I’d not heard of Helbeck Wood until recently, though I knew the silhouette of Fox Tower and the haze of trees beneath it from journeys over the A66. The SSSI citation describes it as “considered by some to be the best ash-elm wood left on limestone in England”. Access has always been difficult or strictly limited, and yet it stands out on the species maps as one of only 4 grid squares in Westmorland with over 140 species found (most of the records date from the 1970s). One member of the CLBG knows the family who own it, so we had a way in…

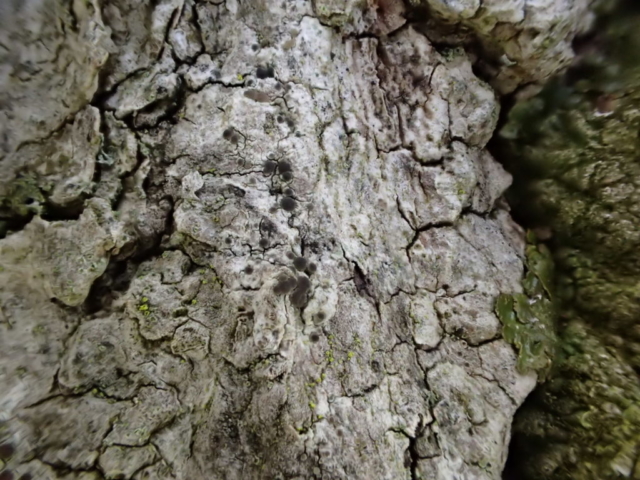

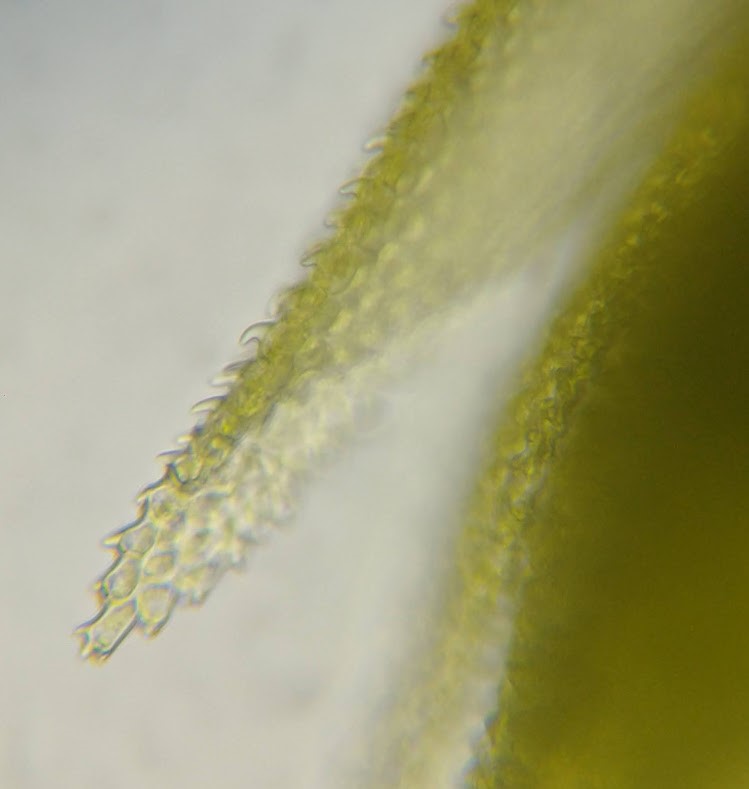

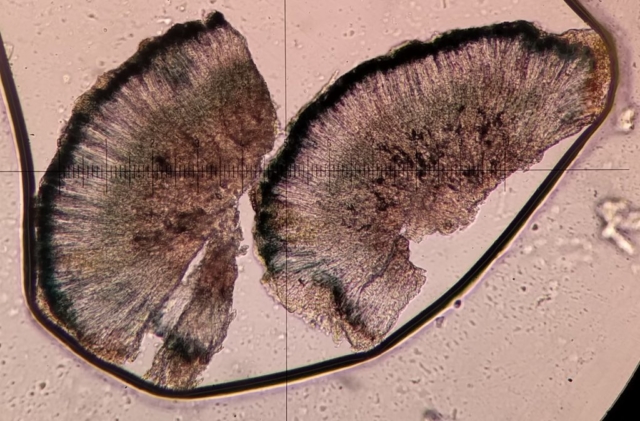

… but first I had to do a reconnaissance (health and safety you know). I had a grid reference on the GPS for Lobaria pulmonaria found in 2015, and headed for that. I followed the one track through thick woodland; lots of young ash trees; drifts of bluebells and ramsons. It was too dark for much lichen growth on the young trees, but the bigger, older ones had lots of Thelotrema lepadinum which seemed promising. The path narrowed, led to a mire and stopped. Machine guns rattled on the military range next door. The bearing led me up onto a block scree studded with flowers: woodruff, early purple orchids and hairy rock cress stand out in the memory. I never made it to the grid reference. Because before I got there I found 3 other trees with Lobaria pulmonaria and one with Nephroma laevigatum. A pied flycatcher lured me up to an easier return route via another Lobaria tree. Things augured well for the proper group trip.

