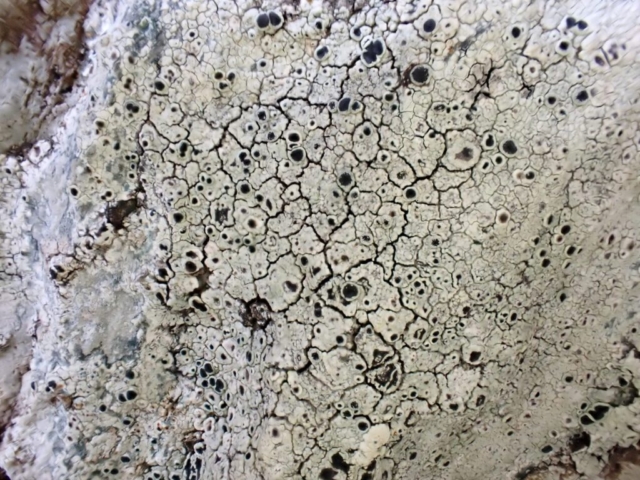

Before driving off, Judith found a beautiful Lecanora intricata with wrinkled areoles and flexuose apothecial margins on the sandstone capstone of the YDNP sign by the road.

Text: Caz Walker

Photos: Chris Cant, Pete Martin, Judith Allinson