Lichens

It seems to be an annual occurrence now: to have a field trip during very hot dry weather. A couple of attendees had sensibly dropped out in advance. We started off in the open on the limestone at the edge of Little Asby Scar, but retreated into the shade of the hawthorns next to Sunbiggin Tarn until we boiled off at 3pm.

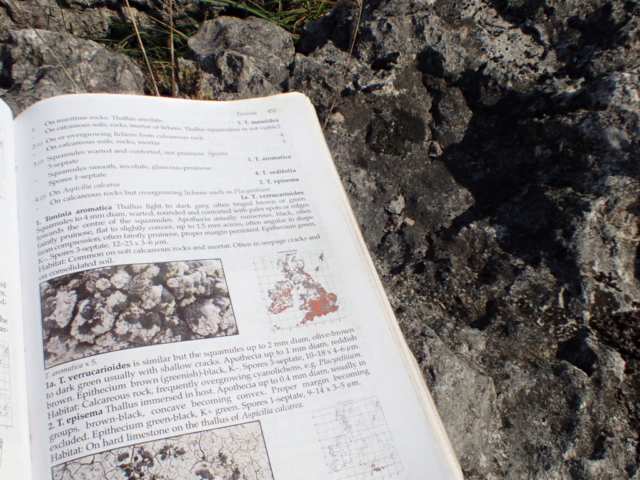

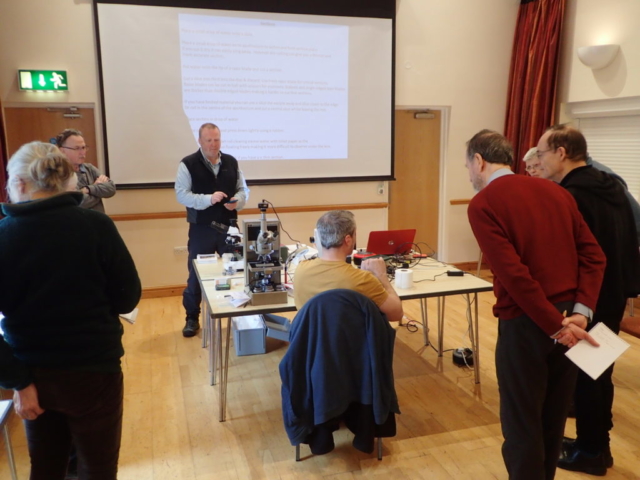

The day was one of a series of events in August to celebrate the life of Frank Dobson who died in December 2021. He wrote several lichen books including the essential “Lichens: An Illustrated Guide to the British and Irish Species” now in its seventh edition in 2018. This is a vital part of any lichen outing with keys and information on morphology and chemistry to help identify lichens in the field and when back at base eg using microscopes. On this trip, we had three “Dobsons” on the go at one point trying to work out an id. The British Lichen Society (BLS) will be updating this guide book in due course, no doubt including recent taxonomic changes.

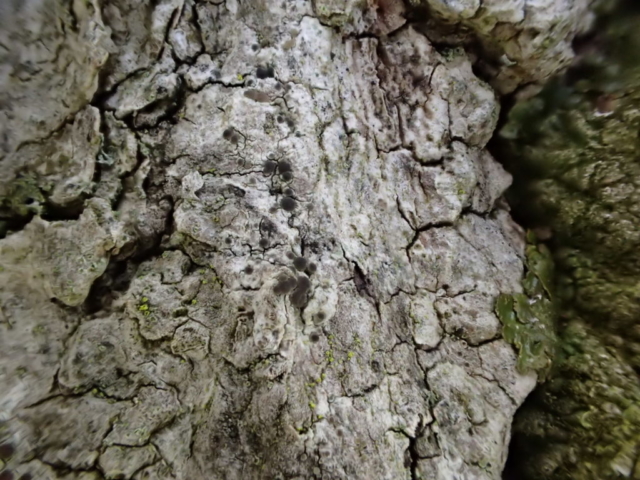

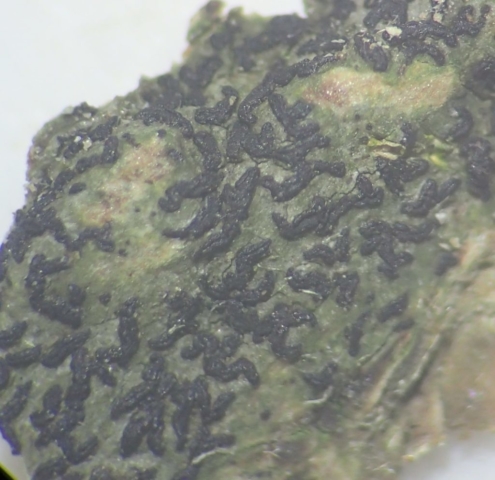

The limestone had some nice usual suspects such as Caloplaca flavescens, Dermatocarpon miniatum, Placynthium nigrum, Protoblastenia rupestris and Squamarina cartilaginea. We spent some time on a Lecanora but didn’t come to a conclusion.