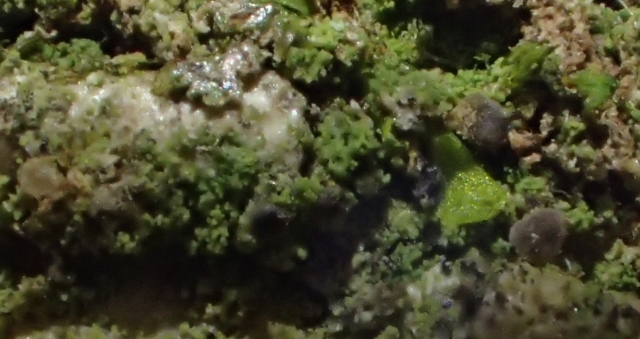

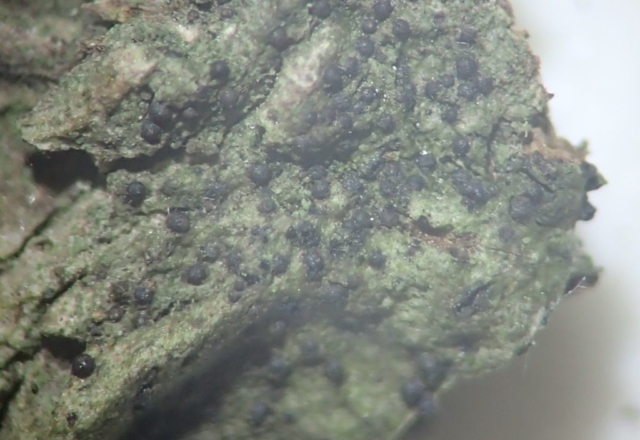

And so it was that eight of us formed the lichen party on a dry and sunny – if cool – morning. We moved more slowly through the lower woods: there was lots of regeneration, even if much of it was ash and suffering from obvious dieback. We found lots of Thelotrema lepadinum (again), and more Cliostomum griffithii than I’m used to, together with the usual Cumbrian woodland species. A young waxy thallus caused some confusion – but turned out to be Pyrenula chlorospila. We don’t see a lot of Pyrenulas. A green isidiate species is thought to be Bacidina sulphurella, or modesta as it has been renamed. There was plentiful Lecanactis abietina on the drier side of trees. Normandina pulchella was found growing on the same piece of liverwort as Micarea lignaria. The flowers were a frequent distraction. Today’s artillery sound was a series of deep “crumps”.

Slowly, we moved uphill from bluebell patch to bluebell patch. And then came out into more open rocky terrain and sunshine. The first Lobaria pulmonaria tree was found: Peltigera horizontalis and Bilimbia sabuletorum kept it company. Together with a lovely clump of wood sorrel. The more open landscape gave some limestone species, and then the party split: some went in search of more Lobaria, some returned the easier way.