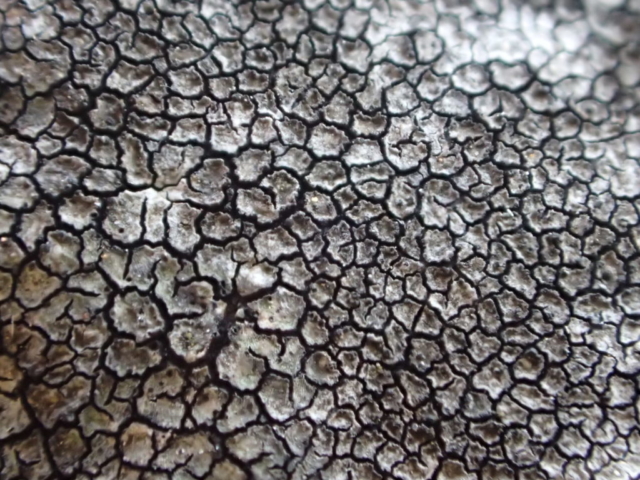

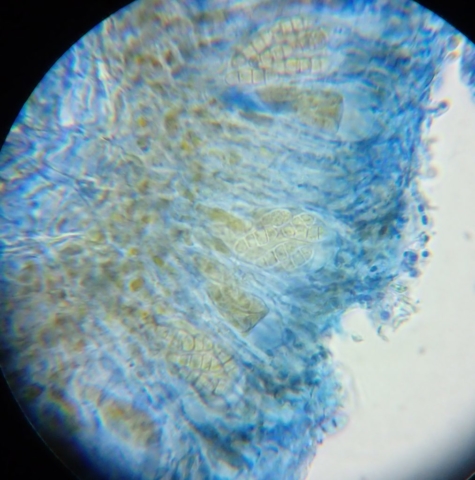

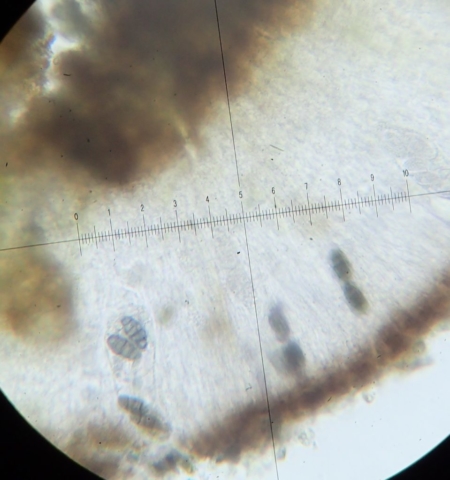

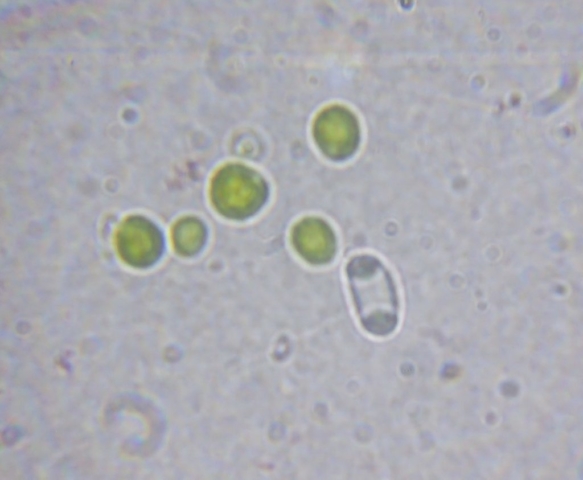

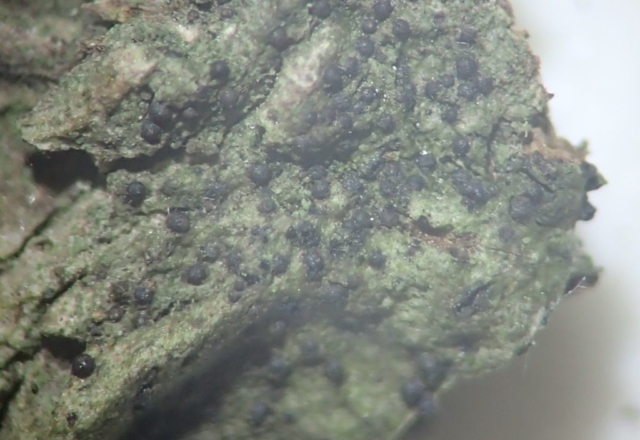

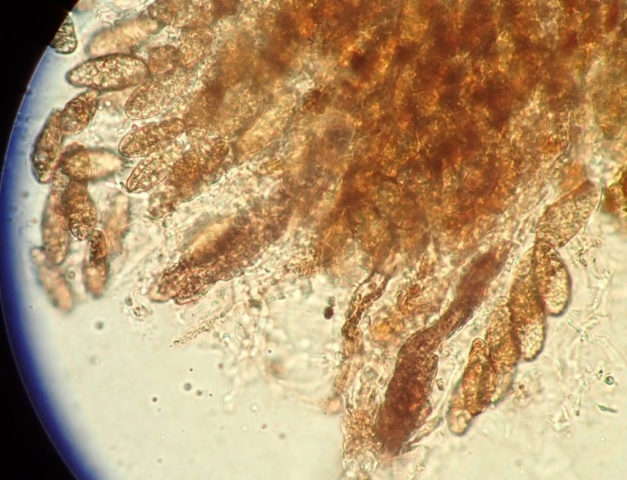

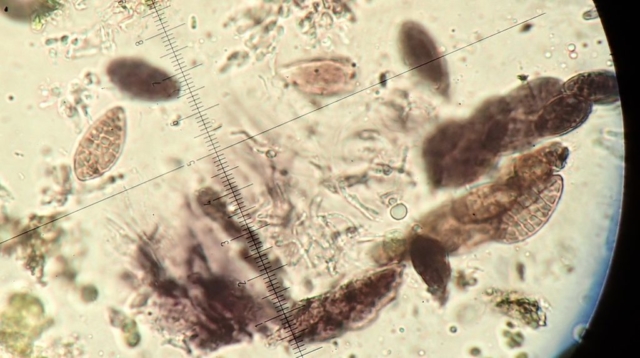

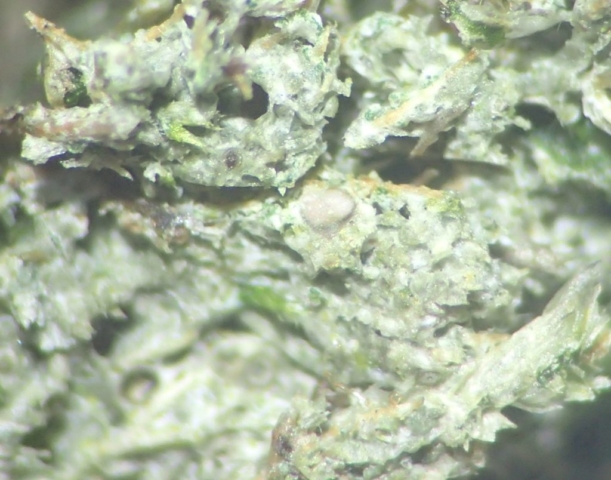

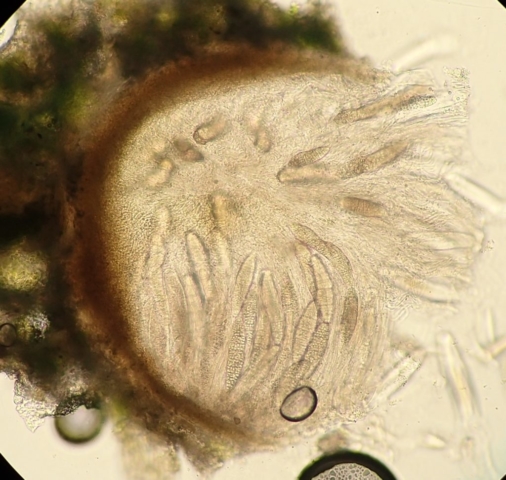

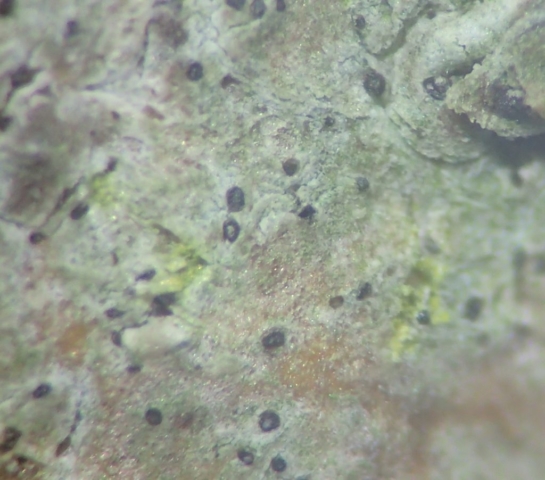

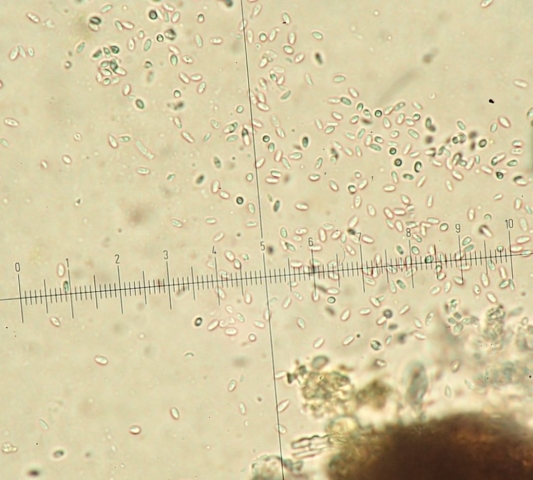

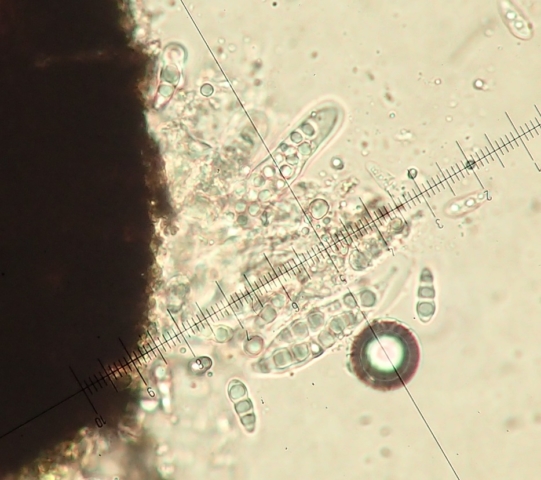

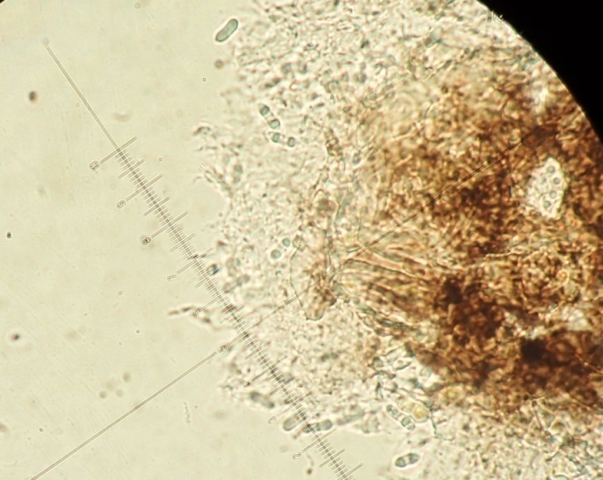

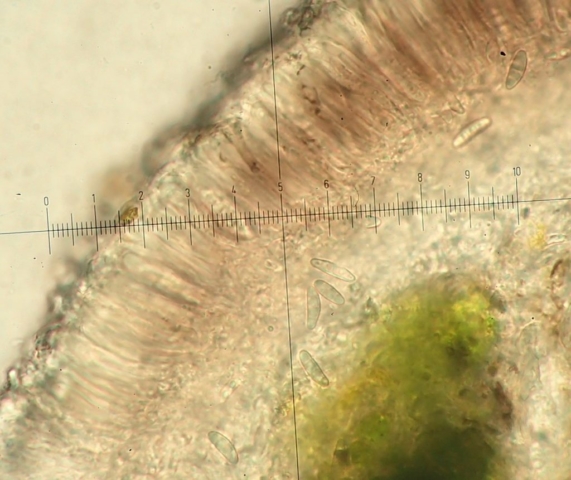

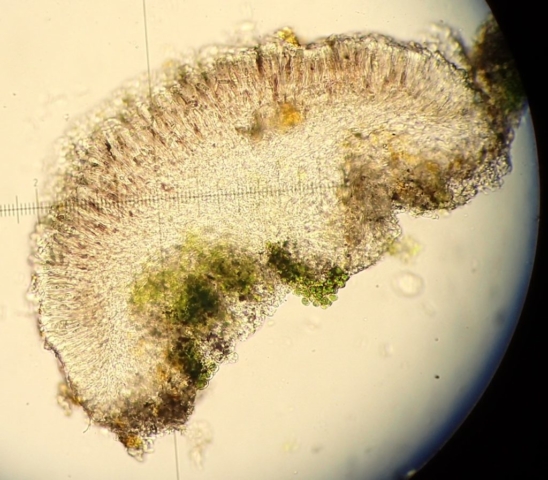

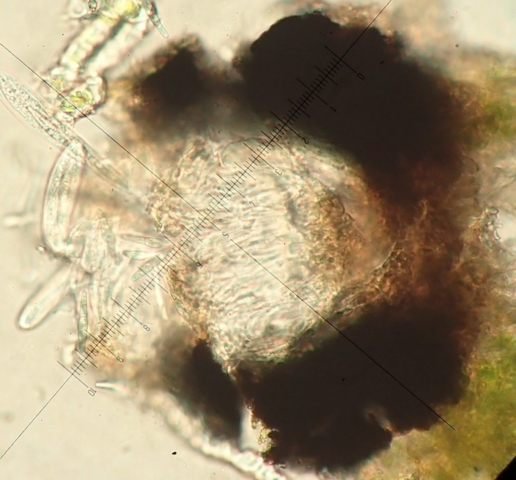

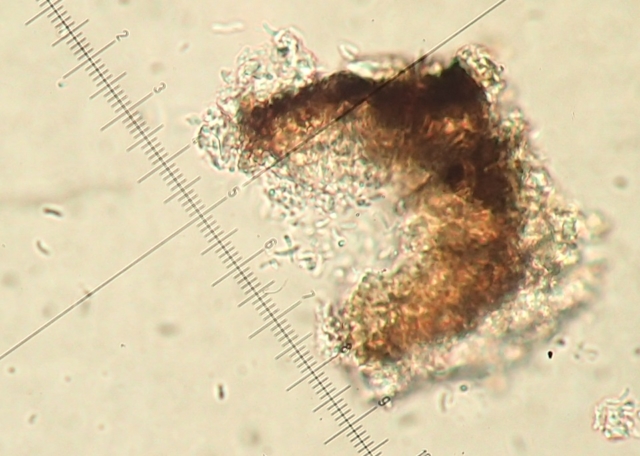

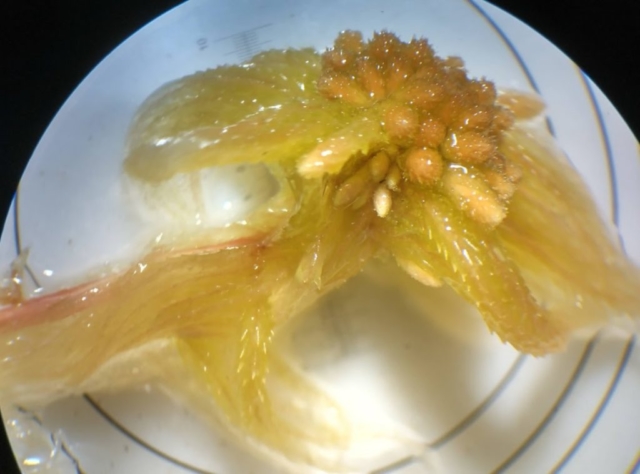