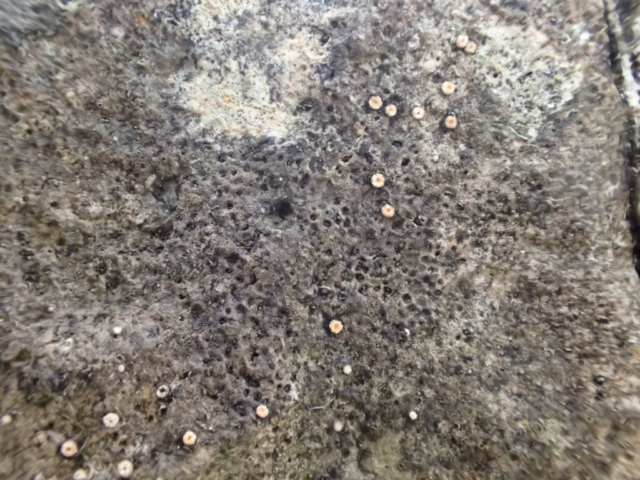

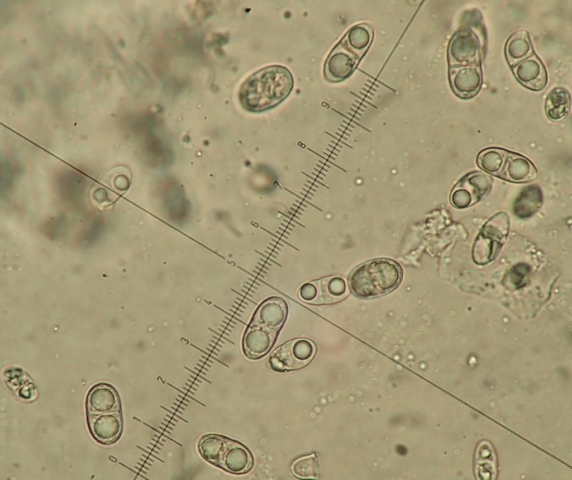

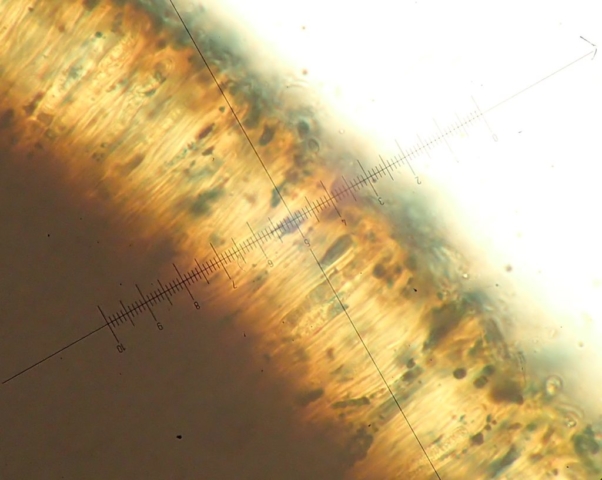

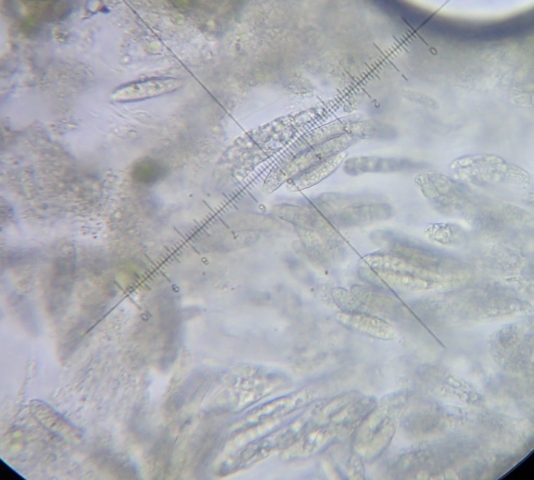

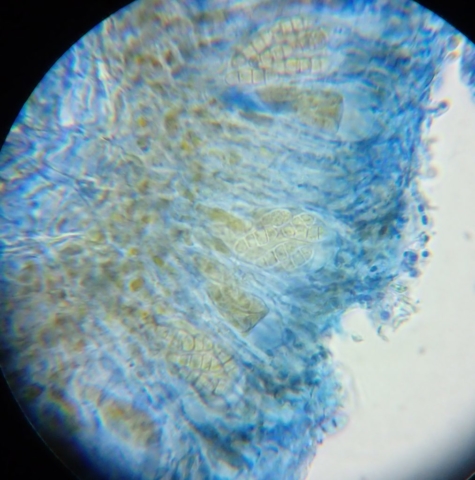

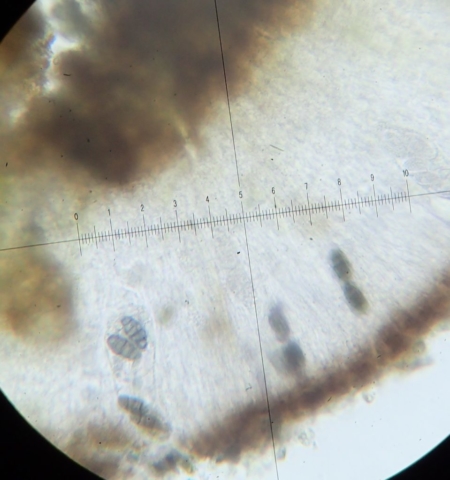

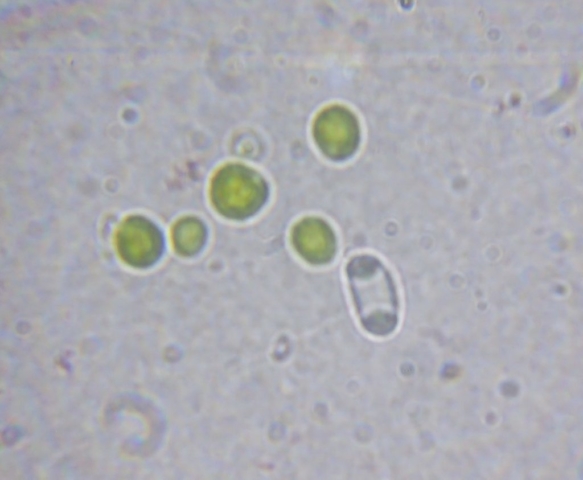

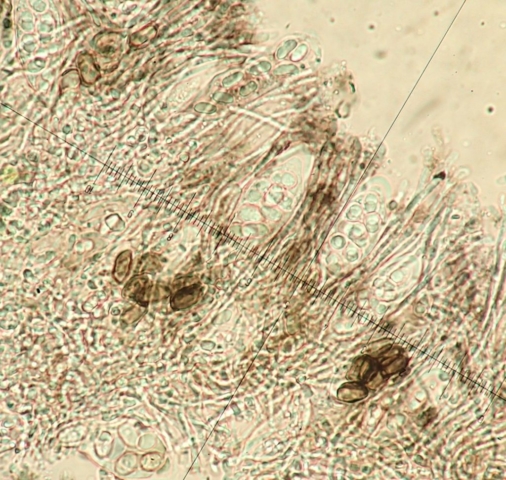

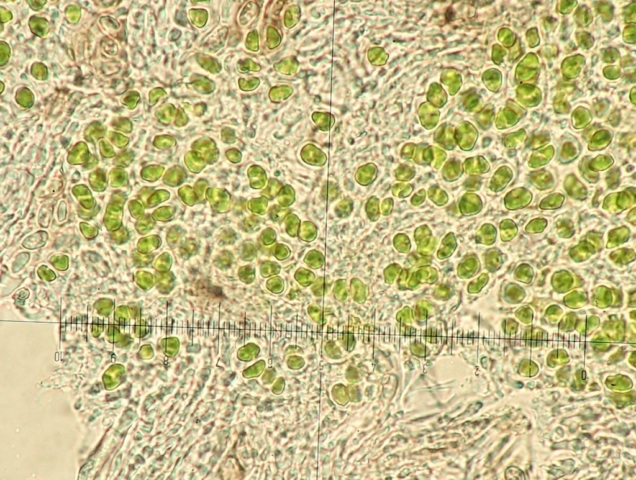

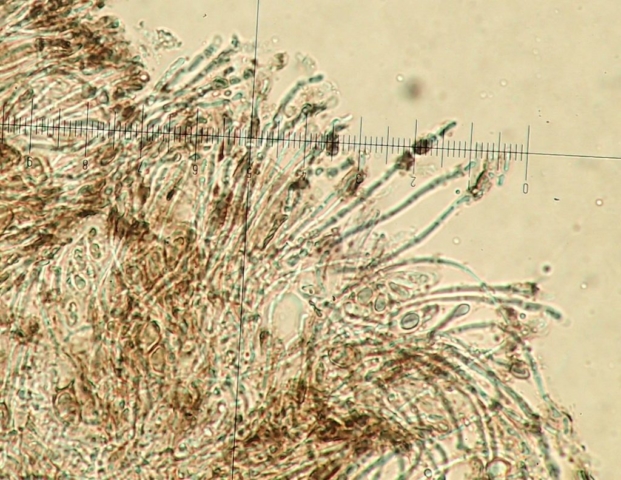

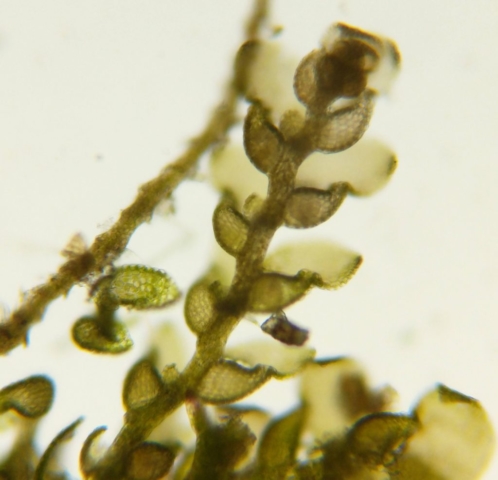

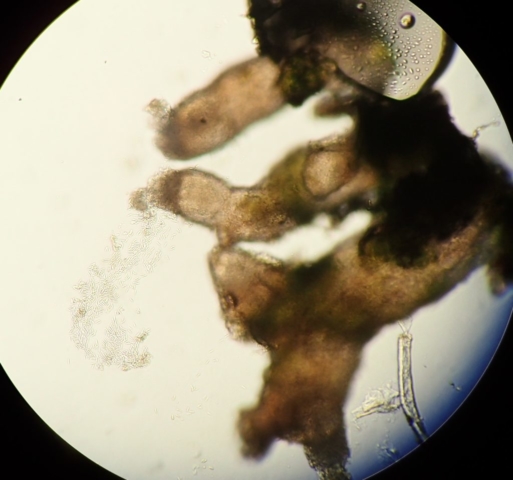

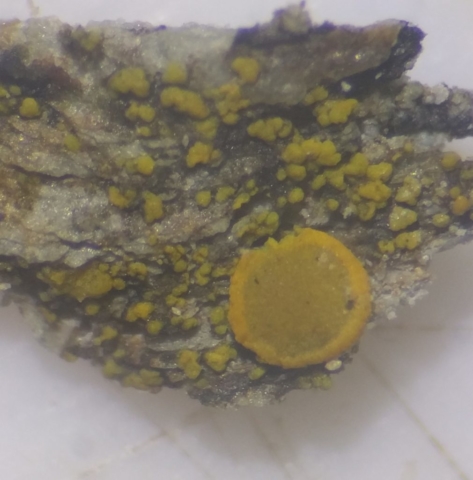

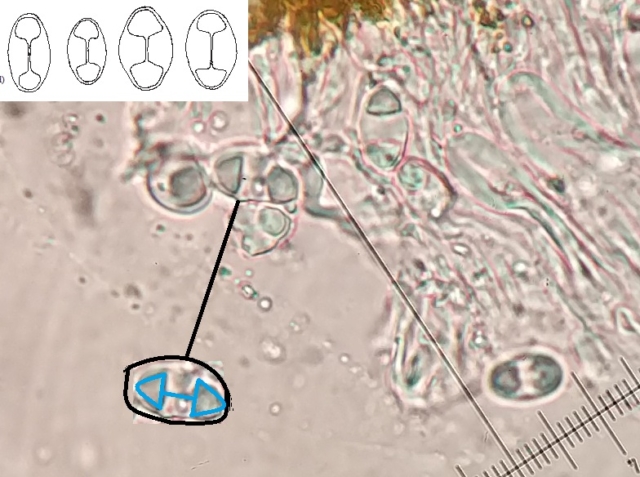

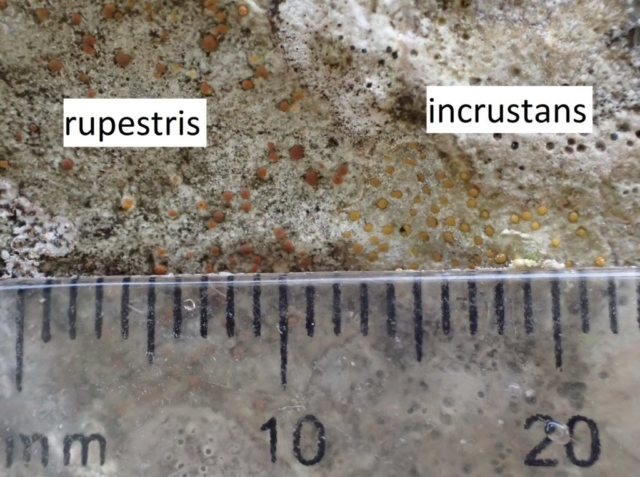

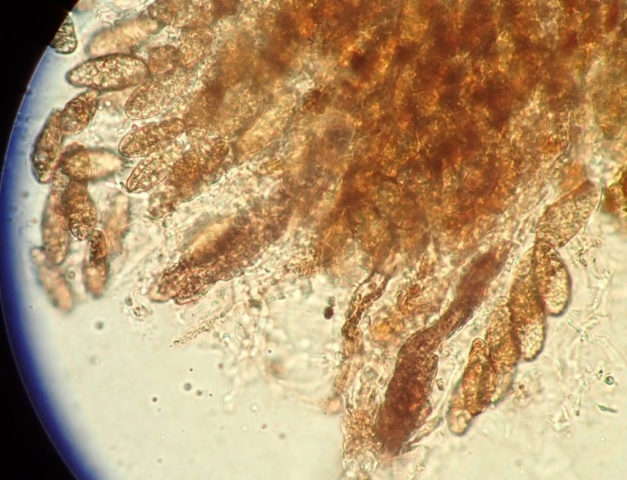

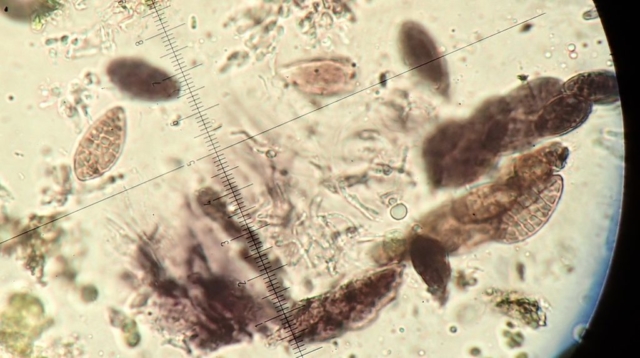