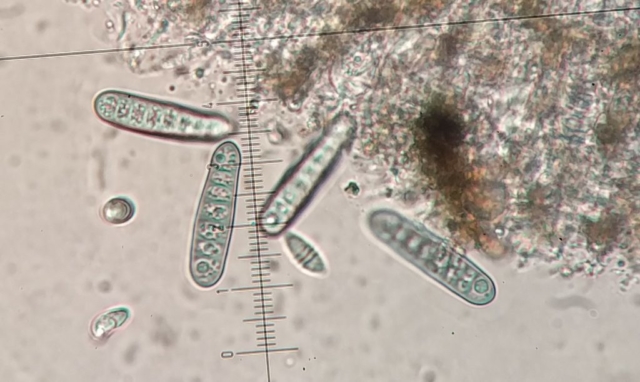

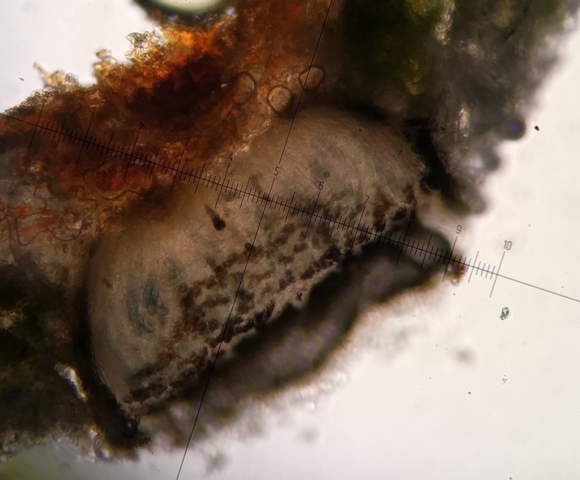

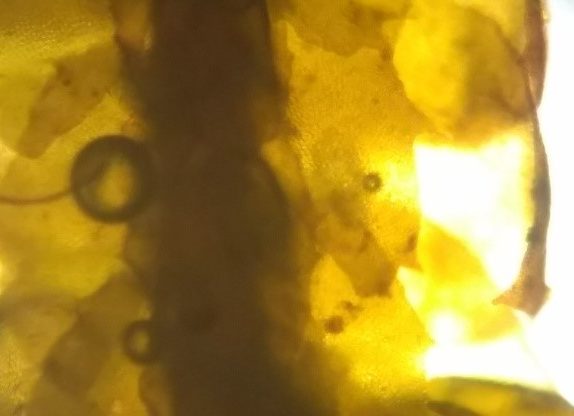

Sue found some perithecia with a black on white cracked crust, which she recognised as potentially being Acrocordia conoidea. Back at base, Chris and Caz eventually concluded that it must be a Verrucaria as it had simple spores that weren’t uniseriate in the ascus – and keyed out a tentative species identification, but the experts we consulted weren’t convinced. Verrucaria species can be tricky to identify, especially where there’s a crust of algae or cyanobacteria on top, as in this case.

Near the tarn, we found some shade for lunch behind a dry-stone wall which sported some more lichens for id. After that we moved to the nearby hawthorns which can be a good habitat for lichens, though the thorns do make it harder to look. There were a couple of instances of the large Ramalina fraxinea along with the more common R. fastigiata and R. farinacea, along with similar looking Evernia prunastri. It was good to hide in the shade, using Dobson to key out some species.

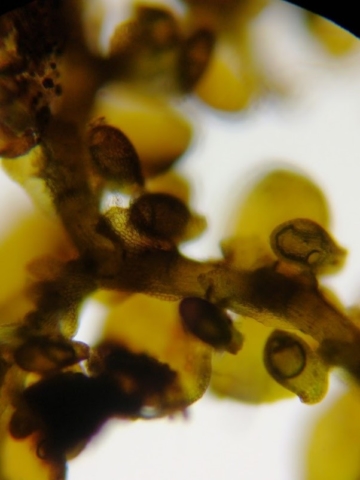

Nearby there was some earthy limestone with some Cladonia species on the edge of the rocks. We saw Toninia verrucarioides growing on top of Placynthium nigrum, along with a dry Leptogium pulvinatum.

We ended up with almost 50 species identified. It is always a pleasure to share a lichen enthusiasm with others in the field.