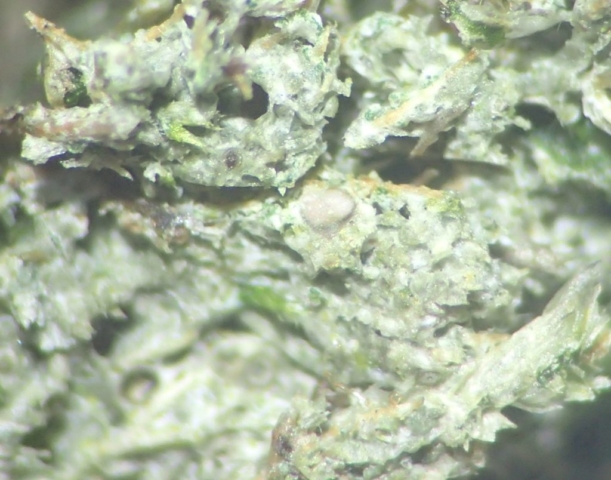

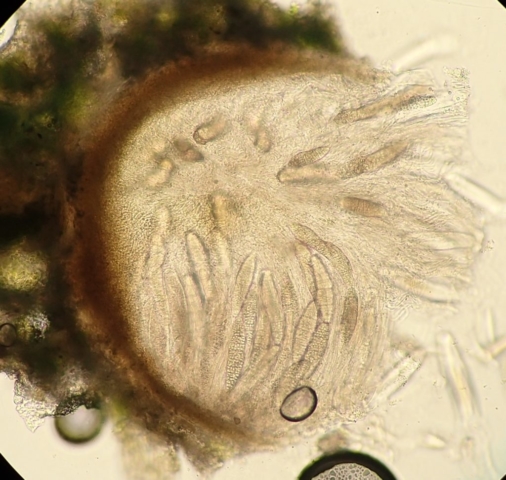

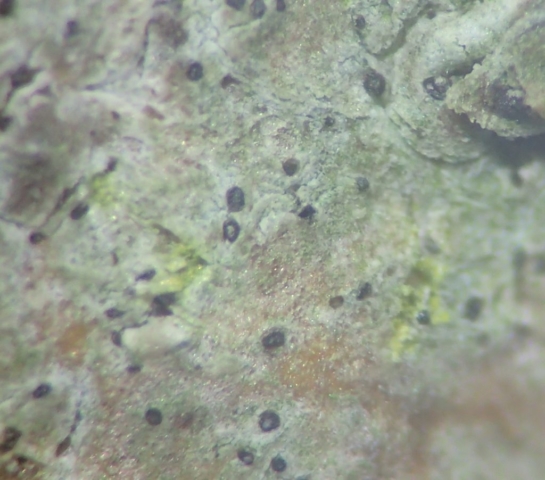

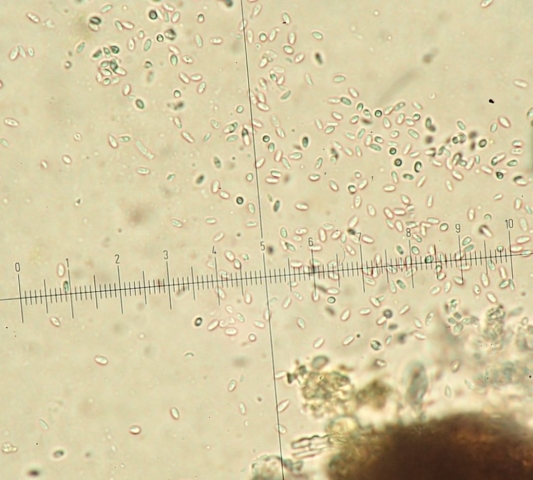

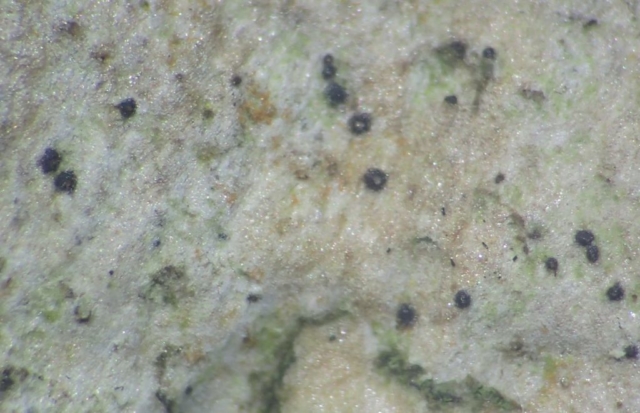

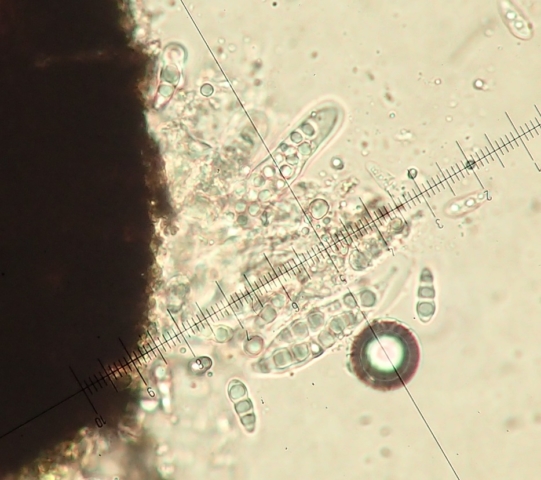

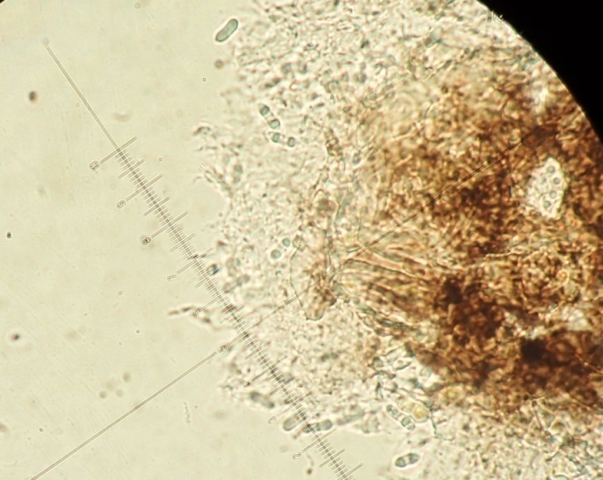

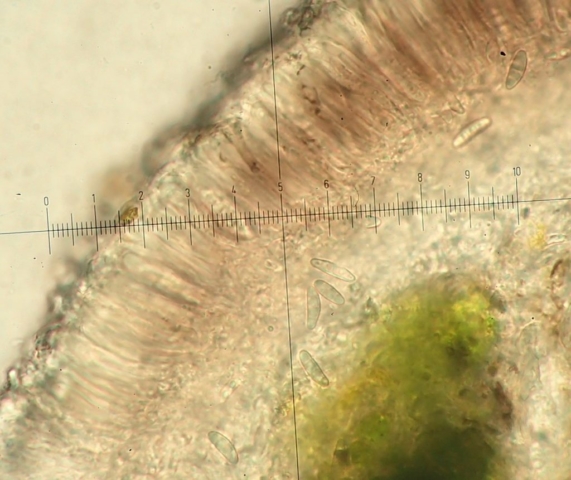

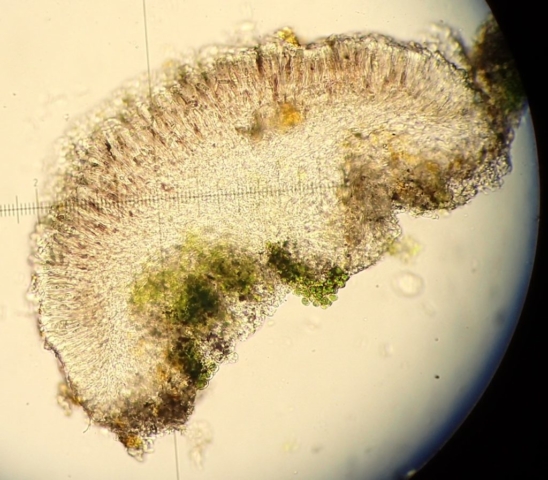

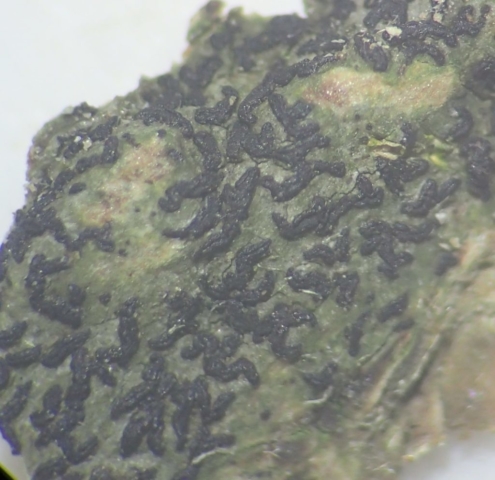

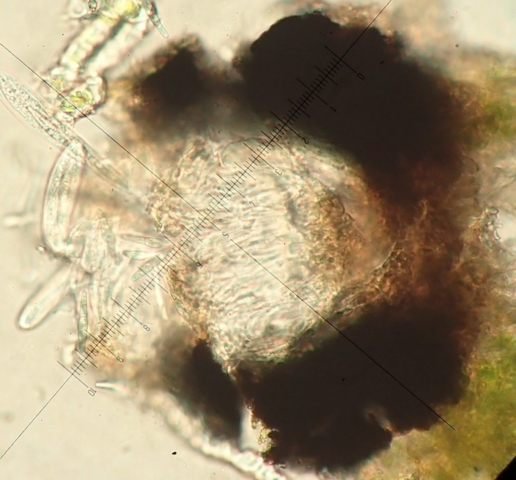

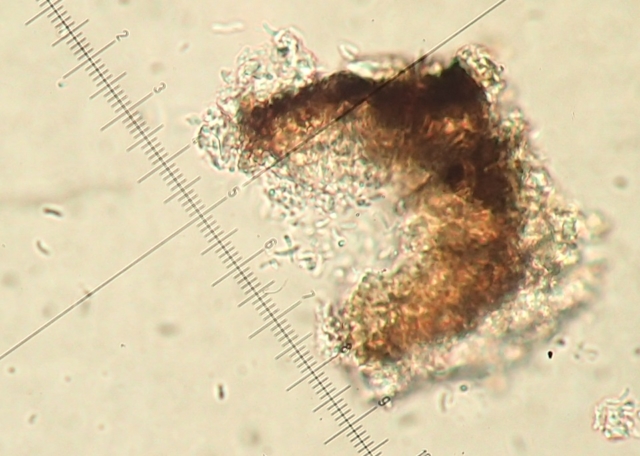

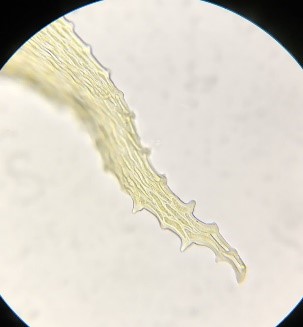

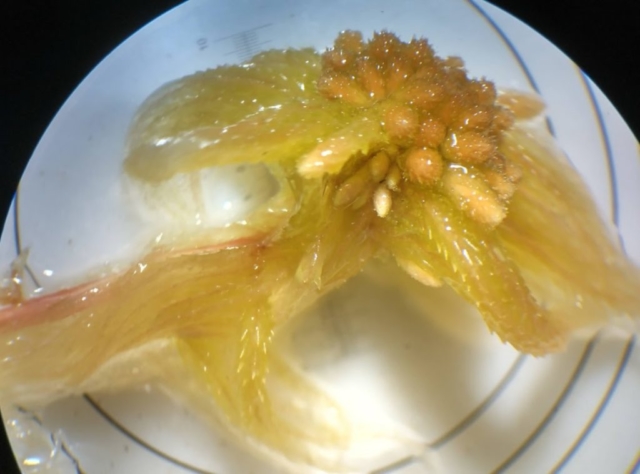

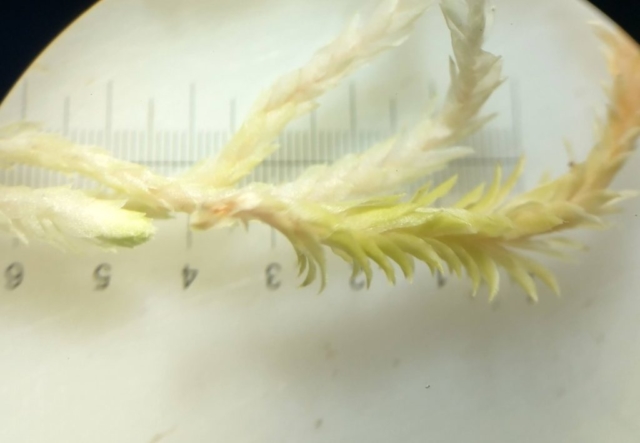

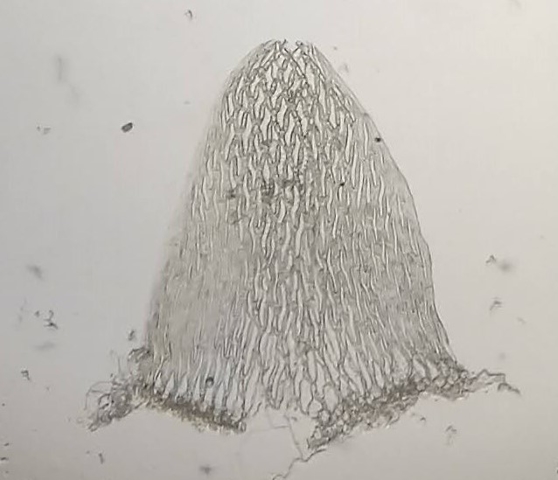

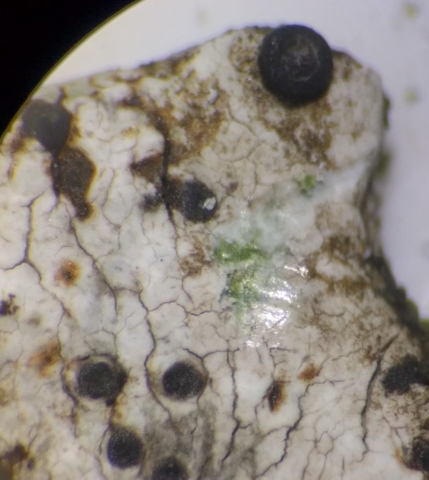