Text and photos: Chris Cant

Bryophytes

I didn’t have very high hopes of the outing to Sunbiggin Tarn. The forecast was for another very hot day, and although there had been some rain a few days before, it seemed likely that the bryophytes would be dry and tightly curled against the heat. However, four of us had braved the hot conditions and it was good to meet up and to be outdoors.

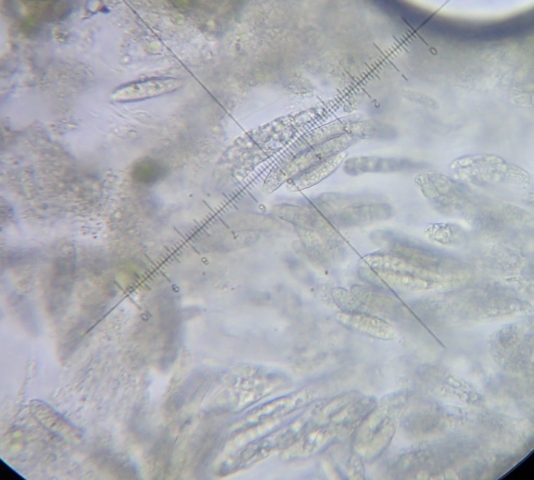

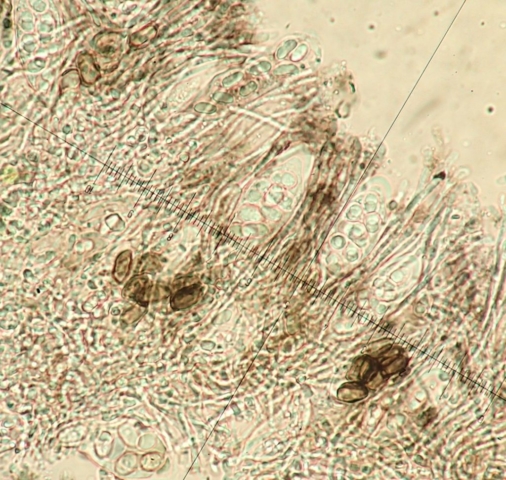

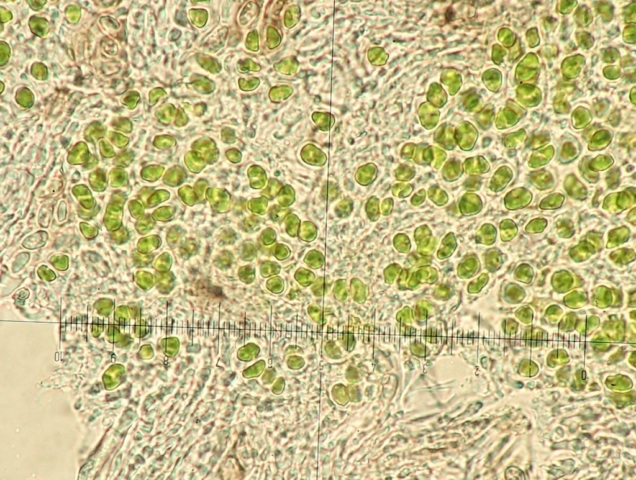

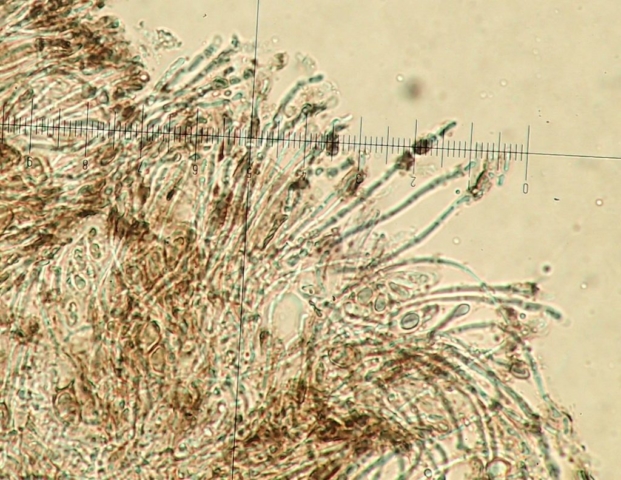

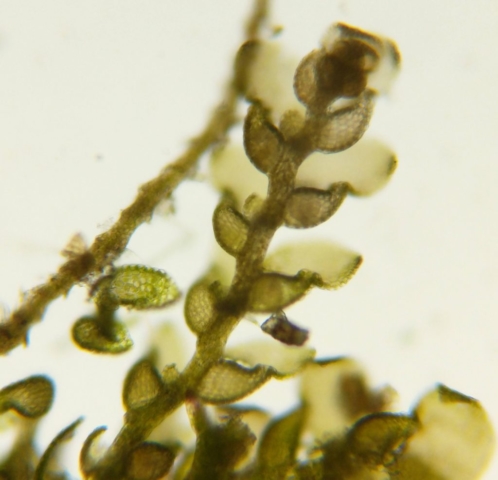

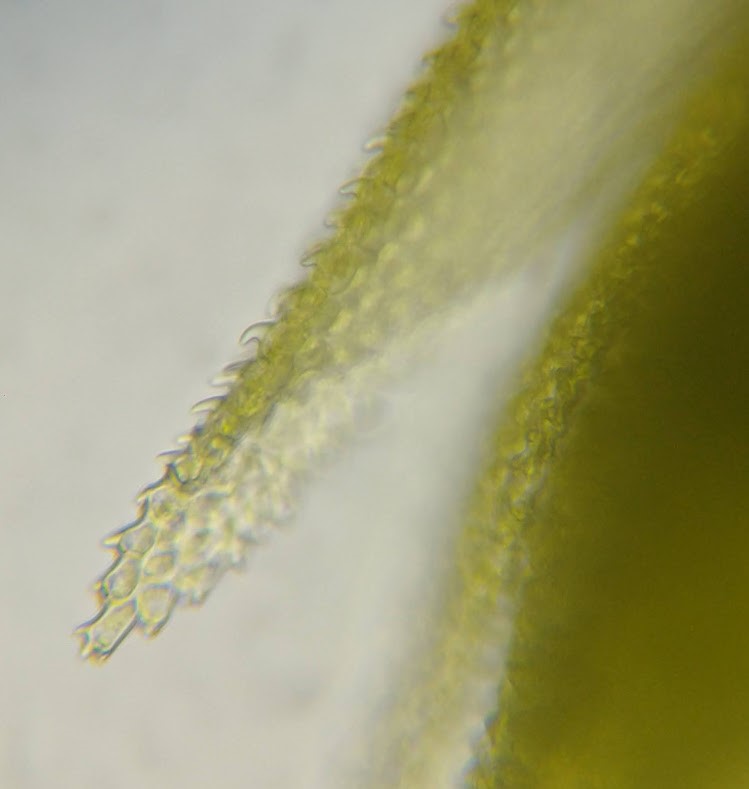

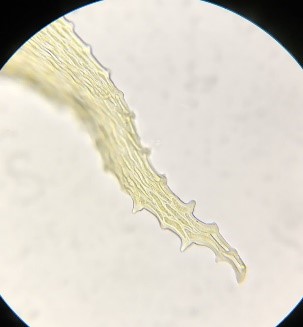

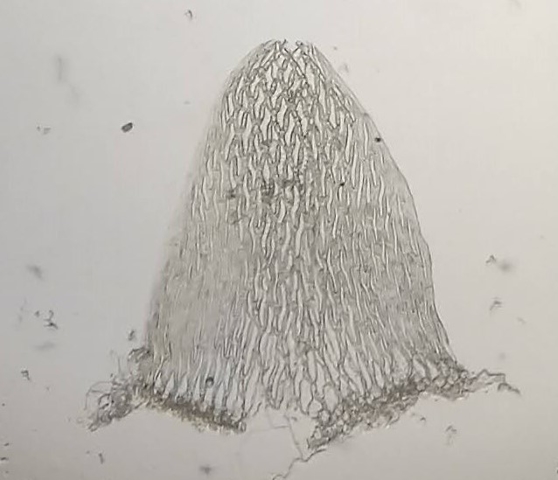

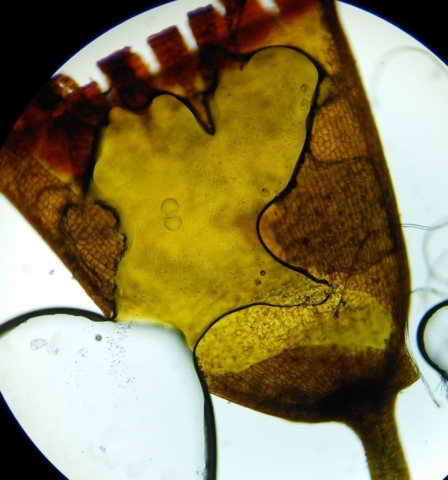

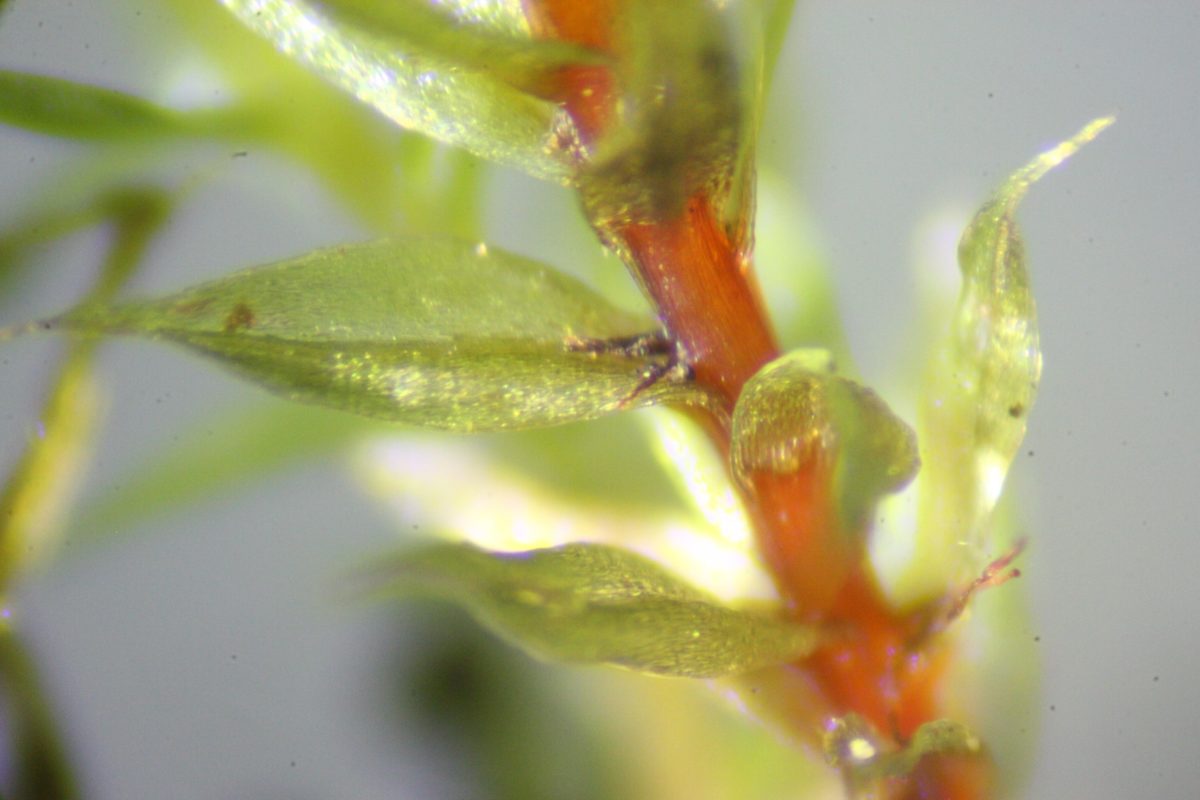

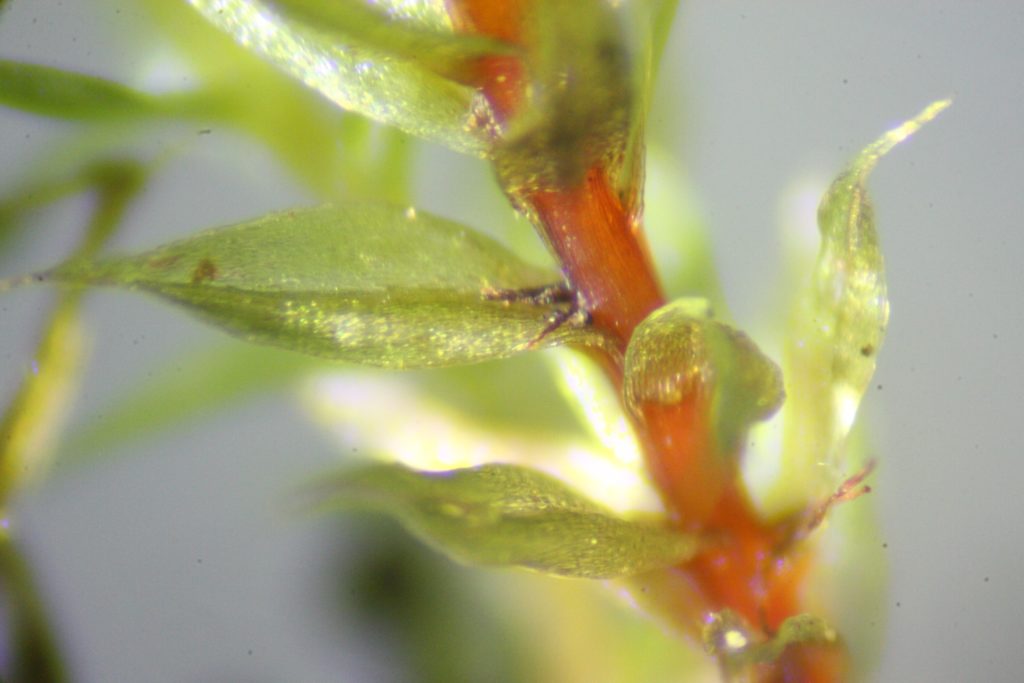

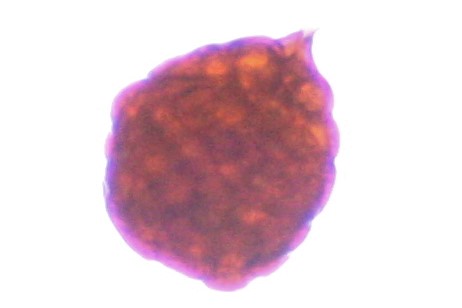

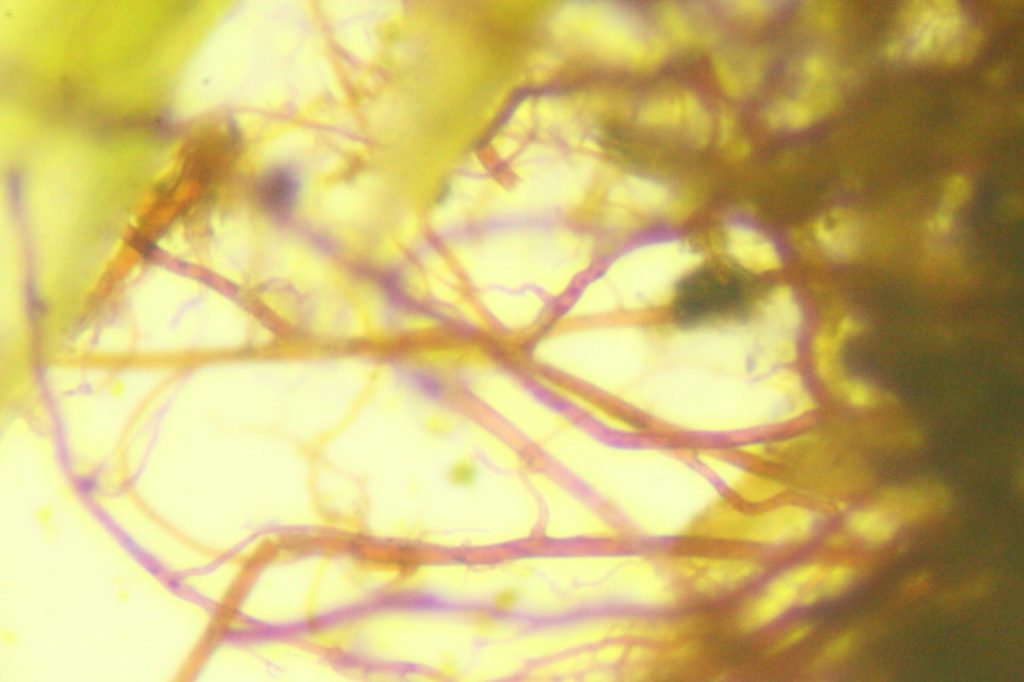

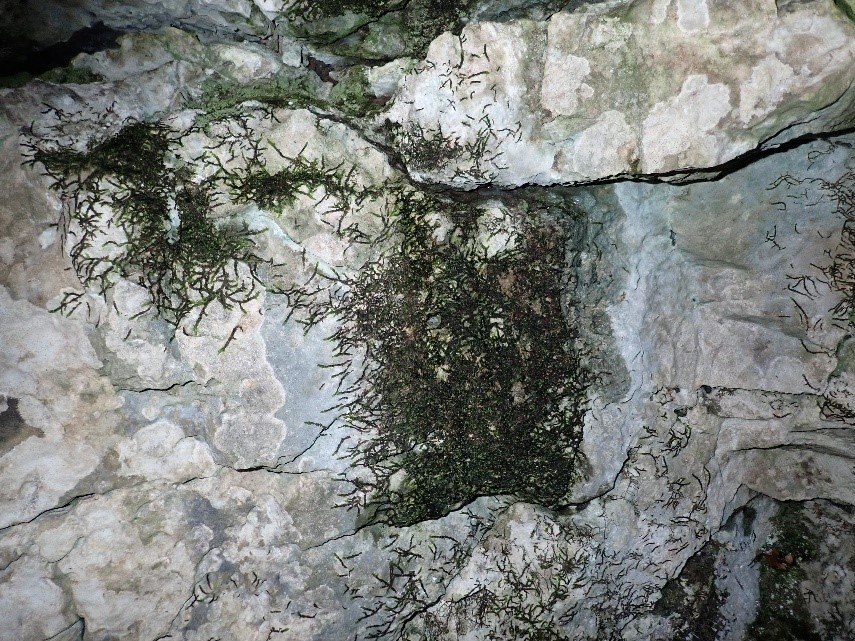

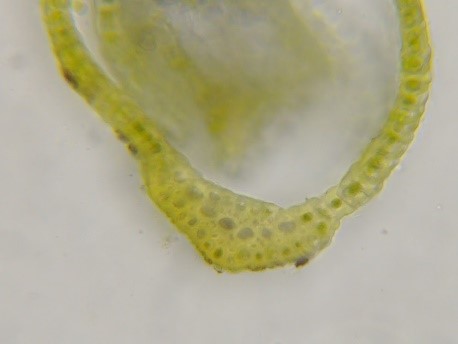