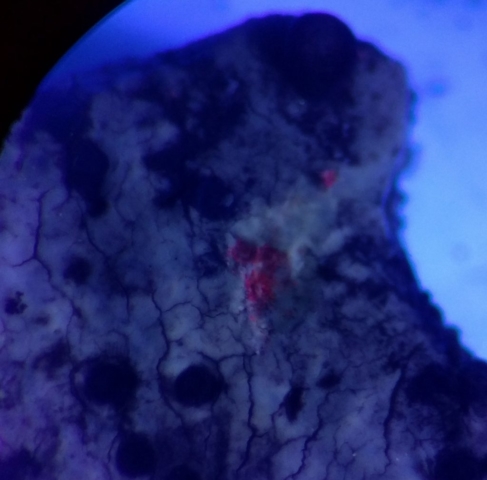

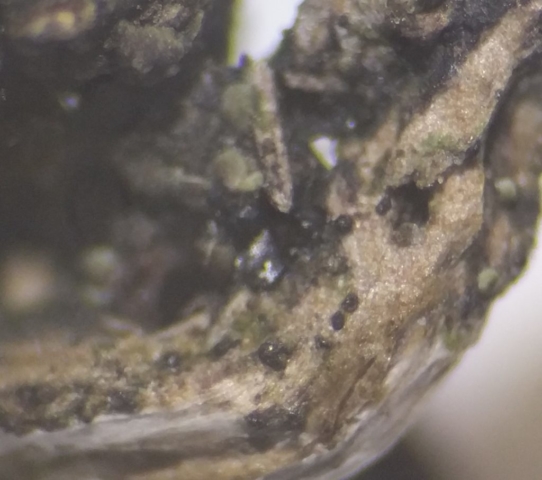

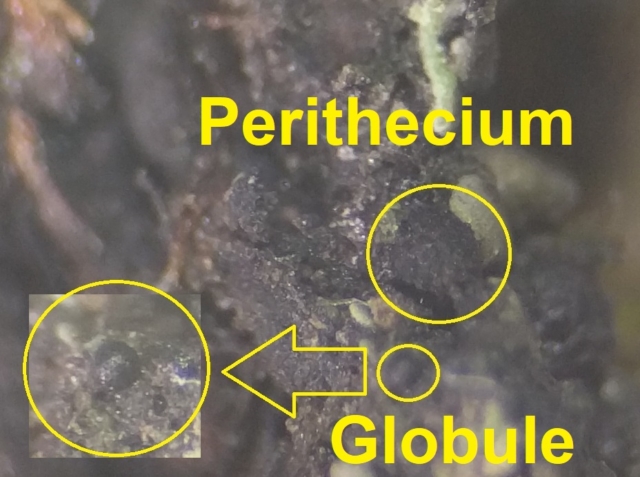

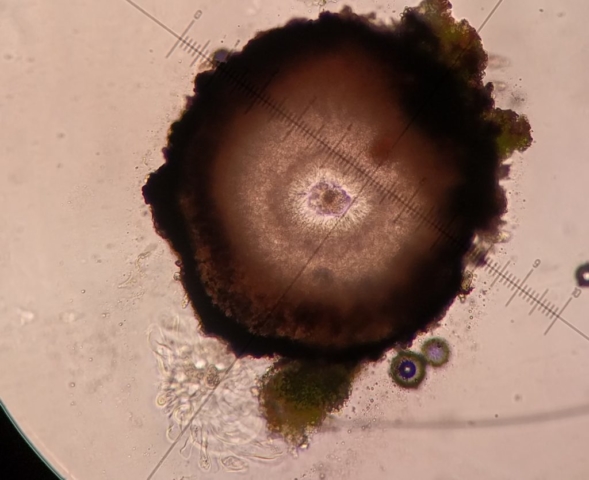

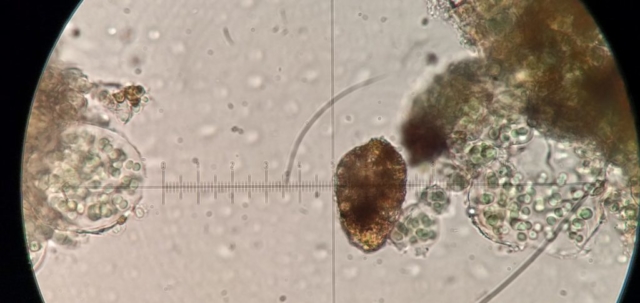

The Lobaria party report that the steep upper slopes of the wood show the underlying limestone with many small outcrops. In one area, semi-vegetated scree, consisting of smaller loose rocks, changes to a jumble of huge blocks each the size of a van, presumably left by the action of ice on the limestone scar above. Deep shaded cavities between these boulders provide a damp mossy habitat. Thalli of Dermatocarpon miniatum 5+cm across were widespread growing directly on the rock, along with Caloplaca xantholyta, Lepraria nivalis and many jelly lichens. Here, there are scattered ancient ash trees, appearing significantly older than any seen lower down. We were heading to a good grid reference for an ash supporting Lobaria pulmonaria, reported in 2015. One tree at that location had split, with half now fallen, still with some L. pulmonaria on the bark. However the standing part had a larger patch. A healthy colony of Nephroma laevigatum was on an adjacent tree. Within 10m or so we found a total of five ash trees with L pulmonaria, four of which had not been previously reported, with a small amount fertile (not common in Cumbria). Also on ash in the vicinity were two instances of Mycobilimbia pilularis (pinky-brown convex fruit on a green-grey thallus) and Gyalecta flotowii (tiny semi-immersed pale orange discs with a thick margin) which was confirmed later by examining spores microscopically. One smooth-barked young ash had Pyrenula chlorospila (also seen lower in the wood), not common in Cumbria though more frequent in southern England, with a waxy pale brown-orange thallus and very small perithecia. This specimen also had an outer ring of pycnidia (minute dots where asexual spores are made) which are not mentioned in the literature for P chlorospila, though common in other Pyrenula species.

The “easy route” party found Strigula taylorii on Sycamore in the darker part of the wood, Normandina pulchella growing on Parmelia saxatilis, and picked up some species in the parkland trees. As a final shot, Diploicia canescens was found growing on an oak tree just by the hall. Whilst not a rare species, I’ve not sure I’ve seen it growing on trees in Cumbria before.

We made over 140 records, including I think over 15 new species for the site. And it felt as though there was plenty more ground to be explored. A big thank you to the owners for letting us visit. A concern, obviously, is that most of the rarer species are on ash trees. So far, the older ones seem to be surviving in the face of dieback, but it remains to be seen what the next few years will bring to this remarkable place.

Pete Martin and Caz Walker

Photos by Pete Martin and Chris Cant