We parked in the big layby above the Tarn, just west of Little Asby, and started with a look at the remains of limestone pavement to the east of the layby. It was good to familiarise ourselves with some typical limestone species including Neckera crispa, Ctenidium molluscum, Grimmia pulvinata, Scapania aspera, Tortula muralis, Tortella tortuosa, Syntrichia montana, Hypnum lacunosum and Homalothecium sericeum. More surprising was Climacium dendroides, usually a species of damp places. David and Andy found some interesting wispy species, and consulting our field guides we decided they were likely to be Flexitrichum gracile and flexicaule (previously both in the Ditrichum genus). Both are lime-loving species and F. gracile is commonly found on limestone grassland, but F. flexicaule is much rarer and restricted mainly to limestone rocks. In this case it was distinctive, with many stiff, upright stems as shown in the field guide photos and described as ‘thin, deciduous branches with short leaves’. Microscope examination confirmed this ID, with the F. flexicaule shoots showing relatively short leaves on the longer shoots. Leaf sections ofthis species also showed a more abrupt transition between the leaf lamina and the costa compared to F. gracile, where you can’t see a clear ‘edge’ to the costa.

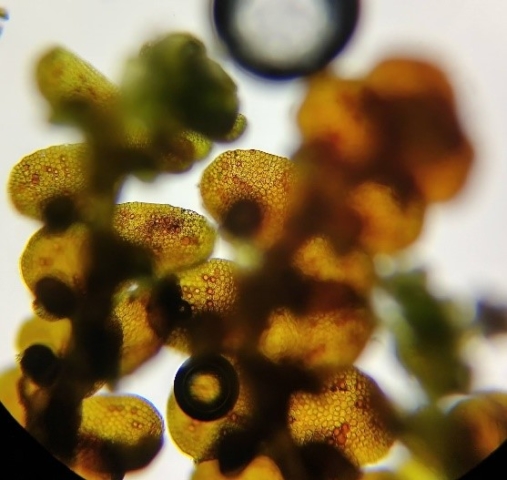

Once we felt we’d seen most of the species we were likely to find here, we drove down to the tarn and went to investigate the boggy area west of the road and down to Tarn Sike. The ground was not exactly boggy, but still damp enough for the bryophytes to be holding on. There were a few Sphagnum species (S. capillifolium, S. subnitens, S. palustre), also Breutelia chrysocoma, Aneura pinguis, Palustriella commutata and falcata, Scorpidium scorpioides and cossonii, Aulacomium palustre. There was a tiny rivulet of still-running water where we were pleased to spot Calliergon gigantea in several patches. There were extensive patches of a blackish Jungermannia liverwort, probably J. atrovirens or pumila, but impossible to definitively identify without perianths. J atrovirens according to the field guide is most common in limestone districts, but both are sometimes found together.

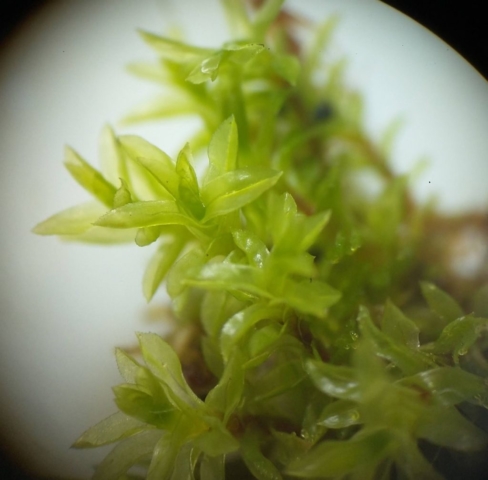

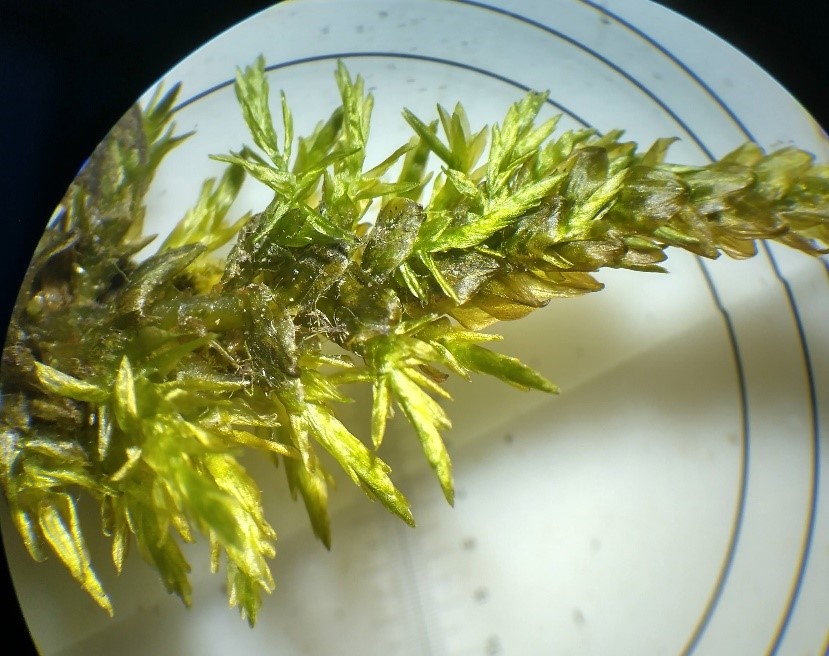

We made our way down to the road, passing some lovely autumn gentian, and from there down to the tarn, where we enjoyed the cool shade of a few trees. There were a few epiphytes there: Ulota phylantha, Ulota crispa, Frullania dilatata, Metzgeria fruticulosa, and a spectacular, very large Puss moth caterpillar spotted by Kerry. At the edge of the tarn was some Fontinalis antipyretica. By now it was about 2 o’clock and getting seriously hot, so we agreed to call it a day and headed back towards the cars. But we were soon distracted by a large boggy area with more Palustriella commutata and cushions of Philonotis fontana, where we were also excited to find some really good areas of Philonotis calcarea. There were actually several patches, looking really healthy and very distinctively curved to one side.

So all in all, it was a surprisingly good day and we were very happy with the interesting finds, though the species list is likely to be quite limited.

Text and photos: Clare Shaw